The Rwandan nun sat in the confessional behind a curtain too thick for playwright Erik Ehn to see her face. She talked about the aftermath of what had happened that day during the Rwandan genocide: the thousands of Tutsis who came seeking refuge at her convent, the few hundred others who hid in a nearby garage, and the marauding band of Hutus who arrived determined to carry out wholesale slaughter. It was, in fact, two nuns who had told the Hutus where to find the Tutsis. They'd even brought the Hutus cans of gasoline for burning down the garage and incinerating everyone in it.

Ehn, who became head of Brown's prestigious playwriting program in 2009, had gone to the convent in southern Rwanda to research a play he was planning about the 1994 genocide. A devout Catholic, he wanted to understand how Catholic nuns who had taken vows to serve God could commit such an atrocity.

After speaking with the nun that day, Ehn attended Vespers with other sisters at the convent. As the psalms were sung and the Magnificat recited, the play he wanted to write came into sharper view. It would try to answer the difficult questions that had been haunting him: How had the nuns who aided the Hutu killers justified their actions to themselves? Why had they been praying while the massacre was taking place? Just what kind of God did they believe they were serving? Ehn would write a play about corrupted faith.

Before Ehn, there was Paula. For twenty-four years, playwright Paula Vogel, known around campus by just her first name, headed the University's playwriting program. She'd built it into one of the country's finest, second perhaps only to Yale's, which in the end lured her away two years ago to chair its famed playwriting department and become a playwright-in-residence at the Yale Repertory Theatre. At Brown, Vogel mentored a whole new generation of American writers: Pulitzer prize–winners Lynn Nottage and Nilo Cruz, MacArthur fellow Sarah Ruhl, Tony Award–winner Rachel Sheinkin, Quiara Alegr√≠a Hudes, and Stephen Karam. She herself won a Pulitzer for her 1997 play, How I Learned to Drive.

These are very big shoes to fill. "No one could follow in Paula's shoes," Ehn insists. "I'll need to get new shoes." It didn't take Ehn long to signal that he intended to walk a very different path. In his first year on the job, he lengthened the graduate program's duration from two years to three. "I wanted to give the students more room to explore the wealth of resources at the University," he explains.

Ehn, who was dean of the School of Theater at the California Institute of the Arts before arriving at Brown, has also rewritten the description of the playwriting program. The MFA curriculum, according to the program's website, is "civic, chaotic, strange, queer." The term queer is defined as applying to anyone who bucks conventionality and rebels against the status quo: "a personal and demonstrated identity in contravention of logic or domination." Ehn says, "I want to live up to Paula's legacy, but I need to live up to it in my own language and on my own terms."

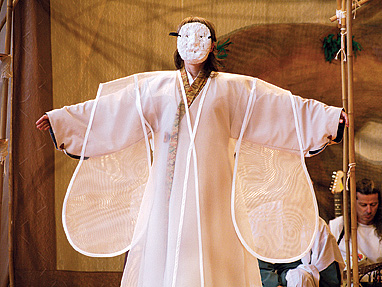

Ehn is also notorious for stage directions that appear impossible to stage (though plenty of directors have managed to do so): "A wolf jumps up from the horizon; its jaws open nearly wide enough to split its head in two," reads one from The Saint Plays. "The wolf holds the moon in two. The stars are burrs caught in the wolf's coat."

This kind of theater is not to everyone's taste. You're not going to see it on Broadway anytime soon. But Ehn, who has written at least ninety plays, simply won't compromise. "I don't believe in theater that sells objects to consumers," he says. "I believe theater is a way of life, a way of approaching the world, and you need to share that with others."

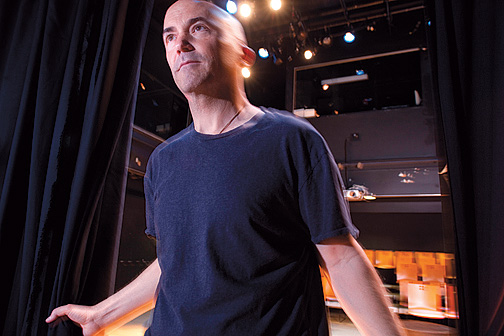

Erik Ehn is slender and of average height. His face is a near-perfect oval, and he is completely bald. He is partial to casual clothing: Dockers-style pants, a cardigan, and sneakers. A key ring hangs from a belt loop on his pants. Although his plays feature sudden, often gruesome acts of violence, he comes across as mild-mannered and relaxed. His students describe him as profoundly giving and generous, words often used to describe Vogel. "Erik is one of the most beautiful human beings I know," says Mia Chung '10 MFA, a former student.

This decency derives in part from Ehn's religious beliefs and practice, which start with traditional Roman Catholic teaching but also contain elements of mysticism, post-modernism, and theatrical performance. He sees theater as a kind of service to the community; it's where playwrights, actors, and audience come together in communion, both to give of themselves and to receive from others. The playwright creates an image, the audience interprets it, and in this shared space both parties offer and accept something profound and perhaps even holy—an intermixing of their personal creative visions.

Ehn's idealism about the theater is almost boundless. Theater, he believes, must also encompass acts of charity and public service. When he lived in San Francisco in the 1990s, he founded the Tenderloin Opera Company, in which theater artists worked with homeless people and with patients living with tuberculosis and AIDS. He has now started the program up again at Brown.

"I'm working on a project in Brooklyn right now with the Foundry Theatre that invites theater artists to give food away to a community service organization," Ehn says. "To me that's playwriting. It is social collaboration. It is focused on an idea, which is charity. It is in the moment. Item for item it is made of the same stuff that any theatrical performance is made of: how can we be together and give of ourselves? That's the essential question in theater."

Ehn, who is of Bohemian, Scotch-Irish, Native American, and mostly Swedish descent, grew up in the New York City suburbs, the child of parents who'd converted to Catholicism before he was born. After his baptism, though, they drifted away from the Church.

"It just wasn't for them," Ehn says. He felt differently. He attended Catholic private school and regularly went to Mass and confession. The early 1960s were an exciting time to be a Catholic, Ehn says, because the Second Vatican Council was meeting to overhaul long-observed Catholic teachings and practice. "I found Catholicism to be a useful tool for describing the world as I saw it," Ehn says.

As he grew older, he increasingly objected to the Church's politics, but the aspiring writer in him still found much to value in its intellectual history. Catholicism, Ehn says, views "the world as a sacramental text." The author who tries to interpret that text becomes "indistinct from the text being considered." It's this wholeness and oneness that Ehn says is "perpetually inspiring."

Ehn attended Yale, where he earned both an undergraduate degree and an MFA in playwriting. He then moved to New York City, but found himself blocked as a writer. He was writing the kinds of pieces that thrived on Broadway in the golden era of the 1950s—well-structured, thoughtful dramas and comedies with wide commercial appeal. "It wasn't any fun," he says, "and I'm no good at it." He also soon realized that "the Broadway I was writing for didn't exist anymore."

To make ends meet, he worked at a series of jobs—building elf houses for a Christmas display company in Queens, writing for Facts on File, teaching high school—and then settled into a position as the dean of studies at the National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped (NTWH) in Manhattan. It was at NTWH that his idea of what playwriting could be changed radically.

"You had to write and perform for an audience whose members were blind, deaf, or physically challenged," Ehn says. This meant moving outside the bounds of conventional theater and experimenting with sound, visual effects, and language. "Every day you were invited to consider the deepest purposes of performance," he says. "You had to check every part of your vocabulary as an artist."

Ehn also became close to the NTWH's founder and artistic director, Rick Curry, a Jesuit brother. Curry helped him understand that he didn't have to travel far to find a subject to write about; he could draw plenty of material from his religion. Ehn began to read Catholic thinkers such as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, social activist Dorothy Day, and author Thomas Merton. "I realized," Ehn says, "that I could get to a lot of places I needed to get to through the history of Catholic thinking."

It was the tradition of mysticism as practiced by such saints as Ignatius of Loyola and Teresa of Ávila that most intrigued Ehn. Mysticism is not, he says, someone levitating or "shapes spiraling out of your head. It just means that you are here and largely at peace." Mystical moments happen to us every day, according to Ehn. They occur when the outside world connects with our consciousness in such a way that we are aware of neither. The two fuse imperceptibly together.

Ultimately, the goal for Ehn as a writer is to open himself to what the external world is telling him so he can record it on paper, what he terms "complete acceptance."

"As an artist, you want to make way for the world as the world is expressing itself," he says. "You're not trying to make room in the world for your personal expression." It's a vision of the artist as conduit and messenger, as if he were a supplicant hoping to receive guidance from God.

In 1990, Ehn moved to San Francisco and soon landed a job as the literary manager at the Berkeley Repertory Theater. It was around this time too that he married his wife, scenic artist Patricia Chanteloube-Ehn. Then, a few years later, the Performing Arts Journal published Ehn's The Saint Plays, each a short meditation on the life of a saint. "Polio Comes From the Moon" tells the story of the nineteenth-century French girl Bernadette, who while out gathering firewood began to have daily visions of what later was thought to be the Virgin Mary. In the traditional telling, everyone doubts Bernadette, but she persists, bears witness to a miracle, and eventually has a chapel erected in Mary's honor.

In Ehn's play, Bernadette once again faces off against her doubters, but in the end she leaves the forest where she had her visions and returns to Lourdes, her hometown. What requires a true act of faith, Ehn is saying, is not belief in miracles and visions, but belief—and struggle—in the real, quotidian world. "The heroes of Lourdes are the ones who are strong enough to leave the hillside at all, before any promise has been fulfilled, or even made," one of the characters says in the play. Over the years, Ehn has expanded on his original work to write short plays about one hundred other saints. More than a dozen of them have been collected in his book The Saint Plays.

As he became increasingly experimental, Ehn realized there was no room for him or his work in mainstream theater. In 1993, in an essay in the Yale School of Drama's Theatre magazine, he issued what was essentially a manifesto. He declared the country's larger theaters all but dead. They are "liberal, static, and sad," he wrote. Instead, he called for the formation of a new network of small experimental theaters called Regional Alternative Theatre or RAT, for short. Together and in cooperation, they would create a radical new vision of what was theater.

Within a year, dozens of theaters had signed on, though Ehn stresses, "There was no real membership. It was anarchist." No one was officially in charge. The group never adopted formal guidelines or set an overarching goal. "This is the Big Cheap Theater," read the now defunct RAT's credo, which was penned by Ehn. "We hold the right to fail, to scatter, to let go, to re-form improbably, to infiltrate, interdict, self-contradict, disavow the principles set down here, to make space when all space was thought collapsed, to make that space habitable by infusing a portable, repeatable sense of home: residence at tempo." It then concluded, "Write your own damn manifesto."

In 2001, Ehn made his first trip to Rwanda. He had read in the newspaper about a trial in Belgium of two nuns, both Hutus, who were being charged for their role in the genocide against the Tutsis. Ehn says he'd been looking for a way to write about the "spiritual history" of genocide—its connection to God, the religious beliefs of its perpetrators. "This gave me a way to do it," Ehn says.

By this time, he was making his living teaching. He did stints at the University of Iowa, UC San Diego, the University of San Francisco, and Princeton before landing at CalArts. On his first two trips to Rwanda, Ehn went alone, but then, in what has since become an annual pilgrimage, he brought along some of his students. They interviewed clergy and local residents and visited a memorial site where the victims of genocide have been left out in the open, preserved in lye.

Ehn thinks the U.S. government and the Catholic Church did too little to stop the killing in Rwanda, and his play is an attempt at understanding his culpability as both an American and a Catholic. He sought, he says, to bear witness to the atrocities committed by the perpetrators. He says it's the same motivation a congregation might have in retelling the story of the Passion and in particular, reciting the words of Jesus' persecutors: you work your way through the evil acts to achieve a deeper understanding of what happened.

"In the end, by admitting the ways we have worked against God," Ehn says, "we make ourselves available to grace, and Christ may bring the penitential into communion."

The play's main character—and its title—is Maria Kizito, one of the two nuns being tried in Belgium. (It can also be spelled Kisito.) The language in the play, which had its debut at the 7 Stages Theater in Atlanta in 2004, is highly lyrical and filled with poetic imagery. It intersperses actual testimony from witnesses with poetic lamentations from Kizito and her fellow nuns. Ehn says the language is supposed to evoke the Psalms. "My heart has become like wax, it melts away within," Kizito wails. "So wasted are my hands and feet that I can number all my bones."

At times, it seems as if Ehn is searching for a poetical way of expressing the nun's warped state of mind, one where she could imagine she enjoyed God's grace even as she went about aiding in the murder of thousands. "My heart is a jerrican, a jerrican of gasoline," Kizito says, referring to the gasoline containers the nun brought the Hutu attackers so they could burn down the garage where the Tutsis were hiding. "My mind is evaporation, my fingers are my shadow and my body is a lie."

In the end, though, Kizito cannot—or at least chooses not to—admit culpability. "No—they lie," she says. "We tried to save lives."

About a half dozen of Ehn's students are gathered in the black box of the McCormack Family Theater to perform a dance called the Hucklebuck. For those who can remember, in an episode of The Honeymooners the Hucklebuck was the set of moves Norton tried to teach Ralph so they could take their wives out on the town. Ehn has asked the students to mimic the movements of Ralph and Norton while they watch the Hucklebuck scene play out on a large screen. Ralph and Norton shimmy and twirl, looking like asses. The students, thoroughly enjoying themselves, follow suit.

In the class, Ehn also has the students meditate, recite Shingon Buddhist chants, and stand in a circle and repeat each other's words. Meanwhile, he calls out inspirational phrases—"Can you be free? Can you make your choices freely?"—and states paradoxes—"Write impersonally to write freely and then you can discover the truly personal."

The class is Practice: Exploring Contemplative Practice in Creative Process, and it teaches the students how to use Buddhist and Catholic teachings to stimulate creativity. (A RISD professor teaches the Buddhist component.) Ehn says he is trying to free the students of the conventional concept of theater by having them experiment with sound, movement, and language. He also hopes to help them understand and achieve what he calls mystical moments—not visions of angels or a belief they can fly, but openness to the world around them and the capacity to receive inspiration. There are readings from Thomas Merton, the priest Dom Aelred Graham, Teresa of Avila, and the Buddhist scholar Chögyam Trungpa.

In all his classes, Ehn zips from topic to topic. A reading of a Caryl Churchill play is followed by YouTube clips of the minimalist composer John Cage on a 1960 TV game show and then by a racist Looney Tunes cartoon from World War II called Tokio Jokio. Another time, he paired a reading from that day's Mass with what is ostensibly an interpretation of the Book of Daniel by the rap group the Beastie Boys.

The connections between subjects can seem elusive, even nonexistent. But that's how Ehn both thinks and writes, deliberately leaving gaps between ideas for others to fill. As a postmodernist, he also believes we live in profoundly disjointed times where, in fact, things don't always add up to something coherent. He wants to get his students to view the world as a collage of overlapping, semirelated, and contrasting ideas and practices where the low- and high-brow constantly mix. At CalArts, he enjoyed a reputation as an outstanding teacher.

It's true that to an outside observer knowing little about Ehn or his plays his classes might seem downright bizarre. Ehn, though, believes he's teaching the students vital skills. For him, these are the steps you need to take to become a writer.

Lawrence Goodman is the BAM's senior writer.