Lessons from 1918

An expert on last century’s influenza pandemic shares what history could have told us about COVID-19... if we’d been willing to listen.

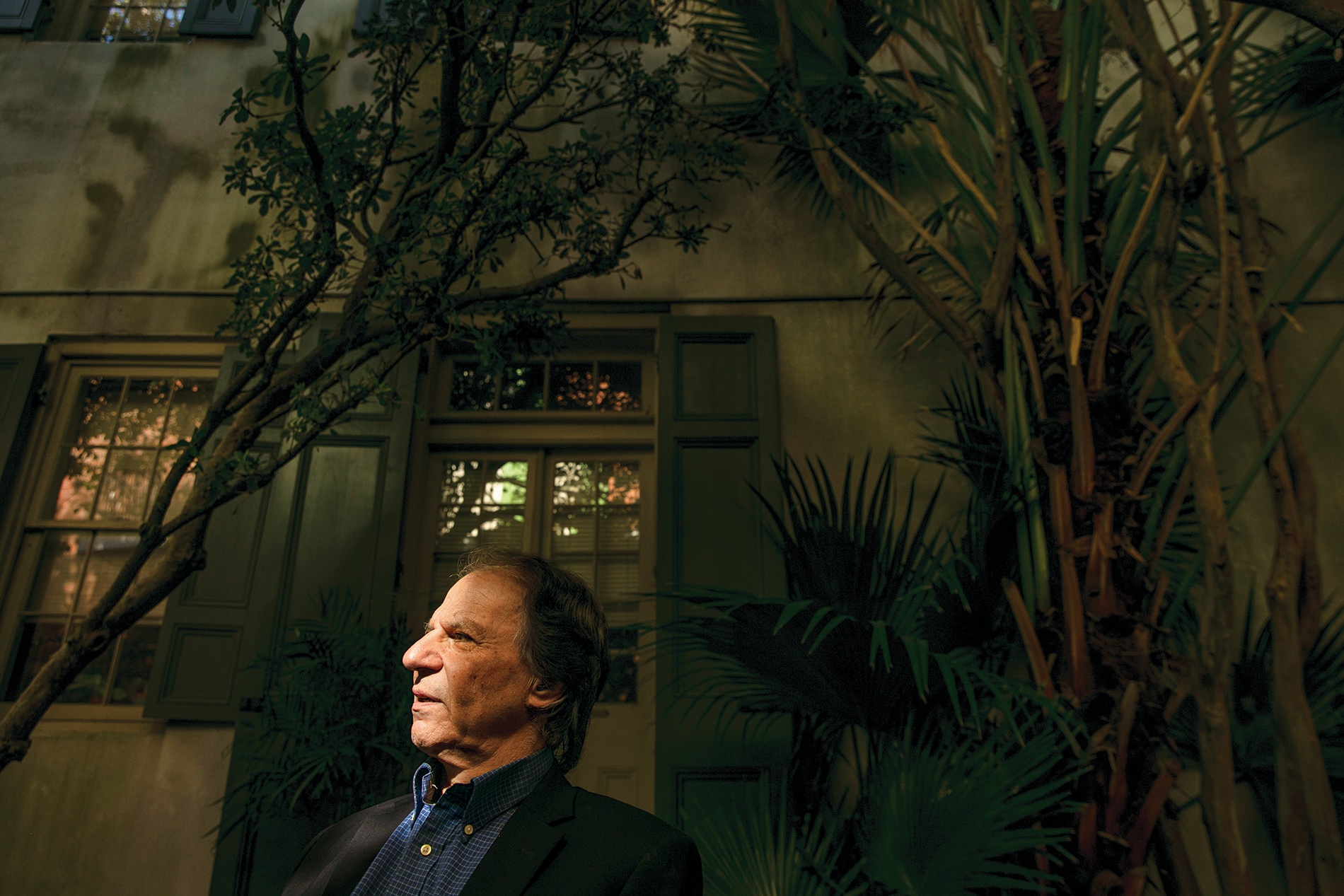

John M. Barry ’68 is the author of the 2005 best-seller The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, about the 1918 pandemic that killed between 50 million and 100 million people. He’s also a professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. He spoke recently with BAM contributing editor Stephanie Grace ’87 about the spread of the novel coronavirus and what lessons he draws from studying the events of 1918.

BAM: At what point in the corona-virus story did you start to draw comparisons in your mind to 1918?

Barry: I guess the first time I heard of this virus, I thought we were in for it. So that would be some time in early to mid-January, long before they closed down Wuhan.

What was it that got your attention?

I understand how a virus can move and how difficult it is to contain. From the beginning, I think the Chinese scientists have been very transparent. They got the genome up very quickly, which saved an enormous amount of time in terms of developing drugs and a vaccine, and the Chinese scientists were saying early on that they believed asymptomatic people could transmit. And when I heard that….

Could the outbreak have been contained in Wuhan using all best practices?

The Chinese have demonstrated an incredible capability of containment, which we do not have in the West. And had they been honest with themselves at the very, very beginning and recognized the seriousness with which they should have acted—any virologist would have told them immediately that this was a huge worldwide threat—then they could have applied the same measures and the world would have been a much better place. They would have had a chance of containing it. Once it escaped China there was no chance.

Why do you think it could have been contained in China but not the West?

Well, for one, the domestic surveillance technology the Chinese have, we don’t have, or we may have the capability without ever employing it. The Chinese employ it routinely. They have computer systems and algorithms and so forth. My understanding is that they could tell where everybody was, who was in the subway car with someone who turned out to be infected on any particular date, and go back. I mean very, very efficient contact tracing. So there aren’t too many places that have that.

However, other Asian countries that are free societies seem to have had very good success, infinitely more than the United States, in fighting this virus. I’m not an anthropologist, so instead of getting into a cultural analysis, let’s just say what is. Number One, the governments approached this with the seriousness it deserved, from the beginning. And Number Two, the public cooperated. This was true in Hong Kong, it was true in Singapore, it was true in South Korea, it was true in Japan. In the United States, the CDC and NIH and every public health officer with a brain took it very, very seriously by mid-January at the latest. But obviously you have a White House that did not, backed up by a sizable chunk of the media that attacked anybody who said this was a real threat. The results are twofold: We’re going to have a serious problem in convincing more or less everyone to comply with every element of what’s involved. And while we have slowed the doubling rate significantly, we have failed to achieve what we hoped for in terms of turning the curve downward.

How much of the problem is the White House and right-wing media ecosystem, and how much is what we’ve done to the federal government—the disinvestment, the anti-government philosophy that’s been around for a while now?

Well, messaging is an important part of what goes on with public health. Advisories are the most important part, whether you have a government that does everything or a government that does nothing. The widespread public support of compliance—you can only get that with a consistent, honest message.

Anybody involved in preparedness knows that we had a shortage of ventilators, a shortage of all sorts of supplies, but there’s been a disinvestment in public health in almost every state in the country, whether Democrat- or Republican-led. Most of the handling of something like this occurs at the state level.

I remember the H1N1 outbreak in 2009, which turned out thankfully to be a very mild pandemic. We didn’t know that when it started and people were gearing up, and I remember specifically that in one of the best-prepared cities in the country in terms of public health, the head of the department said she had to lay off 20 percent of her department days after the pandemic ended—even though they’d just been proven to be effective. This was a funding cut that was coming. They managed to just delay it for the pandemic, so after these people worked 18 to 20 hours a day for months, they lost their jobs.

Is there anything that strikes you as really different, comparing the current situation to this stage of the 1918 pandemic?

It’s a reasonably close parallel. There are of course differences. One is the target demographic of the virus in 1918. The peak age for death was 28, and probably two-thirds of the people who died were 18 to 50. Over 99 percent of the excess mortality in 1918 was people under 65 years old. So obviously, the elderly in their youth had been exposed to a very similar virus which gave them immune protection. It happened to have been so mild that it didn’t register in medical history, and yet it was similar enough that they had protection. This time around it’s exactly the opposite.

Another difference is this virus moves through communities quite a bit more slowly than influenza. The incubation period for influenza is one to four days, usually two days or less. This virus, the mean is five to six days—it ranges from two to 14—plus the incubation period is more than twice as long and people are sicker for much longer. The silver lining for all this is that it gives you an opportunity to do contact tracing.

How about how global we are now, how we travel around the world easily and quickly compared to then?

Well, people seem to think you need an airplane for a pandemic, but obviously in 1918 it moved pretty quickly without airplanes. One of the questions is why the rest of the world seemed to pay no attention even after Wuhan exploded in January, and my answer is: good question. Certainly airplanes spread things much faster, but we still had several months to get ready and we weren’t.

How would you compare the level of disruption?

The disruption in the larger sense is much bigger today. Speaking about airplanes, that’s a huge chunk of the American economy. In 1918, you didn’t really have to worry about supply chains the way you do today, because so many things were locally sourced or regionally sourced. I mean, so many things now, including masks and surgical gloves and hypodermic needles, they’re all made in China.

How much economic dislocation was there in 1918?

It’s difficult to say. Practically every industry in the country, certainly every manufacturer, was geared toward the war. Whether they were making uniforms, guns, ships, even railroad cars.

I know that there was a tremendous amount of absenteeism. If you were working in a coal mine or any mine, you were going to have a very difficult time if you had influenza. Shipbuilding, you got 40 to 60 percent absenteeism, so that was going to affect your production. In those days there was no sick leave. So clearly production was cut dramatically, but I don’t have any numbers on it, and it recovered very rapidly.

So what are the major lessons of 1918?

Well, the number one lesson is, tell the truth. That was incorporated in the federal pandemic plans, and it was incorporated into the plan for every one of the 50 states and however many territories there are. But you have to have someone who’s going to tell the truth. Someone has to stand up there at the top and decide to do it for it to be effective.

Is that what the government did in 1918?

No, they lied outright, and the result is more people died than would have otherwise. The motivation was because they were focused entirely on winning the war and didn’t want to say anything that might be interpreted as negative. That affected what they said about influenza.

Is there anything that makes you optimistic instead of pessimistic about where we’re headed now?

Well, we have intervened earlier and more aggressively than was the case in 1918, although not as early as we could have. So the question is, what kind of support for these measures from governors and what kind of sustained compliance from the public are we going to get? We still have a chance of mitigating the damage and keeping people alive who would otherwise die. That’s still in our power. Yes, we have to open the economy, but we need to do it carefully.

The other thing is that we have had very good international cooperation in the scientific community. People are sharing information and not worrying about credit. We have a very good chance of developing effective antivirals and a vaccine.

When this crisis is over, what do you hope the federal government will have learned?

It’s not a question of what the government learned, it’s a question of what whoever is president learned. And that is that preparation is good, investment is good, transparency is good.

When my book came out and bird flu resurfaced at the same time, the Bush administration took it very seriously and put a lot of money into it, but that focus ebbed over time. With H1N1 in 2009 when Obama was in office, I was speaking quite regularly with people in the White House. They were pretty focused and it took a while to develop the vaccine, but that was nonetheless very, very rapid.

[But] there wasn’t a desire, largely but not entirely by Republicans, in Congress. They don’t like to invest in government. Public health is part of government. You

buy ventilators and they sit around and people ask, “Why are we spending all this money on ventilators and N95 masks and so forth that just sit around? Shouldn’t we use that money on something else?”

A good question. Now we know the answer.