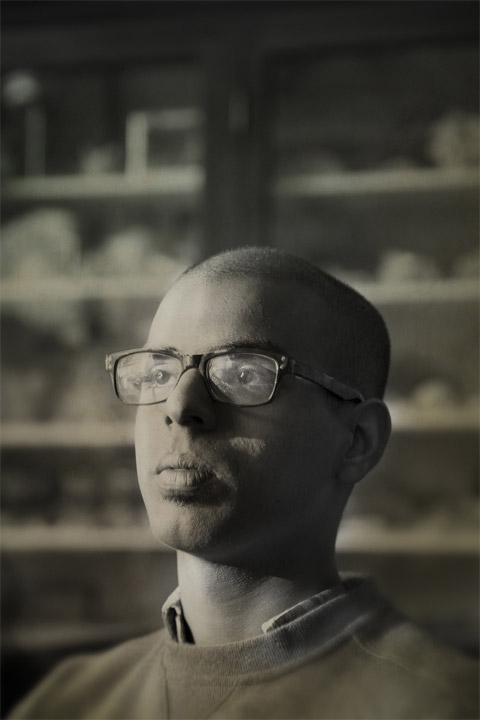

Pathikrit "Po" Bhattacharyya grew up in Calcutta, the son of doctors. Because of his broad intellectual curiosity in high school, when it came time for college he had trouble focusing on a single subject. He chose Brown, he says, for its flexible curriculum. “I liked far too many subjects in high school,” he explains, “and I had no way of picking one or the other.”

“I’ve seldom seen a human being treat another human being as poorly as that,” Bhattacharyya says. He still regrets how he reacted that day. “I froze up and didn’t leave my seat,” he says. “I didn’t know what to do.”

At Brown, Bhattacharyya became fascinated with jellyfish, especially a long and stringy type called siphonophores. With bud-like structures coming off either side of what’s known as the central stem, siphonophores, most of which swim throughout the water column, can grow to 120 feet, making them the longest animals in the world. To capture prey, they shoot small, hollow harpoons filled with immobilizing toxins.

But what really fascinates Bhattacharyya about siphonophores is that they are actually dozens of individual animals, called zooids, joined together. The zooids act as a colony, with each class of zooid carrying out a function for the larger group. In a 2009 paper, Brown evolutionary biology professor Casey Dunn, with whom Bhattacharyya studied, described siphonophores as “thousands of conjoined twins…, some with only legs to move everybody, others with only mouths to ingest food, others with enlarged hearts to circulate the shared blood, and others fully dedicated to the sexual production of new offspring colonies.”

In his senior year, Bhattacharyya received a Royce Fellowship to study siphonophores. He traveled to Villefranche-sur-Mer outside Nice in southern France, where the animals live in abundance and can easily be collected. Bhattacharyya brought several specimens back to Brown with him and studied their nervous systems. Amazingly, there is no central brain controlling and organizing the zooids. They are believed to communicate with each other by passing messages along the nerve cells running down the central stem. “They have the most advanced nervous system in the animal kingdom,” Bhattacharyya says. He used existing research on the siphonophores’ genes to map out the animals’ nervous system.

But Bhattacharyya is too restless to stick with jellyfish. Next year he

plans to work for the educational technology company IXL Learning in

San Mateo, California, and he eventually hopes to return to India and

start K–12 schools with an American-style liberal arts curriculum.