It was a Sunday morning in June when the world learned that Orlando, Florida, a city universally known as the home of the “Happiest Place on Earth,” had become the scene of the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history. At 10:21 EDT, Orlando’s mayor, Buddy Dyer ’80, backed by a phalanx of law enforcement officers, delivered the grim news that the number of fatalities in the Pulse nightclub massacre was much higher than had been previously reported.

“I wanted to go out and calm everybody down,” Dyer recalled in his City Hall office two weeks later. “It could’ve been a bad scene. I think we had a very calming effect when we came out. I’ve been told by people that ‘when we saw you and you were calm and strong, we were calm and strong.’”

Staying strong in the wake of the massacre has caused Dyer to feel conflicted about his state of emotional calm amid so much suffering. But his job as mayor, he stressed, was to remain collected and in control as he addressed vigils, hugged dozens of grieving people, and attended to the city’s efforts to help survivors and families who’d lost loved ones. Across the street from his third-floor office, the lawn fronting Orlando’s new performing arts center—a crown jewel of Dyer’s thirteen years as mayor—became a makeshift memorial to the Pulse shooter’s forty-nine victims. Dyer visited the site many times to take in the outpouring of sorrow.

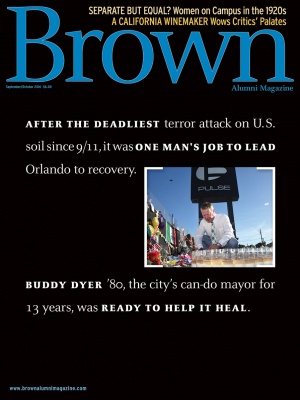

Walking among the hundreds of solemn tributes and mementoes spread across the lawn—the bouquets of flowers, stuffed animals, heart-shaped wreaths in LGBTQ colors, tiny U.S. and Puerto Rico flags, dozens of candles, and banners and posters bearing names of victims with #orlandostrong and #orlandounited—is an overpowering experience. Visitors choke back tears. Some break down, sobbing.

But Dyer wouldn’t allow himself to grieve in a place that’s meant for the grieving. He says the only time his emotions got to him was when he was dropping off his dog at the neighborhood groomers and saw a sign memorializing a young victim who had graduated from the public high school across the street. “Tears just started coming down,” he says. “I just wiped them away and said, ‘Can’t do that.’”

He recalls that, when a grief counselor called him to ask how he was doing, he replied, “ ‘I’m doing fine, but I’m not feeling the emotions I think I should be feeling. Is that wrong?’ She said, ‘No, you’re doing exactly what you’ve got to do. You have to be seen strong, you have to be seen calm, and however you’re coping you’ve got to keep doing that. And six weeks from now, at some point you’ll process this, but you really don’t need to process it now.’ ”

The son of a cattle trucker, John Hugh Dyer Jr. grew up in Kissimmee, twenty miles south of Orlando. Young Dyer got the nickname Buddy because his mom didn’t want him to be called Butch after his dad. An athletic and smart country boy in high school, Dyer set his sights on the Ivy League, which, in his view, could only mean Harvard.

But he came across Brown while researching colleges and discovered, he says, that it “was a cool school at the time. They had an alternative curriculum where you had to have twenty-eight credits to graduate, you could take them pass-fail, and you took four classes a semester. There was not a common core like most colleges have for two years. It was cutting-edge, and in my mind that was the place to be.”

Dyer considered himself an “Ivy League redneck” in Providence. He sported a beat-up cowboy hat that must have looked like an odd accessory atop his giant Afro. “The African American guys were jealous of the Afro I had,” he says, smiling. “I had a big, big Afro.”

At Brown, Dyer quickly realized that his days of being the smartest kid in the room were over. His SAT score, the highest in Osceola High’s class of ’76, was the second lowest in his freshman dorm. “There were at least three kids who had perfect SAT scores,” he says, and pauses. “Just on my freshman hall.”

A civil engineering concentrator, Dyer worked as an environmental engineer in Orlando after Brown. His plan was to work a year, then go to law school at the University of Florida. But he put off enrollment to travel across the country with a friend for two months, and afterward took a job with an engineering firm in Houston. Dyer didn’t stay long. A former colleague who had started his own company lured Dyer back to Orlando, and then the money came pouring in.

“I was making a boatload of money,” he says. “I went from making $18,000 to $45,000 [a year], so I was able to put away some money. I went to UF law school after four years of being an engineer and put myself through.”

A law career in Orlando followed, as did marriage to a lawyer. The couple have two adult sons.

Public service had been a lifelong interest of his, so Dyer, a Democrat, entered Florida politics as a candidate for the state Senate in 1992. He won the race and held the seat until 2002, when he ran for state attorney general. It was the last time Dyer would lose an election. He ran for mayor of Orlando in a special election held in 2003, winning the race on a Tuesday and going to work as mayor the following day. He’s been there ever since.

“I didn’t have time to figure out what was what,” Dyer says. But he had big plans, and he ushered in a transformational era of public and private investment in the city. Condo towers and apartment buildings were built; the city’s southern boundary became the home of Nemours Children’s Hospital, a veterans hospital, and the University of Central Florida’s medical college; sprouting up downtown were a $480 million NBA arena and the first phase of a $500 million performing arts center. Dyer also championed a $207 million renovation of the city-owned football stadium, which will host the 2017 NFL Pro Bowl; a $1.2 billion commuter rail system; and a soon-to-be-completed, privately funded major league soccer stadium. Under Dyer, Orlando emerged from the shadows of Walt Disney World, and the city’s image as a “Mickey Mouse town” faded as Orlandoans saw an urban renaissance take shape in the pre- and post-recession years.

Dyer has built an impressive record for getting things done even when forces were aligned against him, most particularly a devastating recession. Orlando Sentinel columnist Scott Maxwell coined the phrase “what Buddy wants, Buddy gets” as an acknowledgement —but not necessarily a compliment—of the mayor’s grit and determination. But Maxwell was unequivocal in his praise of Dyer in the wake of the Pulse tragedy.

“What Buddy did so admirably during a time of crisis and tragedy,” Maxwell says, “was keep the focus on the victims, rather than himself. Plenty of politicians parachuted into town, hoping to score some TV time—many offering blustery, bogus promises to get the bad guys or combat ISIS—but every time Dyer stepped in front of a camera he kept the focus on the victims. And their families. And the city. And unity.”

Focus is how Dyer got through the Pulse attack. He arrived at a mobile command center just after three a.m. while Omar Mir Seddique Mateen of South Florida, armed with semi-automatic weapons, remained holed up in the nightclub with hostages, some wounded and bleeding to death.

“So I thought what’s my role here as mayor?” Dyer recalls. “At that point I thought it was three: Stay out of the way. Don’t undermine the [police] chief’s command. Gather as much information as you possibly can, because you’re going to have to inform the public what’s going on here tonight.”

From the police outpost, Dyer could see Pulse, a square, one-story building with a dark exterior. Survivors were pleading via 911 calls and text messages to be rescued as the shooter held police at bay with threats of detonating explosives. Alongside Dyer that morning was his deputy chief of staff, Heather Fagan, who has worked with him for ten years. She describes her boss as level-headed and composed at all times. “He was very stoic and really thoughtful and taking it all in,” Fagan says of Dyer’s businesslike approach while police carried out their tactical operations.

At five a.m. police stormed the nightclub and took out Mateen in a gun battle. No explosive devices were found. At a seven a.m. news conference, Orlando’s police chief declined to give a body count but told media that at least twenty had been killed. “The first time I saw emotion from [Dyer] was between the first and second press conference,” Fagan recalls, describing Dyer’s reaction when he learned the death toll would exceed forty. “Going into that [second] press conference we discussed how to present the number. He felt very strongly that he should be the one to deliver it. He had time to prepare himself.”

Informing the public of what had happened at Pulse—that was the job of a mayor, Dyer insisted despite getting some “pushback” from the FBI. “But I knew it was important for the citizens of Orlando to see their mayor, not see some FBI agent. We needed to provide accurate, concise facts, or information, not a whole bunch of gobbledygook. We wanted to make sure people knew we were in control. We wanted to make sure people knew they were safe because the FBI at that point had determined that [the shooter] was a sole actor.”

Asked what his emotional state was like when he first heard the death toll was fifty (including the shooter) instead of twenty, Dyer relies on logic: “It was hard, but you feel the same way about twenty as you do about the fifty.”

Thousands of citizens responded to the attack on Orlando’s gay community by standing in lines for five hours or more in oppressive heat to donate blood. A candlelight vigil at the performing arts center drew an estimated 8,000 and the city launched a fund, oneorlando.org, to aid shooting survivors and victims’ families. Millions of dollars poured in overnight. “I love being the mayor of a city that is not defined by the hate-filled act of a killer,” Dyer says, “but is defined by the way we respond: the love and compassion and unity.”

At some point after a traumatic experience, life returns to normal, but it’s not always an easy transition. Dyer had a hard time resuming a sense of normalcy; it just felt “weird,” he says, to play golf and relax again.

So what’s next for Orlando’s mayor, a politician who has a reputation as unstoppable when there’s something he wants to accomplish? “I know that I’m not going to engage at least for a long period of time in the politics of gun control or terrorism or immigration,” he says, “because I think that would detract from what I need to do and what I’m uniquely able to do, which is help heal our community.”

Asked to describe his character in one world, Dyer gives the question some thought. “Solid,” he replies confidently.

Mike Boslet is a freelance writer based in Winter Park, Florida, which borders Orlando. He was editor of Orlando magazine from 2008 to 2012.