Over the past few years, America’s nearly two-and-a-half-century attempt at coming to grips with the issue of race has taken on a new and urgent prominence. The nationally publicized shootings of unarmed African Americans, dating back at least to the Trayvon Martin case in 2012, have spawned the Black Lives Matter movement and angered a new generation of young blacks for whom social justice is not an abstract ideal but a matter of life and death. The string of killings has also affected students of all races and raised larger concerns about fairness and safety for a range of marginalized groups.

“What does it mean to have a vibrant intellectual community?” Paxson asks. “If everyone looks the same and thinks the same, it’s pretty hard to spark the kind of deep intellectual conversation, the new ideas, that universities are meant to encourage and inspire. Diversity, broadly defined, is what makes for a vibrant intellectual atmosphere. It’s what makes a university great.”

But admitting a more diverse student body—which began in earnest after President Ruth Simmons insisted that domestic undergraduate admission to Brown be need blind—or hiring a more diverse faculty and staff are only the beginning. “It doesn’t do much good to bring in brilliant students,” Paxson says, “if they aren’t given the support they need to be successful.” To be poor or the first person in your family to go to college, to study at a school where the faculty is so overwhelmingly white that you wonder if people like you aren’t cut out for higher education, to sit alongside wealthier students who have been aided by expensive tutors and testing coaches, to be questioned by campus security because you don’t “look like” a Brown student—these are some of the obstacles students from a variety of nonwhite or working-class backgrounds face in a majority white and affluent world like Brown.

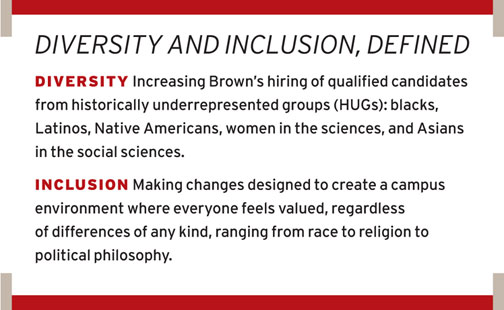

And while race, class, and ethnicity are the most obvious targets of a diversity and inclusion plan, Paxson means inclusion to include other types of difference, in such things as political perspectives, veteran status, religious views, sexual orientation, and gender identification. To solve the problems of the world, the problem-solvers must better reflect the world’s composition.

Paxson took on these issues in Pathways, which she described at the time of its release as “a set of concrete, achievable actions to make Brown a more fully diverse and inclusive community.” It is by far the University’s most ambitious and detailed diversity plan in at least three decades of trying. Along with Building on Distinction, Pathways is likely to be one of the documents that defines Paxson’s presidency. Will it succeed where so many previous plans have not?

After all, the goals of Pathways are not new. Thirty years ago a committee appointed by President Howard Swearer concluded there was an “urgent need” for a more racially and ethnically diverse faculty, and went on to note the University’s historical tendency toward lip service on the issue. Ten years ago, in 2006, the University issued a diversity action plan that called diversity a key to academic and intellectual excellence and cited research showing that students in a diverse educational environment learn better and think in deeper, more complex, and more creative ways. A major goal of that plan was to “increase the diversity of the faculty.” Yet the needle has not really moved.

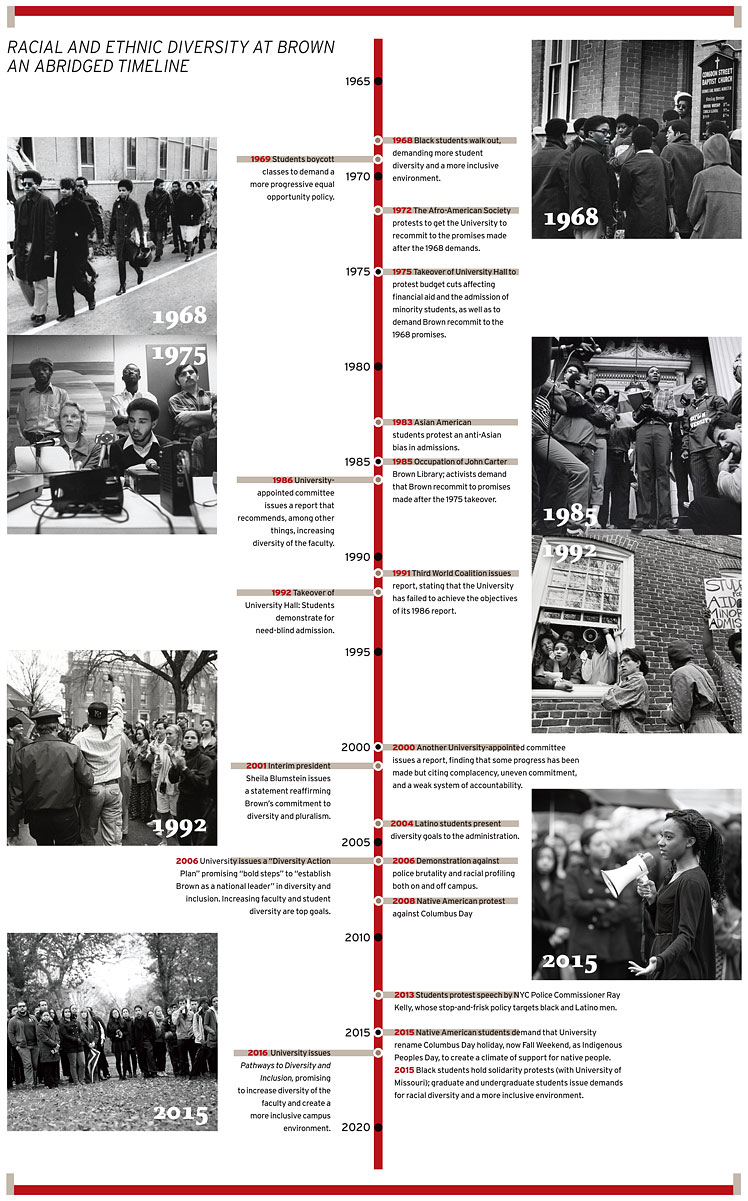

Article continues below timeline. Larger viewable version of timeline here.

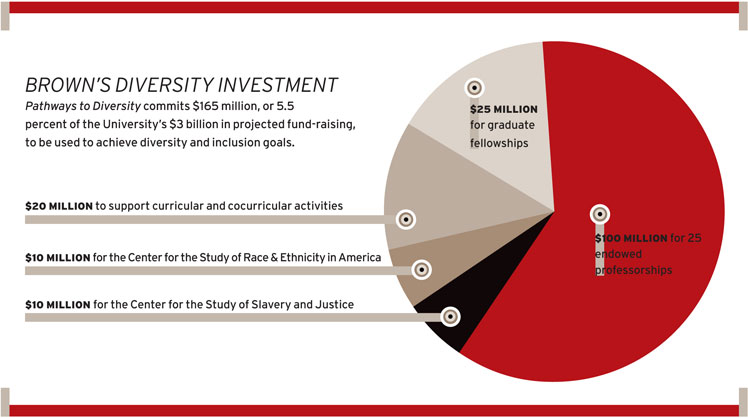

Paxson and Provost Richard Locke, while unwilling to get caught up in a numbers game, readily concede that Brown has fallen short. “We do have a trust gap in this community,” Paxson said to a crowd of students, faculty, and staff on February 23 while going over the details of her plan.The Pathways document commits about 5.5 percent of the University’s projected $3 billion in new endowment over the next ten years (see chart, page 31). A majority of those funds will be aimed at building increasing faculty diversity and creating graduate fellowships that will identify qualified members of underrepresented groups and get them into Brown’s hiring pipeline. The plan promises to transform attention to diversity and inclusion from generalized good intentions voiced every five to ten years to specific structures and policies, with an implementation timeline. It will affect almost every aspect of the operation of the University, from student and faculty recruitment to campus climate.

Pathways offers a level of specificity not found in earlier diversity plans at Brown. For example, the vague goal in the 2006 diversity action plan was that faculty diversity “should improve significantly.” In Paxson’s plan, that becomes “doubling the number of tenure-track faculty from historically underrepresented groups by 2022.

Similarly, Pathways calls for an unprecedented level of accountability. One of the most striking requirements is that every department on campus, academic or administrative, must create its own departmental diversity and inclusion plan. And there’s a consequence to noncompliance: no plan, no new hires. In addition, a Diversity and Inclusion Oversight Board—upgraded from the existing Diversity Advisory Board and consisting of administrators, faculty, staff, and students—will conduct annual reviews of each department’s progress and then prepare an annual report to the Corporation. An accounting of progress, or lack of progress, on each of six priority areas outlined in the plan is being posted online at the new Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan (DIAP) Implementation and Progress web page.In addition to years of planning by the Paxson administration, the final version of the plan reflects two months of intense conversation—including protests—on campus. Paxson had been crafting a diversity strategy since she arrived 2012, according to Liza Cariaga-Lo, vice president for academic development, diversity, and inclusion. While developing Building on Distinction, a 10-year strategic plan for the University, Paxson charged each committee with incorporating diversity into its thinking. “She made it clear it was a priority for her,” Cariaga-Lo says.

Cariaga-Lo had finally started writing up a new diversity plan with the provost and president in early summer 2015, getting input from various students, faculty members, and administrators. The completed plan was slated to be released, as a fait accompli, by the end of the year. Then a series of events triggered a reconsideration of that approach.

First, the Brown Daily Herald published a couple of columns that the editors later conceded were racist. Then a Brown security officer roughed up a visiting Latino student from Dartmouth (the officer was later fired). At the same time, a string of racist incidents at the University of Missouri led to protests and the firing of the president there. Many students were galvanized by these events, leading them to insist on real change at Brown. At a rally on the College Green staged in solidarity with the students at Mizzou, a group of Africana Studies graduate students read off a list of demands for the administration.

These developments were among the factors prompting Paxson and Provost Richard Locke to make a greater effort at involving the Brown community in crafting a meaningful diversity plan. On November 19, Paxson released a draft and invited broader community commentary and suggestions at a website set up for that purpose. For some student activists, the openness to feedback appeared to be a PR tactic. And to them, the promises in the draft diversity plan were just as vague as the ones going back to 1968. Pointing to Brown’s history of grand pronouncements, good intentions, and lousy results, many minority students believed Pathways was more of the same. And they felt compelled to speak out. Not only had first-year students come of age in the post-Trayvon Martin era—they were in high school when Martin was shot—but they all had recently had an education in institutionalized racism, having just read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander as part of Brown’s First Reading program for incoming students. Eventually, a group of students—mostly first-years—charged into University Hall to denounce the plan as “illegitimate and insufficient.”

The plan grew and got more specific as suggestions from the website and from student, faculty, and alumni groups found their way in. Hundreds of people attended twelve forums across campus at which they could offer input. One group of faculty sent Paxson what they termed a “friendly rewriting” of the plan. In the end, the administration reported receiving 162 online submissions, thirty-five individual and group e-mails, in addition to the comments and recommendations they collected at the forums and from other sources.

Paxson says she is happy about the way things went. “I think it’s especially important in developing a plan for diversity and inclusion that we follow an inclusive process,” she says. Both she and Locke acknowledge that Pathways is stronger for all the input, but Paxson insists that the basic elements of the plan had long been in place.

For example, large investments in the Center for Race and Ethnicity in America and the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice had already been mapped out and approved by the Corporation as part of Brown’s ambition to be an academic leader in these areas. Diversity had already been presented, in the operational plan, as being key to academic excellence, and the money, Paxson says, had already been committed. What Pathways does, she says, is make the goals in Building on Distinction “more granular.”

Some student activists felt they really were being heard this time, although the skepticism and some criticisms remain. “I think reading the plan was a really emotional experience for a lot of people,” Brooks says. “A lot of people saw their ideas in it,” though she adds that “a lot of people saw their ideas erased.”

Many of the faculty members—including those who had earlier been critical of the draft plan, mainly for vagueness—also praised the final version. Professor of Africana Studies Tricia Rose ’87 AM, ’93 PhD, says she has read many such plans over the years. They tend to be heavy on the “idealized principles,” she says, but light on the details. “I’ve seen nothing of its magnitude in vision or in detail at any time in my professional career. I’ve never seen this level of concrete commitment.”

Matthew Guterl, chair of the American Studies department and one of a group of faculty members who offered extensive feedback on the November draft, says that the final document is “such a vast improvement over the first draft that most people are either cautiously optimistic or really pleased.” As for the additional red tape he’ll have to navigate as a department chair, Guterl says he is ready to roll up his sleeves. “It’s going to be a boatload of work,” he says, “and I’m not afraid of it.”

Inevitably, Pathways, by its very existence, has entered the culture wars. The national media, particularly conservative outlets, have had a heyday positioning Brown as excessively idealistic and essentially run by student protesters. “I have been somewhat frustrated,” Paxson says, “because a lot of the conversation in the media completely misses what’s been going on on campus.” Most of the reports the public was seeing were inflammatory video clips—students yelling at the president and provost—and snippets of information people posted on websites.

Critics, including some alumni, have accused Brown of creating a new quota system, prioritizing demographic diversity over intellectual and academic merit. Locke calls this a “highly unfortunate” misunderstanding. “This is a matter of ensuring that Brown is positioned to hire the best and the brightest from the full range of diverse backgrounds,” he says, “by having policies and practices in place to get these exceptional scholars into our recruitment pipeline and applicant pools.” In other words, says Paxson, “We know there are great scholars out there that we can bring into these positions.” What Pathways does is give hiring committees at Brown a structure for finding innovative ways around the self-replicating system of white administrators and faculty attracting and recruiting more of the same.

Even for those who agree with the plan, the question remains, can it be done? “Ideas are one thing,” Rose says, “but implementation will take a lot of work. It needs all hands on deck at all levels of the University.” Paxson hopes that the bumpy process, which ended up including so many in the plan’s development, will make buy-in and cooperation more likely from all members of the Brown community, on campus and off. “For us to be successful here, it can’t be just University Hall’s plan,” Paxson says. “It has to be the University’s plan.”

An early test took place in February. It was the first of the plan’s promised “professional development opportunities” around diversity and inclusion, aimed at bringing the campus community up to speed on the issues. The opening session took place at the De Ciccio Family Auditorium, Brown’s largest lecture hall, and so many people showed up that about fifty of them had to watch a simulcast in a nearby room. The afternoon workshops—one was taught by a group of graduate students that included Shamara Alhassan, who’d read off the list of demands at the protest on November 12—were also at capacity and turning people away.

Paxson and Locke say they hope Brown’s plan, and the inclusive process that was used to refine it, will serve as a model for other colleges. And as for the differences of opinion that have been expressed along the way, the administration sees that as part of the vibrant intellectual atmosphere Brown is meant to cultivate.

“Brown should be in the avant garde on this question,” Guterl says. “I don’t think we should ever pause to pat ourselves on the back. We’re supposed to be better at this stuff, but we’re supposed to be entirely skeptical of it. I think that’s a good thing. That’s the spirit of Brown.”