Under the Hood

The descendant of a Klansman probes the racial violence in his family background to expose larger truths about the history of white America.

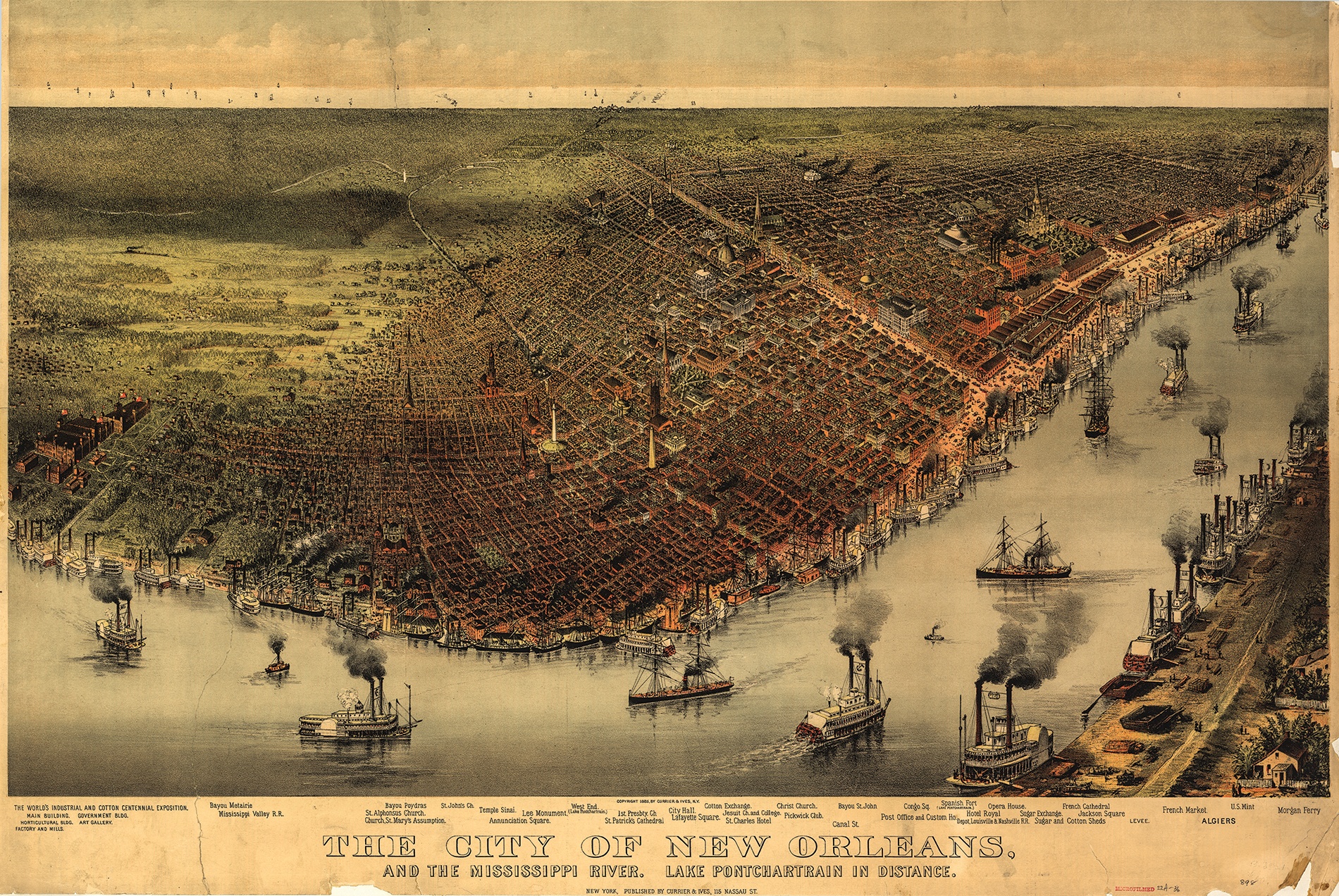

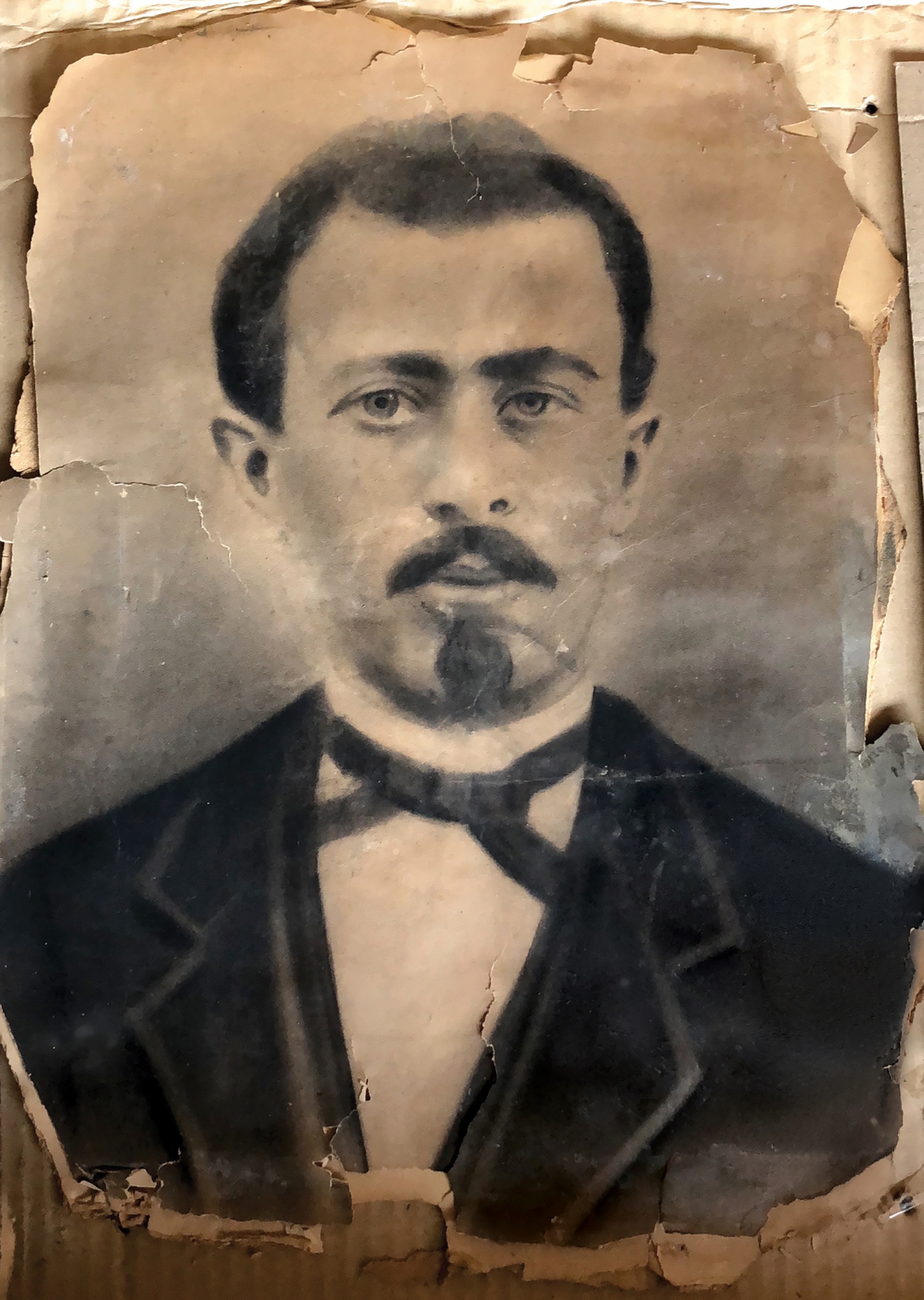

Edward Ball ’82 grew up in New Orleans hearing occasional anecdotes about “our Klansman.” Ball’s maternal great-great-grandfather Polycarp Constant Lecorgne, named for a Catholic saint, was a Confederate veteran and a carpenter. He owned slaves and later joined white militias. To Ball’s great-aunt Maud, the Lecorgne family historian, he was a heroic “redeemer” who played a bit part in the Southern drama of overthrowing Reconstruction.

After his mother’s death, in 2003, Ball inherited Maud’s notes—and the Klansman’s story, intriguing but still skeletal. Several years later, he tried, and failed, to imagine it as fiction. He eventually turned to historical archives, producing his sixth work of nonfiction. Like his groundbreaking Slaves in the Family, published more than two decades ago, Life of a Klansman: A Family History in White Supremacy, which appeared in August to strong reviews, seeks to exhume not just one family’s shameful secrets, but America’s.

However coincidental the book’s timing, its themes have struck a nerve. “[A] story for our cultural moment,” the author and essayist W. Ralph Eubanks declared in the Wall Street Journal. “The interconnected strands of race and history give Ball’s entrancing stories a Faulknerian resonance,” the historian Walter Isaacson wrote in the New York Times.

Ball’s unlikely New Orleans–based protagonist, a man of modest means and abilities, plunged into the turbulent currents of the Reconstruction era with its warring ideologies, political upheavals, terror campaigns, and street fights. That history, much of it now little known or taught, has its own allure. Ball insists on its present-day relevance: The nineteenth century’s embrace of white domination is a marker of America’s continuing obsession with “whiteness,” he suggests, and foreshadows our own racially polarized culture and politics.

“What I wanted to do, and simultaneously was afraid to do, was take ownership of white supremacy—acknowledge that it is a part of my family history and, by implication, part of me. So that was frightening,” Ball says over lunch earlier this year at the Union League Cafe in New Haven, Connecticut. “And yet I felt that to do that—to own white supremacy—was an important act.”

The point, Ball says, isn’t that he has an avowed white supremacist (actually several, including cousins) among his ancestors—it’s that millions of other Americans do, whether they realize it or not. Life of a Klansman attests that “this happened, this is not only my family, but part of our national history—and not an uncommon part. The story is that white supremacy is deep in American life, it is long lived, and it is normal.”

The Black Lives Matter protests of the police killing of George Floyd, which occurred after our initial interview, spotlight the prescience of Ball’s undertaking. “This year, despite its shadows, has been hopeful. This year, a movement arrived: the mass marches, talk of systemic racism, the statues of successful racists tumbling down,” Ball says. “Since 2016, a river of racism flowing from Washington has submerged us, but now there seems to be a levee going up against the stream.”

Malevolent memorabilia

Nestled among the soaring spires and ornate facades of Yale University’s neo-Gothic campus, the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library is itself a rarity: a squat, windowless Modernist building clad in white marble and granite. Ball, curly-haired and lanky in a black wool suit jacket and navy sweater, his Southern accent long since “sanded away,” seems at home here. For five years, he was a part-time lecturer at Yale, teaching writing and American studies. He left the adjunct position in 2016 to concentrate on Klansman, logging many hours in archives like this.

In a library study room, he thumbs through Klan-related memorabilia, including sheet music for a romantic ballad celebrating the Klan. The archaic Victorian lyrics for “Midnight’s Roll Call,” dating from 1868, mask the grotesque deeds the song trumpets. “It’s a ballad of a night ride against a Black village” that “would be played in the parlors of a ‘good’ white family,” Ball says.

Equally chilling is a Klan fashion catalog, displaying white robes, with diversely colored insignia and scarves, for women of different ranks. Some have short skirts, the Klan equivalent of flapper dress. The booklet dates from the 1920s, when a reinvigorated Klan attracted an estimated five million members nationwide. Consigned in the 19th century to making their men’s robes, women in the ’20s were “coming out from the sewing rooms and onto the streets,” says Ball. “The liberation of [white] women included this.”

One primary source Ball used for Life of a Klansman is an 1884 history by two former Klansmen. “They’re looking back and telling their story with a great deal of romance and self-congratulation,” says Ball. “Remember: They won.” In the 1870s, Reconstruction in the South ended and the era of Jim Crow began. Polycarp Constant Lecorgne (1832-1886) played a minor role in that triumph of white supremacy.

But telling that story would prove a challenge.

For Slaves in the Family, Ball could draw on a rich trove of papers, from letters to slave lists, that his father’s forebears, wealthy rice planters in South Carolina, had preserved. The Ball papers, along with other documents and artifacts, also informed two of his subsequent books: The Sweet Hell Inside, a multigenerational chronicle of the mixed-race Harleston family (distant cousins of his), and The Genetic Strand, Ball’s attempt to resolve family mysteries by DNA-testing locks of his ancestors’ hair.

In Lecorgne’s case, however, the evidence was sparse. To reconstruct his great-great-grandfather’s life, Ball started with his great-aunt’s stories, along with genealogical information from Catholic Church records. But he found no Lecorgne letters, diaries, or other first-person sources—the gold standard for biographers.

Imagining his ancestor’s missing voice, he attempted a novel titled Memoir of a Klansman. But after 100 “mediocre” pages, he abandoned the effort. He settled on a hybrid form: Other historians, writing about women, Blacks, and the working class, were demonstrating the potential of combining indirect or unconventional evidence with informed speculation. Ball’s models included Jill Lepore (Book of Ages), Daniel J. Sharfstein (The Invisible Line), and Saidiya Hartman (Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments).

Ball’s book—like Lepore’s, on Benjamin Franklin’s sister Jane—is a “microhistory,” chronicling an individual whose deeds might seem unworthy of a full-length recounting. But “a single life carries a society in microcosm,” Ball explains in his prologue.

“To take ownership of white supremacy—acknowledge that it is part of my family history and, by implication, part of me—was frightening.”

One task was to tease out the links between Lecorgne and the white supremacist groups that flourished in southern Louisiana after the Civil War. While known collectively as the “Ku-klux,” these primarily French Catholic organizations had other names and morphed over time: the Knights of the White Camellia, the McEnery Militia, and the White League. Ball pinned down Lecorgne’s membership in the latter two groups and infers his membership in the more secretive Knights, whose founder was a family friend.

From the available evidence, Ball believes—but can’t prove—that Lecorgne participated in the 1866 Mechanics Institute Massacre in New Orleans, a deadly white uprising against Black political rights. An arrest record and indictment do clearly indicate his involvement in the McEnery Militia’s capture of a police station in 1873. The charges against him, for treason and violating the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, were dismissed, Ball says, by a sympathetic judge.

When Ball began his research five years ago, “before Trump, before the [publicized] rash of white supremacist murders,” some friends advised him not to bother. They suggested his concerns with the legacy of “whiteness” were outmoded in the “post-racial” era signaled by Barack Obama’s presidency. Ball parted with his literary agent of 15 years when she told him the subject was “too radioactive” and “had a deplorable protagonist.” Another agent signed on, then backed out, saying, “I don’t want to make a hero for white supremacists.”

Ball persisted. In 2017, he retained Andrew Wylie, an agent known for his high-powered literary clientele and clout. Shortly afterward, Ball received four offers for the book. He chose Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which had published Slaves in the Family.

Uncomfortable truths

“One thread that weaves through my books is that I do family history as a way to access History, with a capital H,” Ball says. “Family history is full of drama, and it opens a door directly to politics.”

Ball’s immediate family endured its own private dramas. His father, Theodore Porter Ball, was an Episcopal minister who kept changing congregations. “We moved around,” he says, from Georgia to Florida to Charleston, South Carolina. “He seemed to have a restless side to him because he would request another church assignment every three years or so.”

Ball remembers his childhood in the late 1960s and ’70s as “entirely segregated,” as though an “iron curtain” separated Blacks and whites.

After the recurrence of a brain tumor, his father, unable to work, committed suicide. “It broke our family,” says Ball, who was 12 at the time. “It broke my childhood into two parts, before and after his death, and decimated our sense of who we were.”

Ball’s mother, Janet Rowley Ball, moved the family—Ball and his brother Ted, two years older—back to her native New Orleans. She “wanted to be with her people,” he says. “It helped.” The family lived modestly on her earnings as a bookkeeper.

Scholarships and loans enabled Ball to attend Brown, where he studied history and planned to become a lawyer. “I wanted to be a part of the Ivy League gentry,” he says. But he wasn’t happy and after two years took a leave. “I think I had the restlessness that my dad had,” he says.

He worked as a waiter in New Orleans, spent a year hitchhiking in Europe, then returned to Brown and concentrated in semiotics, studying film and mass media. Next came a master’s in film at the University of Iowa. He decided that the life of an academic was not for him and moved to New York, working as a proofreader while trying, unsuccessfully, to land a job in advertising. “It was only at age 26 or 27 that I started to publish anything,” he says. He wrote freelance film, art, and book reviews, as well as an architecture column for the Village Voice.

At 34, he began researching Slaves in the Family, “a story that’s Black and white simultaneously, a common history.” Ball tracked down descendants of workers who’d been enslaved by his plantation-owning ancestors, seeking racial reconciliation. Some, he found, were his cousins, the products of sexual violence and more complex relationships that included long-term partnerships or even common-law marriages. Ball’s mélange of history, journalism, and memoir won the National Book Award. Since its 1998 publication, he says, “the desire to reckon with the hard parts of the past… has become much more acceptable.”

“Our country was founded on race violence, which was more important than religious liberty, more important than the free market.”

Overdue reckonings

Even before the protests following George Floyd’s death, the zeitgeist seemed ready for Klansman. Across the street from our lunch at the Union League Cafe, the Yale University Art Gallery was hosting the traveling exhibition Reckoning With “The Incident”: John Wilson’s Studies for a Lynching Mural. The centerpiece was a silk-screened photograph of a 1952 fresco mural, no longer in existence, by the Massachusetts-born African American artist. Against the backdrop of a burning cross, white-robed and masked Klansmen have cut down an African American hanging victim. Looking on, through a window, another Black man holds a shotgun, while a woman embracing a child cowers in fear. The scene is spatially compressed and stylized, with few identifying details; the action could be happening anytime, anywhere.

The mural, Ball says, testifies to “the uncomfortable, unspeakable parts of American life.” As Ball sees it, “Violent white supremacy is like an underground river, until it erupts like a geyser. And that’s a moment we’re in right now. We might think that it’s aberrant, exceptional, but it’s not.” The reckoning, in his view, is overdue.

“Our country was founded on race violence, which was more important than religious liberty, more important than the free market,” he says. “Race violence is in the DNA of American identity. And white people in general, not merely the families of Klansmen, are heirs to and beneficiaries of white supremacists and their terror campaigns.”

In the case of his great-great-grandfather, Ball says he felt some empathy—“oscillating with disgust and shame”—for his “often pitiful life,” which included unemployment, financial hardship, and the loss of five of his nine children before they reached adulthood.

Ball sought out the descendants of people—in this case, from New Orleans’s Black and mixed-race communities—who might have been affected by his ancestor’s actions. The meetings, he says, constituted an “unusual and very cathartic moment”—“as though a door of the past had been flung open and a ghost comes out and presents himself.”

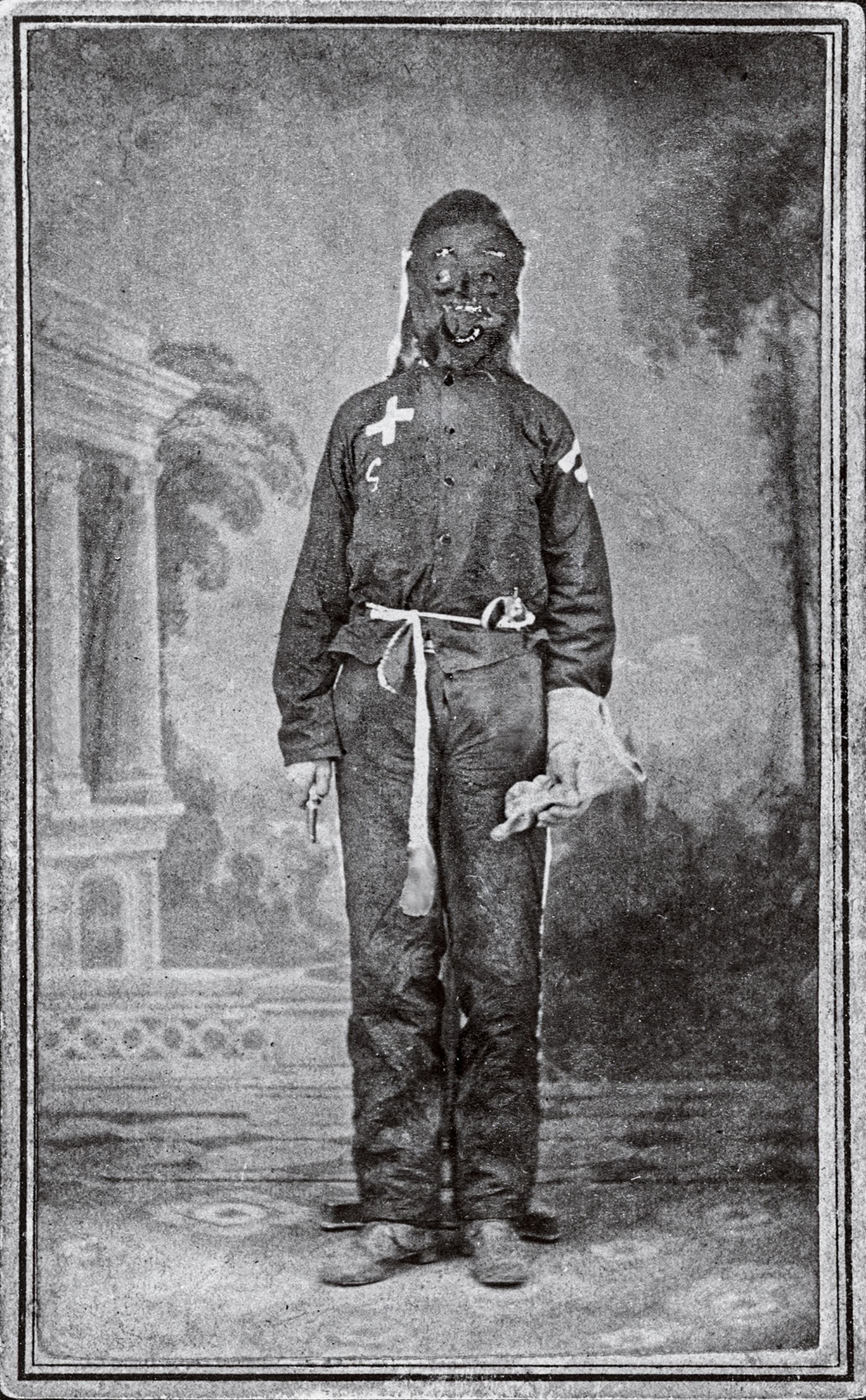

One door Ball knocked on belonged to Janel Santiago Marsalis, an 84-year-old artist and retired art teacher in New Orleans who is the great-granddaughter of Alfred Capla (pronounced Kah-PLAH). Capla, a “Creole of color,” was partially blinded after being shot in the eye during the Mechanics Institute Massacre in which Ball’s Klansman may have participated.

When she first met Ball, who showed up unannounced, Marsalis was skeptical. She declined to invite him in. “I didn’t know what kind of game he was playing,” she says. “I didn’t know if he had something dishonest in mind.”

Paging through Ball’s book The Sweet Hell Inside, one of whose characters is an artist, reassured her, and a series of coffee shop meetings involving other family members forged a bond. Though Ball’s heritage was “disturbing,” Marsalis says, “he did seem to be genuinely regretful and embarrassed that he was a descendant of somebody who would have taken part in a gang action. We still feel strongly about the Klan. [But] he presented himself in such a way that we felt a bit of closeness to him, and we felt a bit of joy that he was interested in what happened then, and to our family, and at the prospect that our story would be in a book.”

Can such individual encounters really help heal racial rifts so deeply embedded in American history? “It’s painstaking,” Ball acknowledges. “It’s not something that can be scaled up.” He hopes Life of a Klansman will stand as “a countervailing discourse to the triumph of white supremacy”—a means of “taking honest responsibility for the dark parts of our national identity.” In an era “when whiteness and white supremacy have become more powerful and menacing,” Ball says, “I would like the book to be a voice of protest.”

Julia M. Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Mother Jones, The Nation, Slate, and many other publications. @JuliaMKlein.