Angelique Brunner ’94 is a driving force behind the revitalization of some of Washington’s most blighted neighborhoods. Combining principles and profit, the former venture capitalist is leveraging a controversial visa program for foreign investors.

In a white hard-hat and a fluorescent yellow safety jacket, Angelique Brunner ’94 strides around tall stacks of drywall sheets and through muddy puddles that in just a few more months will be transformed into her new thirteenth-floor apartment. It sits atop the under-construction Highline residential and retail complex in Washington, the latest venture underwritten by her firm, EB5 Capital. At a window taped over with a large “X,” with the U.S. Capitol dome clear in the distance, she pauses to show off what pleases her most about the view from her future D.C. digs.

“So we’re right here, this is our project, and across the street where we parked, that’s us,” says Brunner, gesturing out the window at the blocks directly below the construction site, just northwest of Union Station. “The parking lot next to it is us—there are all apartments going up. And that arch is REI”—the trendy outdoor store in an abandoned former theatre, also an EB5 Capital project.

Just behind the construction site is a large Hampton Inn that Brunner’s EB5 Capital financed when this D.C. neighborhood hadn’t earned its trendy name of NoMa (north of Massachusetts Avenue) but was instead a no-man’s land that was home to an aging storage facility where Brunner kept some of her things when she moved to the nation’s capital in 1999.

“My mom used to write me notes so I could get out of school and protest at Berkeley,” Brunner recalls.

Today, the 46-year-old Brunner’s move from storage locker to penthouse and her firm’s role in making that happen form the outline for an all-American success story—not just because of the roughly 30,000 new jobs EB5 Capital takes credit for, from D.C. to Portland, but also because of Brunner’s ability to thrive as a gay black woman in a male-dominated world of developers and financiers.

There’d almost have to be a catch—and to a chorus of critics, there is. Brunner’s company funds projects through the government’s EB-5 visa program, jumping foreigners seeking permanent U.S. resident status, or a green card, to the head of the line after they invest in projects intended to create jobs in low-income neighborhoods. Naysayers call it “citizenship for sale”—and that was before President Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner was linked to the program.

Entrepreneurs seeking to defend EB-5 have made Brunner their spokeswoman and the public face of the program. That’s not surprising given her unblemished record, her stereotype-busting background, and her trademark self-assurance as she insists the visa-waiver program is creating good middle-class jobs for Americans. What is remarkable about Brunner’s high-profile platform is some of the hurdles she had to leap to get there.

Almost derailed

“I can’t come back to school.”

Angel Brunner was just three credits away from her Brown degree in public policy in the winter of 1994 when she picked up the phone and uttered those words to the then-dean of the college Lydia English. Brunner’s mom had just died suddenly of a heart attack. Her much-older dad was ill, and her 8-year-old brother, Paul, was already struggling in school. She insisted to the dean that she’d have to drop out to deal with the crisis back home on the West Coast.

Falling short of completion at Brown would have been a stunning failure for a 22-year-old who’d given no evidence of even understanding the concept of failure after seventh grade, when her martial arts teacher—she’d been studying since she was 6—insisted she fight only bigger boys. That was also the year when, based on an offhand suggestion by some adults she knew, she set her sights on escaping her apartment complex in the working-class San Francisco suburb of San Mateo for a place 3,000 miles away called Brown University.

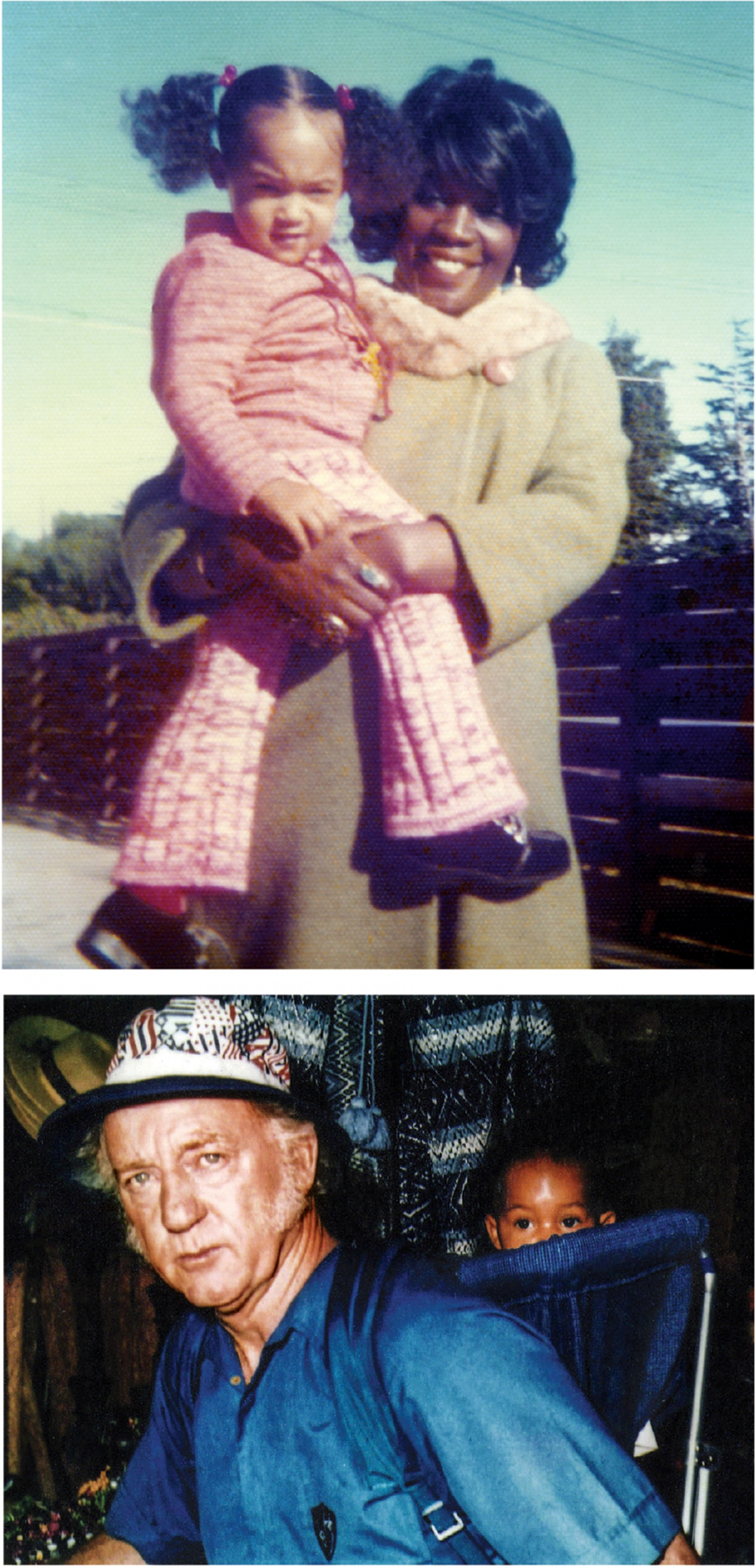

Brunner credits a lot of her youthful moxie to her parents. Her dad was an independent-minded Pennsylvania farm kid, a son of German immigrants. He married Brunner’s mom, whose roots were on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, after they’d met at a Lena Horne concert. They had to go to Nevada to tie the knot because interracial marriage was legal there. As parents, Brunner said, they taught their daughter strong values—but didn’t impose many rules.

“My mom used to write me notes so I could get out of school and protest at Berkeley,” Brunner recalls. She held onto that after earning a scholarship to attend Brown. When protesters seeking a need-blind admissions policy took over University Hall in April 1992, Brunner, one of the leaders, was manning the barricades, directing 253 students onto buses as they were arrested.

“I figured out what my purpose was, and my purpose was to impact the most people in a positive way.”

“Angel always ends up in leadership roles. It’s in her nature,” says Jenny Rogers ’93, a Brown classmate who also took part in the 1992 protests and today, as director of arts and recreation for Mill Valley, California, continues to stay in touch. “She’s very passionate about the things she cares about”—a straight line, Rogers says, from campus protests to urban renewal.

But with the sudden blow of her mom’s death, Brunner thought the Brown administration might remember her as a troublemaker. Instead, Dean English bought her a plane ticket home and the University improvised a plan for the senior to bring her dad and brother back to Providence, find an apartment, and enroll Paul in a local grade school while allowing her to take just two courses a semester so she could manage everything.

“Now remember the last time I was on campus, I got 253 students arrested,” Brunner says. “I am not an unknown quantity. And I am not necessarily famous for the right reasons.” She today credits Brown for that life-altering decision, but that didn’t mean her new life was going to be easy.

She says she struggled to find a College Hill–area landlord who’d rent a student-type apartment to a biracial family until she sent her then-girlfriend, who is white, out to make the first contact. Her dad, who was in his early 70s, died little more than a year after Brunner’s mom, leaving Brunner as a single parent to her brother, for whom getting the right special education was an ongoing struggle. Despite those obstacles, Brunner not only graduated Brown but received a similar helping hand from administrators at Princeton, who re-admitted Brunner to a graduate program after she’d initially rejected them for Berkeley, only to learn there were better schools for her brother in New Jersey.

“There’s nothing cookie-cutter about her,” reflects John Templeton, the recently retired Princeton admissions officer who moved mountains that fall to get Brunner re-admitted to the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, after he’d met her during a summer program.

But Brunner’s eventful time at Brown hadn’t been her only takeaway from Providence. She also joined the first cohort of AmeriCorps—the public-service program created under President Bill Clinton—and her work in South Providence with a community development group called SWAP (Stop Wasting Abandoned Properties) that rebuilt crumbling homes and offered credit counseling for an immigrant-heavy client base planted seeds for Brunner’s later rebirth as an EB-5 entrepreneur.

Always Moving

Today, Brunner says she never stopped looking for ways to carry out the goals she set for herself in the seventh grade. “I figured out what my purpose was, and my purpose was to impact the most people in a positive way,” she says. She didn’t quite find that during a brief stint in venture capital, the job that brought her to D.C. at the end of the 1990s, where a boss complained about her hard-charging “pace”—the same complaint she heard during a brief stint with Fannie Mae, the government-sponsored backer of mortgages.

Meanwhile, Brunner was both troubled by the dilapidated state of Washington’s neighborhoods and puzzled by the excuses. “In 2000, we had no Target, no Home Depot, and no Whole Foods, and people were still telling me about the 1968 riots” that burned after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination. The inertia on jobs and housing still weighed on Brunner’s mind a few years later when an immigration lawyer who was a friend of a friend told her about the government’s then-obscure EB-5 Immigrant Investor Visa Program.

Congress had authorized EB-5 in 1990, first for foreign entrepreneurs to work within the United States. It later evolved to allow passive investors of $500,000 or more to apply for green cards and resident status. The program foundered for more than a decade, from both less-than-expected use and several allegations of fraud. Then the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees immigration, made changes to make it more attractive for foreigners and American entrepreneurs who set up “regional centers” to connect visa seekers with developers needing capital. Brunner saw opportunity.

When someone presses Brunner on gentrification, she counters with, “What’s your plan for bringing jobs to the neighborhood?”

In addition to NoMa and elsewhere in D.C., EB5 Capital, the firm Brunner eventually founded, runs regional centers and supports projects across the country, including a luxurious 36-story Ritz-Carlton in midtown Manhattan. Its claim of 30,000 new jobs includes construction as well as retail and hotel positions.

Brunner is expounding on all this as she stands on Fourteenth Street in Washington, in front of a gaping hole that once was a Safeway serving a largely low-income clientele not far from the U.S. Capitol. Her Beckert’s Park project there will include 300 apartment units—most high-end, but 14 percent as affordable housing—and feature a brand-new, 60,000-square-foot Safeway, providing jobs for the neighborhood and ensuring it won’t become a food desert.

“If you talk to any of my developers, they’ll say, ‘If not for the EB-5 money, I wouldn’t have built the project,’” Brunner says, as a payloader operating just behind her beeps away. Since the 2008 financial crisis, she explains, banks will offer loans in emerging neighborhoods, but not the full amount. Money from the foreign visa seekers fills the gap. “What EB-5 has allowed me to do is turn those ‘no’s’ into ‘yes.’”

Ironically, it’s the word “No” that someone has painted on the advertising poster for the Beckert’s Park project, right behind where Brunner is standing. It’s a two-letter reminder that some complain EB-5 projects are gentrifying neighborhoods to make them unaffordable for long-time working-class residents. A Washington Post article touting Brunner’s role in NoMa’s makeover also quoted a 67-year-old long-time resident as saying most of her fellow black neighbors have moved away and that “I’m all for change, but it’s so evident what they do for white folks.”

When someone presses Brunner on gentrification, she says she counters with, “What’s your plan for bringing jobs to the neighborhood?” The Safeway, she argues, will provide dozens of jobs that don’t require a college diploma, just like many of the openings at luxury hotels she’s helped finance.

Brunner’s backstory, and her skill in forcefully defending the EB-5 program, made her a natural choice to become spokesperson for the EB-5 Investment Council at what is a particularly fraught time. Since 2015, Congress has passed only short-term continuations of the program—while its detractors have grown louder.

Some critics compare EB-5’s green card benefit for the wealthy unfavorably to the sharp decline in refugees that, under the Trump administration, America has been taking in from places like war-torn Syria. That’s on top of several publicized cases of investor fraud and national scrutiny after relatives of Trump’s son-in-law and senior aide, Jared Kushner, traveled to China to market EB-5 investments in a Kushner project in Jersey City.

Brunner, who’s defended the program on cable news and in testimony before Congress, has ruffled a few feathers among her colleagues by saying she welcomes more regulation. But, she insists, detractors aren’t giving EB-5 enough credit for its urban renewal success. When Brunner pitches investors in Asia and elsewhere, she’s competing against citizenship programs in other developed nations—“and we’re the only program in the world that has job creation as a requirement. We’re requiring direct economic benefit.”

“She’s one of the few people I’ve seen really connect the dots” on rebuilding urban neighborhoods and how the EB-5 program can make that happen, says Brunner’s longtime friend John Hill, who tried and failed to hire Brunner when she first moved to D.C. and is now finishing a stint as Detroit’s chief financial officer. He adds that focusing on the job creation side of the visa program instead of the immigration issues “gives her that edge.”

At the EB5 Capital offices on a leafy highway near the Potomac in Bethesda, Md., wall clocks show the time not just in Washington but in Vancouver, Beijing, and Dubai. Inside a conference room, three men are waiting to meet Brunner: Indian citizens who came to America by way of Dubai. A would-be investor is accompanied by his father-in-law, a past EB5 client who received his green card that very morning.

“That’s the first time I’ve met a guy with his green card,” Brunner enthuses. The ever-changing nature of the EB-5 program—most investors used to come from China, creating such a logjam that today prospects mostly hail from elsewhere—has Brunner and her staff traveling the globe. You might assume she has time for little else. Until, that is, you remember Brunner’s “pace.” The former Brown rugby captain recently bought a new judo uniform and intends to get back into it, though at the moment she’s concentrating on the New York Times 7 Minute Workout and SoulCycle. In addition to her work with the EB-5 Investment Council and the expected array of business groups, Brunner teamed up with the Stonewall Community Foundation to support STEM-focused scholarships for LGBTQ youth. She’s a founding member of the Silicon Valley Blockchain Society, seeking projects with social impact, while financing independent movies and launching a project with the too-perfect name of The Angel Fund, to aid other women entrepreneurs. She’s working on raising her visibility as a thought leader, and attended the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, for the first time in January.

“I have to impact the most people in a positive way—that’s my true north,” Brunner says, pausing for a short break in a jazzy coffee bar near D.C.’s Union Station. Creating 30,000 jobs through EB5 Capital simply “sounds like a start to me.”

Will Bunch ’81 is national opinion columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News and author of several books including Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy.