What would Charles Monroe Sheldon do?

For anyone born before the 1990s, What Would Jesus Do, or WWJD, recalls a brief boom of bracelets and other accessories; for those born after, it likely registers as some widespread cultural artifact from a vague past. The WWJD format is by now so ubiquitous it’s taken on countless variations, including mugs on which the face of Gibbs from the television show NCIS replaces the J.

The origin of this phrase in the American consciousness begins in Topeka, Kansas, with the pastor of that city’s Central Congregational Church, Charles Monroe Sheldon, class of ’83—1883, that is. Sheldon arrived at Brown two years after Inman Page, the University’s first African American graduate of Brown, had received his degree. The University was still several years away from creating what would become Pembroke College, let alone fully integrating the student body.

Sheldon went on to write In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do?, a book whose expression of progressive values, love for humanity, and distaste for hypocrisy seems completely on point for 2018. Since its publication in 1896, it has sold more than 30 million copies. Sheldon’s impact on the United States and, indeed, the world goes beyond a simple phrase emblazoned on wristbands no one wears anymore. After graduation Sheldon made his way to Vermont before settling in Kansas, where he preached at the church founded by his wife’s parents.

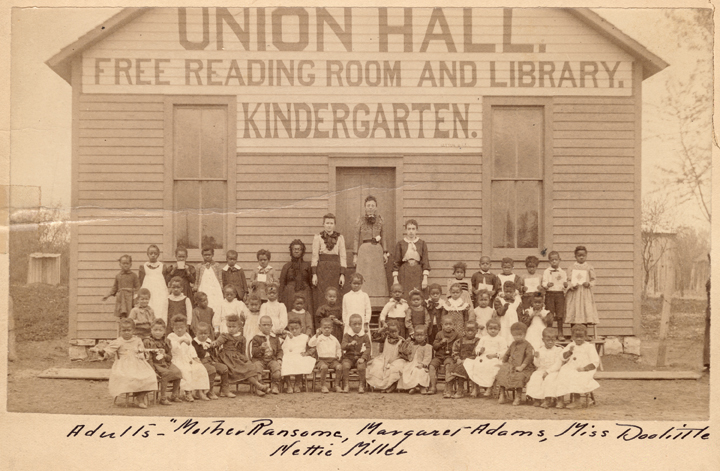

The sermons he gave became his book. According to the Kansas Historical Society, the sermons were more like radio serials, fictional accounts meant to keep the congregants coming back, complete with cliffhanger endings. Beyond asking others what Jesus would do in certain situations, Sheldon was determined to do good on his own. The Tennessee Town Neighborhood Improvement Association described him as “the first white man to show any real interest in Tennessee Town,” the small community of African Americans that had been routinely ignored by the city of Topeka. Sheldon helped the neighborhood set up its first kindergarten, which happened to be the first black kindergarten in the American West.

The Kansas Shawnee County Parks and Recreation Foundation is currently attempting to preserve Sheldon’s home and study, where he penned his sermons. You can check out their campaign at www.sheldonslegacylives.com.