Language and Plague

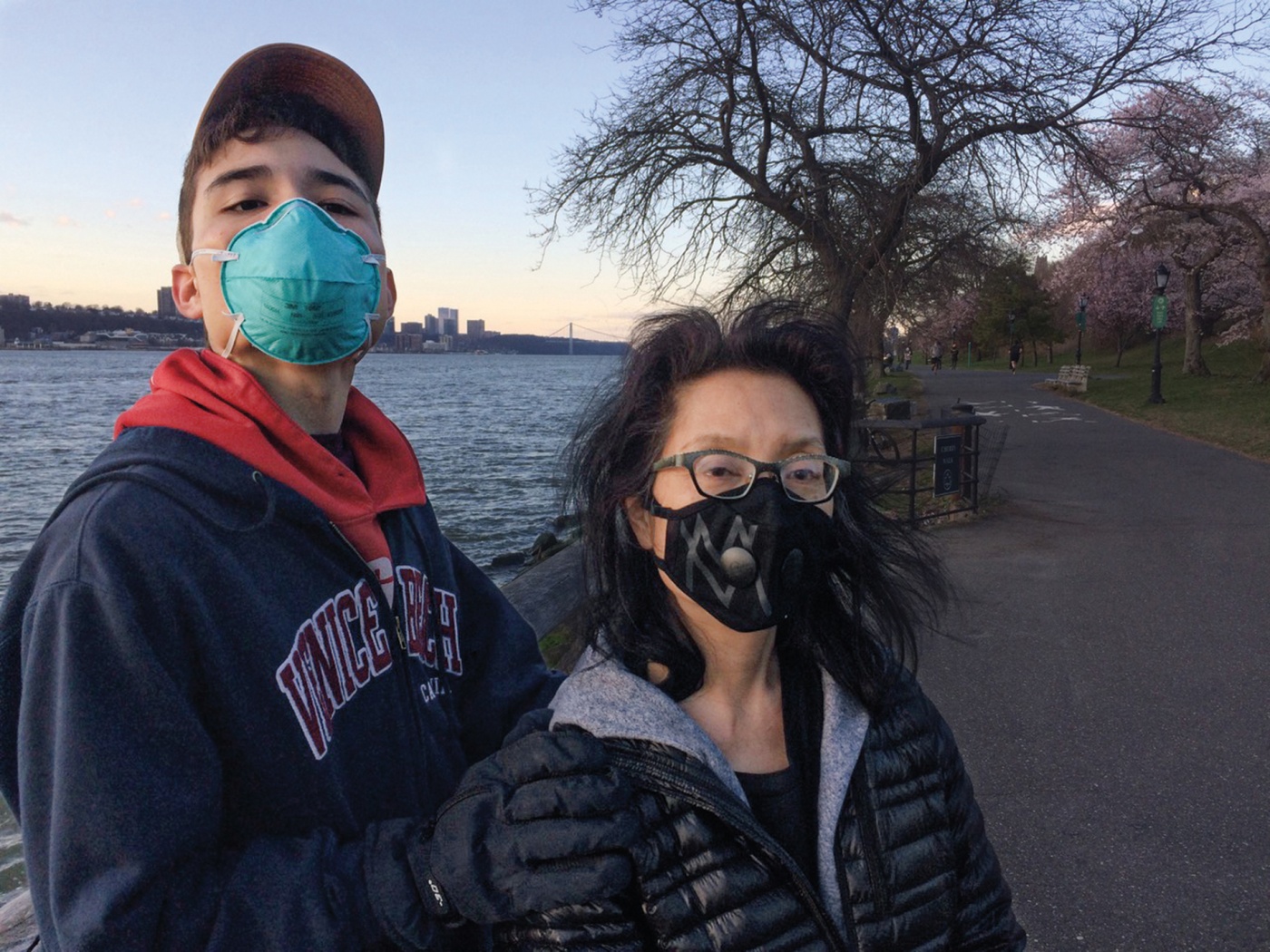

In locked-down NYC, with a feverish son, Marie Myung-Ok Lee ’86 considers COVID-19 and Camus

March 28, 2020: My son spikes a fever just as I am trying to puzzle out an email to my college students, whom I’ll soon meet for the first time since this pandemic lockdown happened in New York City, as pixelated faces on my computer screen.

In the mainstream media, the news seems to be that Manhattan has turned into some Mad Max-ish hellhole of contagion. In Rhode Island, where we used to live when my husband and I both went to and taught at Brown, the governor has commandeered the National Guard not only to stop cars with New York plates, but to literally hunt down New Yorkers, door-to-door, to make sure they’re quarantining.

However, inside our apartment, it feels abnormally quiet. In New York City, it’s abnormal to hear the spring call of birds instead of the usual cars, squealing bus brakes, bicyclists and drivers blasting rap, música ranchera, soca, jazz. We live near a daycare and every day at 4 p.m. I normally hear the wails of a child going through her terrible twos. Now, it’s silence except for the wails of sirens, near and far, the occasional chop-chop-chop of helicopters, and the church bells, which used to blend with the background noise and now become a primary marker of the day. Inside, our apartment building is quiet, almost cozy. No sounds of doors, of the elevator. The lobby, which used to be like Grand Central as we waited with our son for his school pickup with others also waiting for their rides, with professors rushing to their 9 a.m. classes, dogs and their humans going out for a jog, is now empty; it smells like food all the time because we are all here, instead of rushing along our busy lives. We are all here, even though we can’t see each other, living, each behind our own doors.

That I can still smell the varieties of food—sweet baking, kimchi, coffee, roasted meat—is always a relief, as the newest symptom doctors are alerting us to suggests the virus interferes with neurological wiring, causing olfactory dysfunction. Because my son has intellectual disability and various autoimmune issues that contribute to his physical and mental discomfort, my husband and I are exceedingly vigilant that he not get this. He does not have the language capacity to tell us if he feels bad, can’t smell, has pain. A smallish comfort, we have been on lockdown for more than 14 days with absolutely no contact with anyone, but still our son, after urinating in his bed with anxiety, on a beautiful spring day violently throws up. The next day, he wakes feeling hot, and we confirm: fever.

We already know, from watching the news, that paramedics are overwhelmed in the city, that if you call 911, you might get a busy signal. Dispatchers are having to literally make medical life or death decisions now: is congestive heart failure worth an ambulance over a possible symptomatic COVID case, or not? While I’m getting in touch with his pediatrician about what to do if his symptoms become acute, my cousin calls to tell me that her whole family was stricken with COVID-19, from her job as a nurse, and her husband is in the ICU, in a medically induced coma and on a ventilator, fighting for his life.

When there was a fire at a dorm near our apartment a few years back, the college brought in a temporary boiler, contained in the back of a semi-truck, which was parked, hulking, on the street. It connected to the smoke-smudged building by wide industrial black hoses, and chuffed along until the boiler was repaired, then things got back to normal. Now, in the news we see pictures of similar trucks parked and connected umbilically to hospitals: temporary morgues to keep the bodies of the dead, which are starting to pile up.

I can’t help harking back to my undergrad days, reading Camus’ 1947 novel The Plague for a Religious Studies class that was called something like Religion, Literature, and Society. And not because of the uncanny echoes of the way this pandemic has unfolded—ignoring the warnings, the skeptical doctors calling the other ones “alarmist,” the diddling pols, the drastic quarantine of Oran, which might as well be New York City—but because the book, like Camus did frequently in his own diaristic writings, urges an almost gentle and persistent question: how do you want to live?

We already know too much about the people responding in fear, including the false bravado of politicians who endanger others by downplaying the danger. Now that the virus has encroached into my family, unbidden, heedless of how my cousin’s humanitarian profession as a nurse was what brought it in, I’m allowing myself to feel terror, but take after Rieux, the doctor who sounds the early alarm about the plague, and Tarrou, the diarist chronicling it.

The only way to fight the plague is with decency, Rieux says, and defines it as “doing my job.” The job of decency makes the “right” thing to do easy and clear. Many institutions have already let us down or perhaps don’t have the capacity to care, but our older neighbors, as we thought to check on them, loaded us up with food, spirits, even loaned us an extra apartment for a quiet place to do our online teaching. In our neighborhood, I see signs everywhere, people volunteering to help needy strangers—the disabled, the elderly—shop during the quarantine; when I talk to my cousin in California, I can hear her doorbell ringing—people bringing food and comfort, and I am relieved. Not of my terror, but of that pathological black fear, America’s dark heart, the racism, the hoarding, the deliberate refusal to self-isolate, and all I can do is keep doing my job, first and foremost, to be decent to fellow humans.

My son, with his limited communication, has a favorite phrase about jobs: “It’s Mommy’s job to keep me safe.” He speaks echolalically, i.e., echoing other things he’s heard, and I have no idea where he’s picked this up, but it is more important to me now than ever.

Writing is also my job. Words seem a flimsy thing compared to Dr. Rieux’s quest for the lifesaving “serum” or more ventilators or epidemiological research, but writing and witness, Camus reminds us, are also moral acts. Writing shows us that what we think is new and fantastical is just that sinister part of human nature, presaging the current administration’s slick manipulation of labeling a “China virus” to deliberately incite racist violence against Asians; its call for people to die to save the economy: “I’d heard such quantities of arguments, which very nearly turned my head,” says Tarrou, the writer. “And turned other people’s heads enough to make them approve of murder, and I’d come to realize all of our troubles spring from our failure to use plain, clear-cut language.”

Language might even be more important, because the lifesaving serum of today is only for today and not for the next plague, or war: “It could only be the record of what had to be done and what, no doubt, would have to be done again against this terror,” Tarrou says. Because as we came to learn in the class, Camus is not talking about an actual virus, he’s talking about the human condition, where “stupidity has a way of getting its way” and the only antidote is straightforward decency in act and truth in language. “This” will certainly come again—what will we do with this vital emergency that is not death, but life?