District Court Judge Joseph Tauro ’53 arrived at the sprawling 845-acre grounds of the Belchertown State School on a beautiful spring day. Visiting for the first time, Tauro thought the array of Colonial Revival buildings and rolling lawns looked more like a prep school than the site of the horrors he’d been told were here. When he heard the birds chirping above the manicured green lawns located just ten miles outside the bucolic town of Amherst, Massachusetts, Tauro’s first thought was: This is a waste of time. What are we doing here?

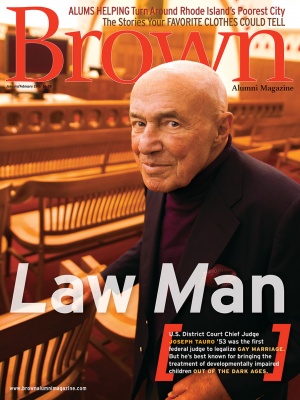

Inside the buildings naked residents slept huddled on the floor. Flies and mosquitoes were everywhere, Tauro recalls, and insect bites covered the bodies of residents. Instead of given them baths or showers, staff members laid residents on a concrete slab and hosed them down. Tauro remembers seeing “clogged plumbing, unattended residents drinking out of commodes, and an overwhelming stench of urine and feces. And there was just incessant screaming … , a soundtrack of horrible screaming.” Tauro’s account of this visit—as well as his thoughts on many other pivotal moments in his career—appears in Benchmarks XXIV: The Life and Legacy of Joseph L. Tauro. Written by lawyer Richard Belin, the 2011 book was commissioned by the U.S. District Court as the first in a series of judicial biographies.

Benchmarks details how, after Tauro had checked out Belchertown, he convened the lawyers in the parking lot. “He told us,” recalls Beryl Cohen, the lawyer representing the residents, “there would be no need for a trial because he had seen enough evidence. He collapsed the entire case right there in the parking lot.

Not only would Tauro rule in favor of the residents, he would go on to spend the next two decades overseeing reforms leading to more humane treatment of the developmentally disabled, who at the time were largely warehoused out of sight and forgotten. Ruling in this and four other related cases, Tauro forced the state to spend millions of dollars to bring its schools for the disabled “closer to the twenty-first century than the nineteenth century,” as he said that day in the parking lot. In time, Massachusetts became a national leader in caring for the developmentally disabled, thanks in large part to the changes Tauro relentlessly enforced.

Forty years later, in the fall of 2013, Tauro announced he would retire from full-time duties at the district courthouse. (He would still oversee criminal cases and assume the status of a “senior” judge.) Mulling over his four decades on the bench, he still counts the Belchertown case as one of his proudest accomplishments and a model of judicial behavior. Although he rejects the concept of an “activist judge” that has become so controversial in recent years, he believes that a judge should be unafraid to use the U.S. Constitution to protect society’s most vulnerable members.

“I don’t mean to sound immodest when I say this,” he says, “but what we did changed the earth for those people. They were the most helpless of the helpless.

In Tauro’s view, his approach in all these cases has been “moderate” and his judgments framed with common sense. Unlike more ideologically driven jurists, he has often dismissed cases on the grounds that the plaintiffs should have taken their arguments to legislators rather than to judges. For example, in two related cases separated by a generation—Drinan v. Nixon in 1973 and Doe I v. Bush in 2003—Tauro ruled that decisions about war and peace are the prerogative of the legislative and executive branches alone.

In Drinan, named after the Jesuit and liberal Massachusetts Congressman Joseph Drinan, a group of Congressmen argued that the U.S. bombing campaign in Cambodia during the Vietnam War was a violation of domestic and international law. In Doe, a group of military families and members of Congress argued that President George W. Bush lacked authority to invade Iraq. In both cases Tauro held that plaintiffs had raised a “political question” best decided by the other branches of government.

“He’s not a judge who’s going out in search of something he can do to make an impact on the world and is willing to twist the law in order to do that,” says Judge Michael Ponsor, who clerked for Tauro in the 1970s before ultimately becoming his colleague on the U.S. District Court bench. “He’s someone who does what he thinks is right, meaning, what he thinks the law requires.”

Ponsor points to another case that came up while he was still a Tauro clerk, a case that Tauro called one of the toughest he’d ever faced. In 1976, Boston had an at-large system of electing its school committee: all the seats were filled by citywide referendum, thus diluting the voting power that a district system would give to neighborhoods, including those that are predominantly black. For years this meant the committee remained all white, even as the majority of Boston public school students were children of color. At the time, Boston was only two years into its court-mandated school desegregation plan, and forced busing had been increasing racial tensions.

In Black Voters v. McDonough, a group of African American voters in Boston argued before Tauro that the at-large system violated the Voting Rights Act. They asked the court to replace it with a district-based voting system, which would give black voters greater impact.

“The lead counsel for the plaintiffs was just spectacular,” recalls Ponsor, who worked closely with Tauro on the case. “I know Judge Tauro was incredibly impressed by her closing argument. If he were someone who was interested in expressing his own values regardless of the law, he could have. But he didn’t.”

Tauro declined to intervene, finding, again, that the issue before him was political rather than judicial. “The responsibility for providing quality education for all Boston’s school children is a universal, city-wide problem,” he wrote in his ruling. “Those elected should have the well-being of the entire population in mind as they make their decisions. The fact that some may not have lived up to this responsibility may be good cause for removing them from office, but their failure is not adequate cause to suspend the Charter of the City of Boston.”

When he characterizes his own politics, Tauro can sound like an endangered species. He calls himself a “Volpe Republican,” a reference to former Massachusetts governor John Volpe, under whom he served as chief legal counsel for four years in the early 1970s. Like Volpe, Tauro is socially liberal, fiscally conservative, and generally pragmatic. Friends and colleagues say his political background makes him a savvy judge who knows how to broker a settlement among seemingly intractable parties. As chief judge, Tauro is known for what his longtime friend and U.S. District Court colleague Judge Douglas Woodlock calls a tone of “meaningful collegiality” even during contentious times.

“His willingness in these high profile cases to deal with questions of transparency and publicity was somewhat unusual at the time,” Woodlock says. This “maybe gained him a reputation of being more rigorous than judges usually are. Nobody would accuse him of being a potted palm.” Yet his fundamental approach is to hold society’s institutions “responsible for their duties,” Woodlock says. “That’s what a judge is ultimately supposed to do.”

“I’m no rebel,” Tauro says. “I don’t feel as though I’m free to start the world all over again.”

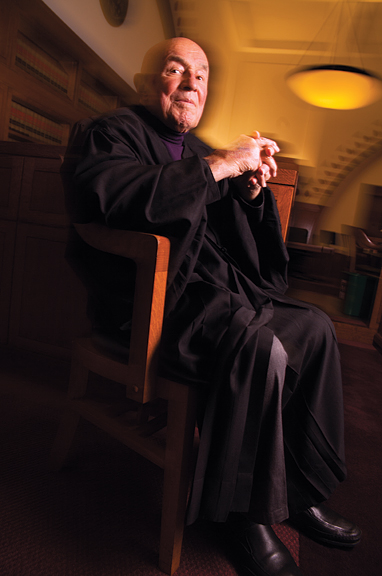

It’s a Monday morning in March, and Tauro’s law clerks are helping him on with his robe. The robe belonged to Tauro’s father, G. Joseph Tauro, a distinguished judge who served first as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court and later as Chief Justice of the state’s Supreme Judicial Court. (“I think we were the only state Chief Justice/federal District Court Judge father-son combination ever,” Tauro notes.)

One of Tauro’s fondest childhood memories was of standing outside Fenway Park, waiting to ask Red Sox players for autographs. Although he was a serious baseball player in high school and at Brown, he says he realized that “I was a very good high school baseball player, and a mediocre college player. So when I got to Brown I realized that as good as I was to make the varsity, I was never going to make a living playing baseball.” So, always close with his father, Tauro decided to follow him into “the family business.”

Tauro loves music and show business—he’s still proud that he personally brought Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra to campus one year for the Interfraternity Governing Board Ball—and the night before he was to leave for law school he had a change of heart. What he really wanted to do, he told his father, was manage dance bands. The elder Tauro had an unexpected reaction.

“He was so cool, lying down in bed, reading Time magazine,”

Tauro says. Mimicking his father’s little shrug of the shoulders, he

recalls his father saying, with little interest, as if remarking on the

weather: “Don’t go.”

“I went,” Tauro says, “and I loved it.”

Now eighty-three, Tauro still carries his father’s reverence for the law, and many of his lessons, into his own courtroom. One of the most important, he notes in Benchmarks, is “to resist the temptation to be a bully.… He couldn’t stand judges who were bullies. You don’t have to be a tough guy or raise your voice in order to be respected.”

Standing barely taller than five feet, Tauro walks with a slow, deliberate shuffle down the courthouse’s plush carpeted halls. While serving as Chief Judge from 1992 to 1999, he led the effort to replace Boston’s outdated federal courthouse with a $220 million building that would eventually win several national design awards and bring the court the seriousness and respect it deserved. By all accounts, Tauro, wielding his usual good cheer and political acumen, wrangled approvals—and sizable appropriations—from dozens of imposing bureaucracies, including the city of Boston and the U.S. Congress. When U.S. Senator John McCain questioned the courthouse’s price tag on national television, Tauro was indignant. “We don’t hold the sessions of this court in a Quonset hut,” he said.

As we make our way around the facility, he nods at the chambers of his old friend U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer. (Supreme Court justices keep chambers in their home circuits). “As long as we’ve known each other, we’ve been pals,” Tauro says. “He’s such a fair, distinguished guy, everything you’d want somebody in a position of absolute power to be.”

Tauro’s current clerk, Zsaleh Harivandi, says, “Judge’s wife told me recently that, many years ago, when Justice Breyer was on the First Circuit, he and Judge used to play basketball in the halls.”

“Yeah,” Tauro says with a grin.

“June [Tauro’s wife] said you behaved like fourteen-year-olds.”

Tauro nods, smiling. “Even now.”

Tauro, Ponsor says, “is an exuberantly delightful person. The lesson that all of us who clerked for Judge Tauro learned from him was, take a huge bite out of life, and be yourself with as much gusto as you can.”

Tauro accomplishes this with a disarming combination of supreme confidence and deep humility. He never misses an opportunity to praise his staff, to point out how indispensable they are, how smart and hard-working. Yet he admits to “a great sense of confidence when it comes to my judgment. I never worry when I go home. I call it and that’s the end of it.” Ponsor says that Tauro frequently describes himself as “‘often in error but never in doubt.”

Tauro’s reputation among lawyers is that of a tough judge impatient with posturing. He says he wants to give everyone a fair shot. “When you’re a ballplayer,” he says, “you understand how you’re supposed to play ball. It doesn’t matter who your daddy is, or who your brother is. It’s how you can play that counts.”

Woodlock remembers how Tauro once handled the president of a local bank who’d been called for jury duty. The banker, Woodlock says, “came up in a kind of familiar fashion at the sidebar, talking ‘man-of-the-world to man-of-the-world’ to Judge Tauro. He said something like, ‘I’m actually a very busy individual. Of course I’d like to do my civic duty, but I’ve got more important things to do, and I’d like to be excused.’

“And Judge Tauro said, ‘Well, that’s very interesting.’ He turned to his courtroom deputy clerk and said, ‘Could you get the Commissioner of Banking on the phone? I want to be sure that he understands that at this particular bank, if the chief executive is gone for even a couple of days, the bank is vulnerable. And a vulnerable bank like that ought to be reviewed carefully by the Banking Commissioner.’ At which point the fellow said, ‘Oh, you misunderstood. Of course I will serve.’”

Woodlock chuckles at the memory. “What [Tauro is] looking for is straightforward answers and people recognizing their responsibility.”

It was this insistence on being accountable that led to Tauro’s pronouncement in the Belchertown parking lot four decades ago: “I told them there was no possible expert testimony that could convince me that the conditions I had seen were the way it was supposed to be,” he says in Benchmarks, “so instead of wasting time litigating the impossible, why don’t we go right to the remedial phase?”

By November both sides had agreed on a consent decree to address the conditions. Eventually, Tauro oversaw cases for the four other state schools. He required them all to improve their living conditions, hire better-trained staff, and reduce their populations by placing capable residents into independent yet supervised living arrangements in nearby homes.

Yet Tauro knew the changes would require the state to spend tens of millions of dollars. That’s when his political savvy kicked in. He kept pressure on legislators by inviting reporters and the state’s political leaders—including Governor Michael Dukakis—to accompany him on tours of the facilities.

Some of the legislators objected, expressing concern over residents’ privacy, and a few judges thought his grandstanding was, well, un-judgelike. “I wasn’t cowed by any criticism over letting the cameras in,” Tauro says. “It was important that the public know what was going on.”

For years afterward, Tauro held status conferences with lawyers in his chambers. He visited the schools to check on progress and threatened to shut down those dragging their feet. Frustrated by the slow pace of change, Tauro added U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler, a former Massachusetts Congresswoman, as a party to the lawsuit.

“There were federal funds involved,” Tauro says of the move, “and they were not being properly spent.” When Heckler threatened to withhold tens of millions of federal dollars, the Massachusetts legislature finally agreed to fund the implementation of the consent decrees.

In his courtroom Tauro has been sharply aware of discrimination and injustice. In the mid-1970s he struck down a veterans’ preference law that inadvertently, but effectively, excluded women from Massachusetts civil service positions. In 1998 he upheld the constitutionality of an admission system that boosted minority enrollment at the elite Boston Latin School. (Both cases were later reversed on appeal.)

He had better luck in 1989, when he fought hard to broker a settlement in a contentious case in which the NAACP claimed the Boston Housing Authority systematically denied applications from African Americans trying to get into public housing. The evidence was clear, and the city was willing to change its practices, but it refused to pay the damages the NAACP sought on behalf of the wronged families. Eventually, with pressure and careful guidance from Tauro, the city agreed to pay $3 million in damages. “A settlement,” the Boston Globe argued, “avoided a divisive trial that could have engaged the judge’s energies for years.”

For all his judicial acumen, Tauro has been exceptional in his ability to keep cases off the docket. As in the NAACP case, he has a reputation for brokering settlements between seemingly deadlocked opponents. “I find the opportunity to resolve disputes fascinating,” Tauro says. “You want to make sure you understand exactly how they feel. That’s the most important thing in the world: the participants have to feel that they’ve been heard. If they do, eventually they’ll go away satisfied”—even if the outcome is not what they had hoped.

When the issue of same-sex marriage arrived on his docket, Tauro was seventy-three. Opponents sought an injunction to block the State Supreme Court’s 2004 ruling allowing same-sex marriage in Massachusetts. “The danger for judges, who live in a bubble in which everybody addresses you as ‘Your Honor,’” Woodlock says, “is that you’re going to start believing that’s a description, not just a name that’s used honorifically in the courtroom, and get settled in your views.” Tauro, however, isn’t “pressed in amber,” Woodlock says. He denied the motion and allowed the nation’s first same-sex marriages to proceed.

Tauro wrote that “proffered rationales,” which included encouraging

“responsible procreation” and defending traditional notions of

morality, “are clearly and manifestly implausible.” He concluded that

“a reviewing court may infer that animus is the only explicable basis.”

In 2013 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Tauro’s ruling. The forcefulness

of Tauro’s judgment, Cohen argues, “gave legal and political cover for

all that has come since.”

Tauro explains that when he looked at the law, “I said to myself, ‘This

is intolerable.’ And that’s the way I wrote it. The opinion, the way it

was going to come out—that was right from my soul.”

Now that Tauro is semi-retired, he will focus mostly on criminal cases. In his magisterial dome-ceilinged courtroom, he spends this March morning overseeing four men pleading guilty to distributing heroin. One is a former professional baseball player.

On the spectators’ benches, an infant fusses on a woman’s shoulder. As she gets up to leave, Tauro interrupts the prosecutor in the middle of outlining his case. “That’s all right,” he says gently to the woman. “The baby doesn’t bother me.”

Later, he says, “Every case where someone is going to go to jail is a family tragedy of some magnitude. You’d have to be really cold-blooded to not feel the magnitude of what’s involved. There’s no such thing as a sentencing without pain.” He wonders absently what caused a professional baseball player to end up in shackles in his courtroom. “What a shame,” he says. “That’s really tragic.” Still, he says, while he has to be fair to the person going to prison, he “has to be fair to the public, too.”

Decades after his glory days on the state champion Swampscott High School baseball team, Tauro remains a great lover of sports, baseball in particular. Now that he has more time, he hopes to attend Brown baseball games and to follow his beloved Red Sox. During the 1990s he served as chairman of the Brown Corporation Committee on Athletics and calls Brown’s athletic program “one of the real powerhouses of the Ivy League.”

He rarely misses one of his six grandchildren’s soccer, baseball, or tennis games. Sports, he says, are a “great learning tool” that helps participants “develop a rubber ass.” He tells his grandchildren that “in this life you’re always going to get knocked down. You have to learn how to bounce back, get up, brush yourself off, start over again.”

As the judicial system has become more politicized in recent decades, Tauro finds himself labeled an activist judge more often—both as a jibe and as a compliment. He recalls receiving an honorary degree from Northeastern Law School and trying to “let everybody know that I am not an activist—if what you mean by that is someone who gets himself involved in areas that he has no right to because there’s no jurisdiction. I’m not that sort of an activist.”

Before the honorary degree ceremony, he made sure to clarify his position to an official at the school. Then he got to the podium and heard Northeastern’s president say how honored he was to introduce “one of our most distinguished activist judges.”

Tauro just laughed. “I thought to myself, ‘I’m never going to shake it. Just bow and say thank you for loving me as I am.’”

Contributing editor Beth Schwartzapfel is a staff writer for The Marshall Project.