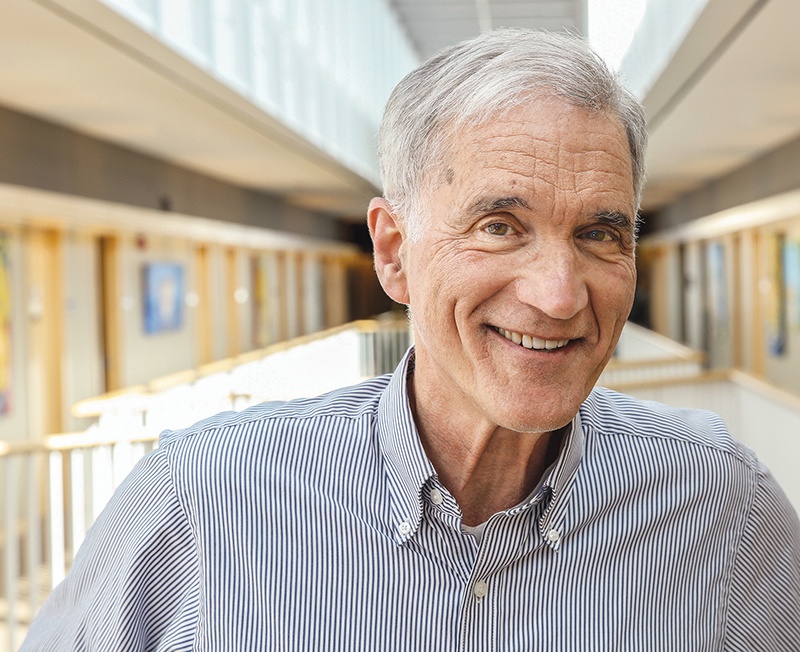

Pulitzer Prize–winner David Kertzer ’69 is one of the Brown faculty’s best-selling authors. One of his 12 books has even caught the eye of director Steven Spielberg for adaptation. After receiving his PhD from Brandeis, he taught at Bowdoin until returning to Brown as an anthropology and history professor in 1992. He was Provost from 2006 to 2011 and is the Paul Dupee Jr. University Professor of Social Science. His latest book, The Pope Who Would Be King: The Exile of Pius IX and the Emergence of Modern Europe, was published by Random House in April.

Why have you focused so much of your writing on the history of the papacy? I began in this area—politics, religion, Italy, the church— through contemporary work as an anthropologist. But I’d always had historical interest. None of my work had directly focused on the Vatican until a friend of mine, a historian, mentioned this Jewish child, Edgardo Mortara in Bologna, who had been seized on orders of the Inquisition—and the Inquisition was headed by the pope [Pius IX]—on the grounds that he’d been secretly baptized by a Christian serving girl. The case of Mortara became an international cause, with Pius refusing to release him and raising him as his own. So I began [writing about papal history] with my 1997 book about that, The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara. It’s recently gotten attention because Steven Spielberg announced he’s making a film based on it. Work on it has been delayed, but I hope it goes ahead.

What did you want to illuminate with The Pope Who Would Be King? The story of the Roman revolution of 1848 is curious. It was so important historically—to the church, to the history of Italy, to the history of Europe. Yet the last book in English on it was published in 1907. It was the French army that reconquered Rome for the pope and reinstalled a theocracy—ironic because France, too, had recently become a republic.

What kinds of lessons can we draw from what happened during this period that can apply to today? The battle between church and state continues to be waged in many ways. Some feel that the church should adapt to modern times, but others believe that the church is the champion of eternal verities, and we can’t accept gay marriage or have equal rights for women in the church.

In the acknowledgements of your new book, you talk about the effects of technology on research. Historians today have incredible advantages. Just take Google trying to digitize all the books ever published. Now, for 19th-century publications, where you don’t have copyright issues, I can go online, as I did for this book, and look up hundreds of memoirs and other kinds of primary sources and just download them.

Do you still have history to mine from this period? Since I finished this book, I have been working on a follow-up to my previous book, The Pope and Mussolini. That book told the story of the decision of the pope to make an alliance with the fascist regime. And now I’m looking at the years of World War II—the very dramatic period of the relationship of the pope and the Vatican to the Italian fascist regime during the war. I’ve already gathered thousands of documents from Italian, French, British, German, and American archives. What’s not yet open are the Vatican archives for that papacy, so that’s a bit of a challenge.

(This interview has been edited and compressed for length and clarity.)