In the summer of 2006, Brown officials received an unusual handwritten note. In bright, bold handwriting, Goldie Corash Michelson wrote that she was from the class of 1924 and wanted to know: “Am I the oldest living alumna?” Then she added: “JUST CURIOUS!”

Michelson was a feisty, generous woman with a warm twinkle in her eyes. Her greatest loves included her family and theater, and she was well known for her community activism. Beyond her own remarkable story, Michelson was also the University’s last living link to the 1920s. Her life spanned almost half the entire history of Brown; she lived through eleven of its nineteen presidents. Her time on campus opened a window onto a fascinating, significant period in Brown’s history, a time when it was recovering from the trauma of World War I. It was an era when women were still pioneers in collegiate education, when an early group of immigrant and Jewish students like Michelson could at last be found on campus, and when the twenties began to roar.

Born in Russia in 1902, Michelson arrived in Worcester with her family two years later and spent almost all of the next 112 years in that city—except for four years, 1920 to 1924, when she lived at the Women’s College of Brown University. In perhaps an indication of uneasiness with the whole idea of women at Brown, this was the third name for the college since 1891, the year the first six women were admitted, first to the awkward-sounding Women’s College Adjunct to Brown University and then to the Women’s College in Connection with Brown University. Only in 1928 would it settle on its final name, Pembroke College.

When Michelson entered in 1920 along with eighty-one female classmates, the history of women at Brown was still less than thirty years old. Tuition was $200 a year; fees ran about $600, no small sum at the time. (It was also in 1920 that Brown’s annual budget reached $500,000 for the first time; it’s now $1 billion.) Brown’s model for admitting women was coordinate education, which was, essentially, separate but equal. After all, many men at the time were militant in their opposition to full-fledged coeducation—in June 1922, the Brown Daily Herald published an editorial about “The Pembroke Problem,” which argued that any steps toward coeducation would weaken Brown.

Nevertheless, the faculty of the women’s college grew, slowly at first, and introductory course offerings were similar at both colleges. Women attending class with men “on the hill” were extremely rare. Single-sex classes, in fact, would continue into the 1940s. The library in Pembroke Hall steadily improved while Michelson was at Brown, but its holdings were dwarfed by the John Hay, the campus’s main library, which had opened in 1910. It’s no surprise that most women used the John Hay not only for its superior research materials but also as a place to meet male students—even though men and women sat at separate tables.

Only a few years before Michelson, women routinely had chaperones when they visited the men’s campus, and some were too intimidated to go. Although Michelson had a somewhat bumpy first two years academically, after she discovered the social sciences that would be her lifetime interest she came into her own. As she received special permission to take upper-level classes with men, she spent more time on the men’s campus completing courses that, a decade later, would lead her to a master’s in sociology from Clark University.

But that was well into the future. For Michelson and many classmates there were endless discussions about a relatively new subject: what women would do post-college. Many women, of course, would still not end up working outside the home. They eagerly anticipated a future reflected in the Rhode Island Hospital Trust ad that appeared in their Brun Mael (“Brown Legends”) yearbook: “The college women will find the practice of maintaining a bank account and paying all bills by check both a present convenience and an asset in the future profession of home management.”

Yet the early twenties were also a time when at least some women were thinking about careers outside the home. Michelson’s classmate Hilda Marion Hoffman, for example, became a bank vice president and later wrote in a thirty-fifth-reunion questionnaire: “Had I gone to College in 1916 when I graduated from high school, no doubt I would have prepared myself to be a high school teacher. . . . Who could have told then that when I was to go to college in 1921 new fields, undreamed of at the earlier date, would have opened for women?”

Campus life for women, however, was still full of teas and dances, with intricate decorations, food, and fashion. Just before Christmas 1923 at a house dance in Miller Hall, where Michelson lived, the menu included pistachio and raspberry ices, tiny cream puffs, and lady fingers with green and red icing. The Pembroke Record, the student newspaper, called it a “brilliant social success.” Michelson once told her daughter, Renee Minsky, that when she first arrived on campus with her mother, she saw “a group of girls and boys talking” and told her mother, “Okay, you can go now.” Later, Michelson was proud to have a Brown boyfriend.Brown in the early 1920s was still emerging from the shadow of World War I. Thousands attended the April 6, 1921, ceremony dedicating Soldier’s Arch on Thayer Street, which honored the forty-two alumni, students, and faculty who had died during the war. A few months later, on November 13, as thousands of students, ex-servicemen, and others watched, Brown awarded an honorary degree to Marshal Foch of France, who had been the Supreme Allied Commander. The “Marseillaise” was played and, according to the Brown Daily Herald, the crowd was the largest ever assembled on campus. In his remarks, President Faunce likened the visit to that of George Washington in 1790.

The buildings around the College Green in 1924 would be familiar to a visitor today, but the Pembroke campus had only four of any size. The first, Pembroke Hall, had been dedicated in 1897 with a speech by Sarah Doyle, an advocate of women’s education in Rhode Island who died in 1922, while Michelson was at Brown. Sayles Gymnasium (now Smith-Buonanno Hall) was used for physical education classes and also had a “resting room,” where women could sit and have tea. Michelson was an early resident of Miller Hall, built in 1910 as the first dorm on the Pembroke campus. Residents would sing such songs as “You’ve Got to Kiss Mama” and “Louisville Lou” to women across the way in Metcalf, which had opened in 1919. Michelson and her classmates were part of a grassroots fund-raising effort that would enable the 1927 opening of Alumnae Hall.

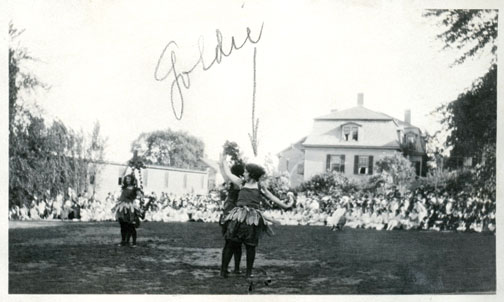

Michelson participated in many beloved women’s traditions of her era, such as Sophomore Masque, an intricate dance and theater performance with mythical themes that used the entire Pembroke campus as its stage. She was listed as one of the six Marguerites when the full cast of fifty-seven was listed in the Providence Journal. Michelson also acted in the Komians, an all-women’s theater group, previewing her later theater involvement in Worcester. Her productions for the Komians (a sly takeoff on Comus, a symbol of drunkenness and mirth) included The Wonder Hat, a comedy by Kenneth Sawyer Goodman and Ben Hecht, and George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. The Sepiad Supplement student newspaper (which preceded the Pembroke Record) said of her performance in The Wonder Hat, “Goldie Corash delighted the audience as the common-sense Margot.”

The Roaring Twenties were a spirited time, with dancing, drinking (despite Prohibition), and partying on the upswing, and cracks in Brown’s stolid facade could already be seen. Conservatively dressed women—it was scandalous to go to the men’s campus or downtown without wearing a hat—began pushing for more daring fashion choices. There was dancing all over campus, but a favorite spot was the Sayles Gymnasium, where dancing accompanied such songs as the hits “Barney Google” and “Yes, We Have No Bananas.” High-buttoned boots and the first “nude”-colored stockings made an appearance. Hairdos now included bobs, with or without spit curls. Singing and songwriting were undergoing a kind of craze at Brown, with hundreds of new songs written and performed on campus, seemingly for any occasion. Ukuleles were the hot instrument.

The humor magazine The Brown Jug began publishing in 1920, and the cover of the first issue displayed a girl in a party dress and a hat holding a small bear. The magazine produced an early, enduring talent: S.J. Perelman ’25. Perelman started as a cartoonist at the publication and became a writer. His work for the New Yorker and with the Marx Brothers later made him one of the most celebrated humorists of his time.

In 1924, an English instructor named Percy Marks published a novel called The Plastic Age, which described life at “Sanford College,” thought to be a thinly veiled version of Brown. The book included some racy scenes, including one in which college women were checking the fit of their corsets before a dance. Although The Plastic Age was banned in Boston, it was the second-best-selling novel of the year and later became a movie starring Clara Bow. Michelson’s class won a humor competition with a send-up of it called “The Plastered Age” by E.Z. Mark. The administration was not fond of the publicity, and Marks’s teaching contract wasn’t renewed. There were protests, including from Perelman, but the administrators stood firm.

When the class of 1922 men decided it was time to bring back a live mascot—the last one was in 1900—they brought in a bear named Bruno just weeks before their Commencement. He was housed temporarily in Arnold Laboratory while a permanent home was sought, but unfortunately he got into some poisonous chemicals. The Providence Journal reported on July 11, 1922, that the bear “whose spirit and talent for research might have won him a PhD, flunked out of the world on elementary chemistry.” The next year, a replacement was found and taken by truck to be seen on the sidelines during a Brown football game against Dartmouth played at Boston’s Fenway Park.

Michelson was one of five Jewish students in her class, and one of the first fifty Jewish women at Brown. Michelson told her daughter she didn’t experience direct anti-Semitism at Brown, but in oral histories assembled by the Pembroke Center years later, other Jewish contemporaries reported feeling as if they stood out and were often excluded from such social activities as fraternity dances. Mandatory chapel attendance five days a week was part of campus routine, and although those gatherings were not focused exclusively on religion, they included a good amount of Christian singing and studying. As was the case at most prestigious schools of the time, quotas kept down the number of Jews. It was worse for the smaller number of African American students on campus. (Ethel Robinson ’05 had been the first female African-American student.) Michelson and some of her contemporaries cited a number of cases in which these students faced clear discrimination, including not being allowed to live in dorms.

Despite these issues of prejudice, for Michelson her senior year was a heady, sentimental time. In April 1924, poet Carl Sandburg spoke and played guitar in Pembroke Hall. The Pembroke Record noted, “It was an afternoon that Brown girls will long remember.” Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay and philosopher and writer Bertrand Russell were among the other cultural figures who spoke at Brown that year.

On May 24, the Women’s College held its annual May Day celebration, which the Providence Journal described as “Pembroke Girls Hold May Frolic”: “While bobbed-hair maidens may be in power in the college kingdom every other day of the year, on May Day it is the girls with long, luxurious tresses that are at the center of attraction.” By rule of Michelson’s class, no girl with bobbed hair could be chosen queen or maid of honor.

At Ivy Day on June 16, lines of undergraduate women in white dresses, followed by seniors in caps and gowns, carried a chain of ivy from Pembroke Hall to Sayles Gymnasium. President Faunce said to them: “I charge you to know the joy of noble, spiritual living.” Dean Margaret Shove Morriss—who had just started the previous year and who would get much credit for having elevated the school by the time she retired in 1950—said: “You owe it to the community not to be swerved by eloquence and specious argument.”

Commencement on June 18 was a day full of ceremony for Michelson and her classmates. Honorary degrees went to Boston Herald editor Robert Lincoln O’Brien, Rhode Island Supreme Court Chief Justice William Howard Sweetland ’78, and Japanese ambassador to the United States Masanao Hanihara. In a procession separate from the men, Michelson and the other women preceded them to the First Baptist Meetinghouse, where crowds were celebrating outside. Women had only started marching through the Van Wickle Gates in 1922, and the men’s and women’s processions wouldn’t be joined until 1926.

After graduation, Michelson stayed involved with Brown, largely through the Worcester Brown club. She married in 1926, gave birth to her daughter in 1931, and earned her master’s degree in 1936 at Clark, in Worcester, where her thesis, “A Citizenship Survey of Worcester Jewry,” examined the reasons many of the city’s older Jewish residents chose not to pursue American citizenship. Michelson went on to help many social service agencies in the city. She taught English to immigrants and conducted speech therapy. She gained renown for building a community theater program with her husband, David, who died in 1974. She continued her theater programs until she was well into her nineties, and she endowed a drama fund and the Michelson Theater at Clark.

After she reached the age of 100, Michelson saw her fame grow. When asked the secret of her longevity, she often attributed it to long walks. In fact, standing on her own two feet unassisted was a matter of pride. Near the end of her life, when it was suggested she begin using a walker, she refused.

“That’s for old people,” she said.

Noel Rubinton is a BAM contributing editor.