Reader comments since the last issue:

Where Food Comes FromI was thrilled to see the cover story on the exemplary work of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Sadly, though, worker injustice is not limited to either tomatoes or Florida. In the last year or two alone, major newspapers have highlighted poor conditions of myriad sorts on Mexican farms, slavery on fishing boats, child slavery in cocoa farms, and continuing dangers for apparel workers two years after the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh—all of whose products end up in U.S. stores.

I cannot implore my fellow Brown alums enough to consider the conditions under which their food and clothing are produced, and buy with these conditions in mind. The easiest way is to look for certification labels: Fair Food is one; Fair Trade USA is another and extends to coffee, cocoa, tea, a variety of produce, coconut, fish, apparel, and other categories. (Full disclosure: I just finished a fifteen-month stint working at Fair Trade USA, but I am not speaking on behalf of that organization). Even better is to ask your stores to stock more of these products. While the market for ethically sourced products has grown significantly, it is still a minuscule percentage of the total. Can we, as consumers, leave a better legacy than that?

Let’s use our power as consumers to say no to these abuses.

Lee Anne Snedeker ’85

San Francisco

lasnedeker@hotmail.com

I am so appreciative that the BAM recognized the inspiring and tenacious work of Greg Asbed ’85 and Laura Germino ’84 in “Justice in the Fields.” Their leadership as two of the organizers of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), as two of the architects of its effective strategies for galvanizing consumers for improving conditions for farm workers, highlights the long way we still have to go to treat these workers with the respect—and compensation—that they deserve.

It is worth pointing out that the strategies the CIW employs are similar to those of another farm worker organizing effort, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), founded by its president, Baldemar Velasquez, in Ohio in 1967. Among the FLOC’s achievements is a February 1986 precedent-setting three-way collective bargaining agreement among FLOC, growers, and Campbell Soup that provided wage increases, grievance resolution, health insurance, and committees to study pesticide safety, housing, health care, and day care issues. For the past eleven years, despite meager funding, FLOC has been challenging RJ Reynolds and the other major tobacco companies to demand changes in the tobacco fields. With the support of consumers, the general public, and faith communities, I believe that RJR will soon become a part of the solution.

W. David Austin

Durham, N.C.

daustin@mindspring.com

The writer is a Brown parent.

Supporting Undergrads

We read with great interest your essay “Opening the Gates” about Brown’s efforts to increase access for students from less privileged backgrounds (Here & Now, November/December). As former student activists for need-blind admissions and cofounders of the group Students on Financial Aid (SOFA), we are pleased to see Brown’s leadership on this issue.

We also are impressed with the work of current students, such as Manuel Contreras ’16, who have shined a light on the challenges faced by first-generation college goers and students from families of lower socioeconomic status. In support of President Paxson’s commitment to making undergraduate financial aid one of the pillars of the BrownTogether fund-raising campaign, we have decided to double our customary annual contribution. We hope that those who share our belief that a Brown education should be open to every deserving student will join us.

Michael Householder ’89, ’90 MAT

Suzanne Rivera ’91

Cleveland Heights, Ohio

smr140@case.edu

householder.michael@gmail.com

I had always made it a point to meet the holders of the chair endowed by an alumnus in honor of my late dad, Israel J. Kapstein, and as a result Professor of Literary Arts C.D. Wright and I became friends (see “One Big Self,” Obituaries page 68). We exchanged lengthy letters about once a year. She was a great and stirring poet, a fine person, a warm teacher, and a lover of words, of students, of family, of people, of the world—not in any order, but all at once. Brown and all of us are lessened by her passing.

Jonathan Kapstein ’61

Brussels, Belgium

Poet and Teacher

C.D. Wright is the most remarkable voice of her generation, devoted to understanding and recovering the layers of histories buried beneath the soils of the South along the Mississippi River—an understanding that helps us all to uncover the multilingual, multivocal, multicultural, and multiracial intertwinings and bindings that characterized the South from its beginnings. I was privileged to talk with her in 1985 as a PhD applicant.

In some ways I still see her walking on the banks of the Mississippi River. Her youthfulness made me feel that she was going to write for another fifty years and take us to many more places than we could imagine. It is a sad truth that we canonize our poets once they are memorials for us rather than while they are living alongside of us. Her vision places her alongside Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, Langston Hughes, and Adrienne Rich.

My condolences to her husband, Forrest Gander, to their son, and to others in their inner circle.

Camille Roman ’90 PhD

Providence

The writer is co-editor of volume two of The New Anthology of American Poetry, published by Rutgers University Press.

I was moved and inspired reading about this luminous, courageous, and brilliant woman. What an incredible legacy she has left. I was especially touched by the story of V, and I can imagine the ardor with which Wright wrote One With Others. What a loss for all of us. Thank you for writing a piece that did her justice. She really left an indelible mark on the world.

Russella Serna ’89

Santa Fe, NM

Friend and Mentor

If you are fortunate, there are people in your life who have truly made a difference. I went to Brown in 1969 from what is now UMass Dartmouth to study with Professor of History Tom Gleason, and was one of his first graduate students.

I was unsure of myself, and he bolstered my confidence, became my mentor, encouraged me, was my advocate, and simply helped me look at the world and my future in a different light. We kept in contact for many years, but that faded until he tracked me down after my thirty-year government career to “catch up” and to tell me about his autobiography. It was as if time had stopped, as if we had seen each other yesterday.

Tom Gleason was one of a kind, a true scholar, an inspiring lecturer, a friend and mentor to many, and a classic example of what it means to be a decent and caring individual. I consider myself incredibly fortunate and blessed to be among those who have crossed his path.

Joseph W. Augustyn ’71 AM

Fairfax, Va.

Tom Gleason was an incredible human, kind, funny, all-knowing, and generous, and so important to so many in academia and beyond. I was lucky to be one of Tom’s first students at Brown when I enrolled in his inaugural lecture course on Russian history in the fall of 1968. Apparently, from anecdotes he told often and wrote about later, he was nervous to appear before the class and only relaxed when someone asked where he had acquired such a great map posted over the chalkboard.

To this directionless, unmotivated eighteen-year-old sophomore from sunny California, Tom appeared a master of his subject and the very ideal of the New England intelligentsia. He also had the magic that drew in an audience, a talent he still possessed when my daughter Liz Young ’13 took in his every word in several visits to the welcoming John Street home that he and his wife, Sarah, opened to hundreds of students over the decades.

Sincere condolences to Sarah and their children, Meg and Nick.

Connie Jo Dickerson ’71

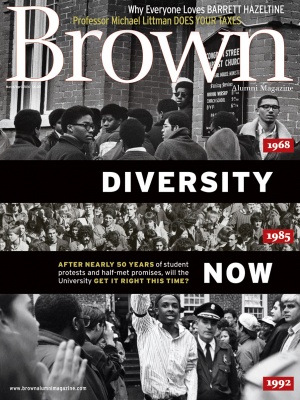

Is Brown Diverse Enough?

When I saw an article about diversity at Brown, I hoped I might read a celebration of Martin Luther King’s vision: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

I am disappointed if there are racist actions or remarks at Brown. However, to impose an ethnic or color test to ensure that there is representation of students or faculty proportional to the national population is also racist. Brown stands for excellence. Brown should admit or hire candidates of any background based on merit and character, not on skin color or ethnicity. As an aside, I wonder if there is diversity of political opinion in the Brown faculty. Perhaps it would help to have some political conservatives on campus to champion the individual liberties enshrined in the U.S. Constitution rather than group grievances.

Farrel I. Klein ’77

Providence

“Is Brown Doing Enough to Increase Campus Diversity?” asks the BAM on its January/February cover. In the previous issue, we alumni were informed that President Christina Paxson aims to preserve the previous administration’s successes while pushing Brown to be even more itself: more diverse, more rigorous, more interdisciplinary, more innovative, more highly esteemed.” That “diverse” should lead the list of goals is no longer something surprising. In the same issue, two articles about anti-black racism were offered: “Moral Outrage” and “A Call to Action.”

It is to be expected that young people will be caught up with their usual passion in campaigns that appeal to their sense of justice. But one might hope that the adults at the institution would bring some critical analysis to bear on the subject, rather than merely echoing the slogans of the day. BAM reports that “only 6.7 percent of current undergraduates are black, compared to 13.2 percent of the current U.S. population.” Should we take this as proof that Brown underestimates black applicants? Why does no one ask, for instance, what part of the black applicants score at Brown’s level on their SAT tests? And why do we never hear comparisons for other ethnic groups of their percentage of the student body in relation to their share of the U.S. population? All this diversity talk is ideological foaming at the mouth. It is perhaps excusable in young people, but when uttered by the president and other administrators, it becomes revolting.

Lawrence G. Proulx ’75

Cergy le Haut, France

I read your current issue with disgust.

I am appalled to see that Brown has gone back to the quota systems of the 1940s. Back then the quota system limited minority entry. Now the system, in response to the loudest voices, will favor minorities. The system should bring only the best and brightest and, if necessary, give financial aid to avoid losing those who are qualified for financial reasons only.

Jack Resnik ’61

Cayuga, N.Y.

I read with some dismay the article entitled “Keeping Brown Accountable.” I fail to understand why skin color/ethnic origin/sexual orientation/religious belief should become criteria for professor or student presence in any university community. Such quotas for “inclusion” based on demographic statistics are just the other side of quotas for “exclusion” and neither are appropriate in the modern world. Nor should the University waste its funds on even more committees and reports to analyze and respond to noisy but unspecific complaints by “activists” exploiting old slavery guilt. University time and money could be better spent on educational needs and goals, which in this article seem to be lost in the shuffle. Should Brown University change its name to Silly University?

Louise Rinck Roby ’65

Grenoble, France

louroby@orange.fr

The article about the protests over a lack of campus diversity fails to acknowledge some primary causes of this lack. Large numbers of children of color are born into impoverished single-parent homes in poor neighborhoods with few opportunities. These children don’t have access to preschool experiences. They go to failing schools and face neighborhood violence and dysfunction. It is wonderful that many are able to overcome these and other handicaps and end up at Brown. But until the majority of children of color have the same advantages that most white children have, there will be fewer who can meet the criteria for enrollment or for a faculty position at Brown. Dealing with the handicaps so many minority children face from birth should be a far more important focus of activists than perceived lack of diversity on campus.

Robert Follett ’50

Highlands Ranch, Colo.

Whenever I see another article in which Brown (or any other selective college or university, for that matter) trumpets it efforts and progress toward increased diversity, I am struck by one thing. For all the effort Brown has made throughout the many years, since long before my time, to become a national—and indeed a global—university, every entering undergraduate class is still dominated by kids from a few East Coast states, with a disproportionate number of those from elite private high schools. It strikes me that the same was true in my time, and it sends up a red flag that, I believe, the Brown community needs to address.

The reason for this imbalance reflects an assumption that is holding the University back and thwarting its full potential. While Brown has made great strides in increasing diversity, identifying and recruiting students with a wide range of talents and backgrounds, it has still not let go of its roots as a finishing school for children of very wealthy, influential, mainly East Coast families. The assumption that the long-term economic health of the school depends on the largesse of these families is, unfortunately, still at the heart of Brown undergraduate admissions, and that of all the Ivies and many other competitive private schools.

While the admissions process is, to some degree by necessity, cloaked in secrecy, I suspect that this reliance on wealthy families may be becoming even more pronounced, ironically due to the trend toward need-blind admissions and better recruitment of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. In tuition, the wealthy are subsidizing the education of the not-so-wealthy, which is not necessarily a bad thing, unless this fact distorts the admissions process in a way that produces a bimodal socioeconomic distribution in the student body. As universities do a better job of recruiting promising students of low income, the incentive has become greater to identify and cultivate families of great wealth to offset the perceived cost of diversity.

Brown should be the leader in instituting an undergraduate admissions policy that is wealth-blind as well as need-blind. We should eliminate all preferences in undergraduate admissions that skew toward the wealthy and powerful, including the preference for children of alumni. Students cannot be blamed for having wealthy or powerful parents any more than they should be shunned for having a disadvantaged background. This is not about class warfare, it is about acknowledging our assumptions and examining them in the light of day. The time has come to have this conversation openly as Brown looks to the future.

Guy Rosenthal ’80

Wheaton, Ill.

grosenth@prodigy.net

I have looked long and hard at the photograph on the table of contents page of the January/February 2016 issue. The eleven somber, hostile, angry faces we find in it give us one haunting view of what we have accomplished in our decades-long attempt at achieving diversity and inclusion at Brown. I cannot remember having seen a more depressing picture of students on our campus. These people are unhappy at Brown. One response is to give in to their demands (for some of which see “Do Better,” Elms, January/February). Another is to suggest that they transfer to schools at which they can acquire the education they want, help them depart, and fill the places they have left with students who want to study on this campus.

David Josephson

Providence

david_josephson@brown.edu

The writer is a Brown professor of music.

As president of Pembroke’s Student Government Association (SGA) fifty years ago, I was no stranger to student protests, so I read with interest “Keeping Brown Accountable.” I noticed a lot of statistics about racial and cultural diversity, but virtually no data was presented on the vastly more important issue of intellectual diversity, the promotion of which is at the heart of the mission of any college or university. For example, what percentage of administrators and faculty have experience in business, or believe climate science is not quite “settled,” or are veterans of military service?

The narrow definition of “diversity” as racial or cultural is not unique to Brown. The modern university has become preoccupied with racial and cultural identity and sexual liberty. This is so pervasive that many issues that should be the center of intellectually rigorous debate in our universities are invisible or are too controversial even to bring up. Where is the leadership from Brown’s administration and faculty to push back and challenge students to go beyond their “comfort zone”? Where also are the percentage goals for recruiting more intellectually diverse faculty to redress the current dangerous imbalance of diversity of thought?

Carol Dannenberg Frenier ’66

Chelsea, Vt.

cfrenier@myfairpoint.net

I was struck by the claim that, even if the proportion of faculty from underrepresented groups was doubled, it would still be “far short of the percentage of racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. population.”

But why is this metric at all relevant? The conventional argument for diversity is that different groups have different perspectives— in itself a somewhat dubious and implicitly racist argument. The “activist” argument seems to go beyond this and to claim that the ideal situation would be one in which the faculty mirrored the nation. Consider the implications. Is there a black or Hispanic perspective in physics and chemistry? In the social sciences, race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation probably correlate somewhat with an individual’s views, but the whole idea of science is that the scientific process in itself is corrective of any personal bias. Indeed white Americans themselves are diverse in their ethnicity and opinions.

The idea that students should be taught by professors who look like them is obscene. Instead, let Brown hire faculty based upon intellectual and academic merit, regardless of race, gender, or national origin.

Christopher Hewitt ’72 PhD

Glen Echo, Md.

hewitt@umbc.edu

Waiting List Blues

I read, with dismay and incredulity, the comments by Dean of Admission James Miller ’73 in the article “Saying Yes”. Specifically, the comment “it’s unclear what’s behind the rise” (of admitting 196 students from the waiting list, up from 42 last year and just two from the year before).

The truly troubling issue here is that fewer accepted students are choosing to attend Brown. It is a development that Dean Miller and his staff should undertake to answer. It might be answered by a simple follow-up survey directed to those accepted who chose not to attend. The survey might also ask what college the accepted/not attending students chose to attend; if none, then why are they not attending college, and what are they doing now?

Eugene D. Newman ’67

Sunny Isles Beach, Fla.

edncpw@gmail.com

A Change of Course

I was saddened to read about the passing of former urban studies professor Mel Feldman ’45 in the November/December Obituaries. His inspiration led to my enjoyable and successful career in planning. I entered Brown as a math whiz soon to be completely flummoxed by linear algebra (couldn’t grasp n-space). Maybe because I created play towns as a kid, I was attracted to Mel’s Special Topics course on urban renewal. Not only did the subject matter interest me, but I first became aware that there was a profession of city planners. My contact with him led to an independent concentration in urban studies and then a graduate planning degree. I’ll always remain grateful to Mel.

Rick Hyman ’73

Santa Cruz, Calif.

A Fine Teacher

I am sad reading of our loss of theater arts professor John Lucas in the January/February Obituaries. While he took very seriously the department’s productions, I found him on a personal level to be among the most lighthearted faculty members I met at Brown. He was also a fine teacher. That’s about all one can ask for as an undergraduate.

Tracy Baer ’77

Los Angeles

Teacher

Thanks for recognizing the induction of Fritz Pollard ’19 into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame. He was the first black to play in that annual classic, but he was not the first of his race to play football at Brown. That distinction belonged to Edward D. Stewart, a backup center on the 1894 varsity team.

Peter Mackie ’59

Lexington, Mass.

petermackie@verizon.net