Decoding Digital Minds to Understand Our Own

AI in mental health care could go very wrong. That’s why researchers are prioritizing it.

Can a machine ever truly understand a human? It has been the subject of philosophical debate for decades. But since the release of ChatGPT in 2022, it has become an urgent, practical question as millions have started to use AI assistants for everything from homework help to emotional support.

The stakes are very high. Last April, a 16-year-old in California was found dead by suicide. His father discovered that ChatGPT had offered to help the boy write a suicide note and dissuaded him from communicating with his parents about his distress. In August, the boy’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit.

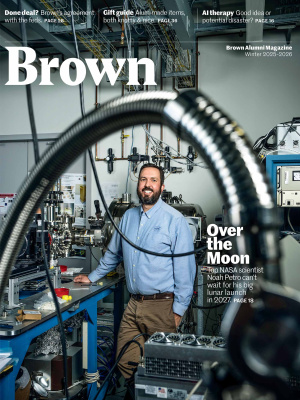

Earlier this year, a team at Brown landed a $20 million grant to launch ARIA, a national AI institute that will develop trustworthy AI assistants, starting with mental health applications. The foundation for this ambitious project was laid years ago by researchers asking fundamental questions about the nature of intelligence in humans and machines.

Does AI even understand what it’s saying?

Ellie Pavlick, a distinguished associate professor of computer science, spends her days trying to crack one of AI’s most perplexing puzzles: Do machines actually understand the words they use, or are they just very sophisticated mimics? In addition to being the inaugural director of ARIA, Pavlick works as a research scientist at Google DeepMind and leads a Brown lab that probes how both humans and AI systems make sense of language. It’s detective work that requires equal parts computer science, philosophy, and cognitive science, a combination that makes her something of an anomaly in a field often dominated by pure technologists.

Pavlick’s unconventional path to AI research began with undergraduate degrees in economics and saxophone performance before pursuing a PhD in computer science. That multidisciplinary background shapes her approach to one of AI’s most fundamental questions: whether machines trained entirely on text can develop genuine understanding. “Words like intelligence, understanding, and thinking are being used to describe AI, but no one actually knows what they mean,” Pavlick says. Her team is working to change that.

For example, in one of Pavlick’s studies, she and a colleague tested whether AI trained only on text could understand real-world concepts like directions and colors. Surprisingly, after showing GPT-3 just a few examples of what left means in a simple grid, it could figure out what right means on its own, suggesting these systems might grasp spatial relationships despite never experiencing physical space.

This research is an example of one way to scientifically study the idea of “grounding,” a concept from philosophy and linguistics that asks whether the meaning of words depends on connections to the physical world, sensory experiences, or social interactions.

“What it means for a non-human system to have human-

like understanding is as much a humanistic question as a scientific one,” says Pavlick. “A lot of people working in AI shy away from big philosophical questions because they sound outside the realm of what they can comfortably study, but these are exactly the questions we need to tackle.”

Can AI be taught human values?

In 2021, Suresh Venkatasubramanian spent his first year as a Brown professor of data science and computer science not on College Hill, but at the White House. A Biden appointee, he was there to help craft the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, a framework for protecting civil liberties in the age of AI.

Venkatasubramanian, who has done a decade of research into how automated systems can perpetuate discrimination, sees an urgent need for a more value-centered approach to designing these systems. “We’re beginning to see examples of how people can be seriously harmed by interactions with chatbots,” he says. “There’s a mismatch between the speed of deployment of AI assistants and our understanding of them. We need to catch up before widespread adoption continues.”

Venkatasubramanian has developed new approaches to algorithm design by starting with the perspectives of those affected by automated systems. His current research tackles the challenge of “alignment,” which is all about creating AI systems that operate according to human values.

Do humans and AI learn in similar ways?

In Michael Frank’s lab, two types of neural networks operate side by side: the biological kind found in human brains and the artificial kind powering today’s AI. Frank, director of Brown’s Center for Computational Brain Science, has spent two decades exploring whether these seemingly completely different systems share fundamental principles of learning.

Frank’s research has revealed both surprising parallels and crucial differences between biological and artificial learning. For example, both AI and humans learn by adjusting connections between neurons (or their artificial equivalent) based on experience, but the mechanisms diverge in ways that may explain the unique flexibility of human intelligence. “The mathematical algorithm says, ‘Here’s how I can adjust all the connections in the whole network,’” Frank says. But biological neurons “can’t possibly know what’s happening in all the other neurons in the brain.”

In early 2025, Frank published a paper in collaboration with Pavlick that showed that both humans and AI systems use two complementary learning strategies: rapid learning that allows quick adaptation to new rules (like figuring out a board game after a few examples) and slower learning that builds skills through repetition (like practicing piano). The study also revealed the same trade-off in both systems: the harder a task is to complete correctly, the more likely it will be remembered long-term.

Understanding these similarities and differences, Frank says, “will be important to ultimately developing better AI systems.”