What words would you look for to determine if someone was seriously considering suicide? Intuition suggests such obvious candidates as die, overdose, or kill. But with the help of data she’s gathered over the past four years, Nancy Lublin ’93 knows better. More accurate predictors of trouble are ibuprofen, Advil, or aspirin. “If we see those words,” she says, “it’s sixteen times more likely than if we see the word suicide that we’ll end up calling 911.”

For young people, typing on their smartphone keypads feels more natural than dialing up a stranger. Texting also happens to be very discreet, making it possible to text for help while in the same room as an abuser or from the school cafeteria, which is often the ground zero of an eating disorder. Since the organization was founded in August 2013, it has exchanged more than 30 million messages with people in crisis, 75 percent of whom are from texters under the age of 25. Lublin’s approach is arguably the biggest innovation in help lines since 1953, when English vicar Chad Varah started the first suicide hotline in the crypt of his London church.

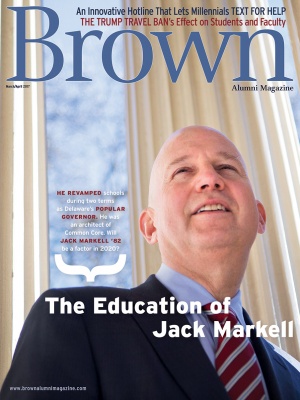

A TEXTED CRY FOR HELP

Until 2015, Lublin was CEO of DoSomething.org, a nonprofit organization connecting young adults with community service opportunities. Four years earlier, she’d learned of a chilling text DoSomething.org had received while texting its teenage members, something it routinely did. “He won’t stop raping me,” the text said. “It’s my dad. He told me not to tell anyone. R u there?”

Stunned, devastated, and feeling powerless to help this young woman, Lublin knew she had to do something. Over the next two years, while still working full time and full tilt at DoSomething.org, Lublin raised money, assembled a team, and toured crisis hotline facilities to learn how they work. Two years later, she founded Crisis Text Line.

Lublin and her team launched quietly, first rolling out services in Chicago and El Paso in August 2013. Four months later and with no advertising, the hotline was getting dings from all over the United States. Currently, Crisis Text Line fields texts from 1,500 people per day (a number Lublin hopes will reach 2,500 by the end of 2017), and helped 360,000 texters in 2016 alone, still with no advertising beyond word of mouth.

Lublin loves offering a potentially life-saving direct service, but she’s particularly excited about the data Crisis Text Line is collecting along the way. “I’m not really comfortable just helping that girl with counseling and referrals,” she said in her first TED talk in 2012, referring to the incest text that launched the organization. “I want to prevent this shit from happening.” And that’s where the industry-disrupting aspect of Lublin’s achievement comes in. Because the counseling is text-based, all messages that come through Crisis Text Line are time stamped and searchable for trends and patterns. It makes for what Lublin calls “a really juicy corpus,” a motherlode of data that can be used to figure out how to help people more effectively and maybe even how to prevent some of the worst outcomes.

In the four years that Crisis Text Line has been providing services, the organization has amassed what it claims is the largest mental health dataset ever collected. All 30 million messages in the Crisis Text Line dataset contain the full transcript of counselors’ interactions with people in crisis, something neither the Centers for Disease Control nor the National Institutes of Health, the leading sources of large-scale mental health data, is able to provide. That means Crisis Text Line’s data can offer more precise and targeted insights into a panoply of mental health issues, including bullying, self-harm, depression, substance abuse, and sexual abuse.

At the time of this writing, Crisis Text Line has exchanged more than 31 million texts, a number that you can see refreshed every hour on crisistrends.org, a platform created by Crisis Text Line on which the organization infographically presents its most compelling aggregated data: the most common crises are displayed by time of day, day of week, over time, and by state. You can also see “word clouds” showing the thirty-five most common words used when texters talk about specific issues, from bullying to bereavement to LGBTQ issues to substance abuse. The word mom appears in almost every cloud, something that might be expected when 80 percent of texters to Crisis Text Line are under twenty-five years old. Thirty percent of conversations the organization’s counselors handle focus on suicide and depression.

Lublin wants researchers, policymakers, school administrators, and journalists to use this vast storehouse of information to help trigger new studies, shape mental health policies, make schools safer, and publish stories with data powerful enough to sway public opinion, eliminate stigma, and incite action.

NATIONAL MENTAL-HEALTH INSIGHTS

This approach represents a change for Crisis Text Line, which until recently kept the data to itself while an ethics committee, mindful of the need for client confidentiality, developed guidelines for its dissemination. Meanwhile, the organization’s in-house research turned up important and surprising findings. The peak hour for substance abuse, for example, is 6 a.m. Sundays are the worst day for people struggling with suicidal thoughts. Surprisingly, the holidays, for young people at least, aren’t as bad a time as generally perceived; between Christmas and New Year’s in 2016, Crisis Text Line saw its traffic actually go down, as fewer texters complained about anxiety. “Largely, I think,” Lublin posits, “people [this age] are sleeping.”

Crisis Text Line also serves as a kind of societal barometer, Lublin says, “taking a pulse of the country at any point in time. When the Orlando massacre happened, we did see an increase in texters—an increase in texters from that area, an increase in texters who were LGBTQ. We do reflect the nation’s heart.” After the recent presidential election, she reports, Crisis Text Line saw a similar spike in fear, particularly over LGBTQ issues. Lublin also noted that a number of sexual assault survivors contacted the Crisis Text Line. “Should I bother going to the police?” she recalls a sexual assault victim asking. “Who’s going to believe me when we just elected a president who gropes people?”

While Crisis Text Line has the data to predict when and where such issues as suicidal ideation might peak, the organization does not attempt to answer the biggest question: why? “There are a lot of people out there that know a lot more than we do to answer the why questions,” Filbin says. “That’s why we created this whole open data system—to share research with academics.” The ethics committee’s first step was to come up with a rigorous application process, now open only to researchers affiliated with a university or a research institution with Institutional Review Board approval. “From day one, this was the goal,” Lublin says: “to help people one-on-one and to leverage the data for smart system change on a broad scale.”

The organization has now received more than 100 applications. Accepted research projects include one at the University of Colorado’s Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect, which wants to track the most common words texted in by abused minors. The findings, the center believes, will help Crisis Text Line counselors, primary care doctors, and caregivers ask relevant follow-up questions. Another project, based at the University of Utah’s Brain Institute, is looking into the possibility of a link between high altitudes and higher rates of depression and suicide due to hypobaric hypoxia—altitude sickness—which, among other things, changes levels of dopamine and serotonin in the brain.

Filbin, who was one of Lublin’s first staffers, is thrilled with the organization’s commitment to data. “It’s a whole other layer of impact that few not-for-profits are doing. We’re hoping part of the value of what we do is setting that precedent. Data doesn’t just mean filling out your evaluation for your funders at the end of the year; it means actually improving your service with the data in itself.”

Filbin says the data collected has allowed Crisis Text Line to design an algorithm to help identify which texters are in the most urgent need of help. Instead of taking texts as they come in chronologically, the algorithm designates a texter “Code Orange” when high-risk language appears in an opening text, allowing that texter to move immediately to the front of the queue. During a recent user spike, low-risk texters experienced a wait time of around five minutes, while the wait for high-risk texters was forty-two seconds.

When people ask Lublin if the plan is to eventually replace human crisis counselors with chatbots, she answers with an emphatic no: “Our philosophy of using technology and data is not to replace humans. It’s there to make humans faster and more accurate. We think if you text us, you deserve to have a human respond.”

The blend of very smart tech and very caring humans has attracted interest from a variety of high-tech funders. In 2016, Crisis Text Line raised nearly $27 million from such donors as The Ballmer Group, founded by former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer; The Omidyar Group, the philanthropic investment firm of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar; Reid Hoffman, the co-founder of LinkedIn; and Melinda Gates.

"Crisis Text Line is a powerful way to reach young people in need using a technology they know and trust,” Gates said in a press release announcing her financial support. “I am inspired by Nancy’s deep understanding of the power of connection, and her track record shows that she knows how to turn a simple text message into an instrument that can transform lives.”

A NIGHT AT THE HOTLINE

On a rainy Monday night in San Francisco at the Crisis Text Line’s Bay Area office, the Bay Area Director, Libby Craig, walks me through screenshots of the Crisis Text Line platform. It looks like a combination of Gchat and Slack, with message boxes for conversations with texters and a variety of channels with which counselors can talk among themselves. Volunteers must be eighteen years old or older and must complete a thirty-four-hour training over seven weeks, which culminates in a final interview and a mock-counseling session. Though all Crisis Text Line counselors volunteer remotely, there’s a real community feel to the platform, with an entire channel dedicated to counselor self-care. Another channel offers a space where volunteers can get help for or can debrief from tough conversations with fellow counselors on the same shift.

During her shift, Casey talks me through three conversations. (To protect texters’ anonymity, I’m not allowed to see the conversations as they occur on-screen.) One session unfolds with a “third-party texter” writing in about his best friend who had attempted suicide before, was currently depressed and refusing resources, and was living alone overseas. The second conversation was with someone struggling in a romantic relationship. The third was a texter experiencing loneliness and isolation in a living arrangement. Casey did a risk assessment with each texter at the start of each conversation and then worked with each one on a plan to get through the night.

“It’s really in-the-moment crisis counseling, not ongoing therapy,” Casey explains. “There might be a plan to chill and watch YouTube videos tonight and tomorrow, or sometime this week going to your school counselor, but we don’t get much farther than that.”

In between texts, Craig tells me about Crisis Text Line’s latest projects in the Bay Area, which includes a new partnership with the Golden Gate Bridge. Thirty signs listing the number for Crisis Text Line are now posted around the Bridge’s parking lot. The organization has also begun working directly with Bridge Patrol. “They were really interested in partnering with us,” Craig says, “because they’ve seen a five-fold increase in the number of young people under twenty-five who have come to the bridge over the past decade. They see people that are on their phones, texting, on the other side of the ledge.” Since the partnership launched in November, Crisis Text Line counselors have fielded sixty-seven conversations involving the Golden Gate Bridge, eighteen that included “GGB,” the keyword the parking lot sign urges texters to use and a tip-off that the texter is probably already there.

In a lull in Casey’s conversations, talk turns to Lublin. “I’ve been on the [computer] platform and said, ‘Hey, I need some help. I don’t have a good reference for that,’ and Nancy is the one that responds” on the support channel counselors use to consult each other for advice, Casey says. “She volunteers on the platform. Then I was like, wait. It’s probably two o’clock in the morning East Coast time. I don’t know if she just never sleeps or what.”

“I think she’s fearless,” Craig adds. Indeed, Lublin is tenacious, inquiring, passionate, and fast-moving, and has apparently always been those things. When asked to write an essay in ninth grade about a world leader she admired, Lublin chose Attila the Hun. She has also been accomplished from a very young age. At twenty-four, with a $5,000 inheritance from her great-grandfather, Lublin founded the now-national nonprofit Dress for Success during her first year of law school at NYU. At thirty, she left Dress for Success and in 2003 become CEO of DoSomething.org to save a failing organization. Twenty-one of twenty-two staffers had been laid off, and the nonprofit was $250,000 in debt. By 2015, when Lublin left to devote herself full-time to Crisis Text Line, DoSomething.org was netting $24 million in revenue and enjoyed a member base of 3.6 million.

What makes Lublin fun to listen to is that, more often than not, she speaks like a very smart eighteen-year-old hanging out in her pajamas. Lublin describes Crisis Text Line as “very Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup-y” because it is “a true mushing together of two different cultures—heavy social work/mental health professionalism with tech start-up. At first, people were probably like, ‘Peanut butter and chocolate? What are you thinking?’ Then you put them together, and it’s delicious.” And if you want all of your information scrubbed from the organization’s servers after a conversation with a counselor, Lublin says, simply text in “LOOFAH.”

A self-proclaimed “serial entrepreneur,” Lublin says she gets bored when things start going well. By all counts, in 2016, Crisis Text Line had a very good year. But Lublin has what she calls “designs on the rest of the world.” In 2017, Crisis Text Line will launch services in English-speaking countries abroad. “Things are definitely going well, but we’re definitely still a start-up,” Lublin says. “I’m not bored yet.”

Alessandra Wollner is a writer and community organizer in Oakland, California.