Performing Sin

Inside the world of anti-trafficking organizations, where former sex workers who attend Christian church services and weep in shame over their past behavior get reduced hours and higher wages.

The neon sign read Honey Money. “It’s happy hour, come have a drink!” called a young woman in the doorway. Elena Shih hesitated. It was 2008; this was her first trip into Bangkok’s red-light district conducting research as a volunteer for a U.S. anti-trafficking group. The organization’s goal was to save victims of sex slavery. Every Tuesday, volunteers hit the go-go bars.

Shih followed a volunteer named Ally inside to a vinyl booth in front of the stage. Above her, women in lingerie danced to Britney Spears’s “Toxic.” Each had a number taped to her body so audience members could call her down. Shih felt nervous and sweaty. At that hour, being at the empty bar was “definitely very awkward,” says Shih, laughing at the memory. “The only people there were white missionaries.” She asked Ally how to choose a dancer. “Trust the Holy Spirit to connect with anyone who compels you,” Ally said.

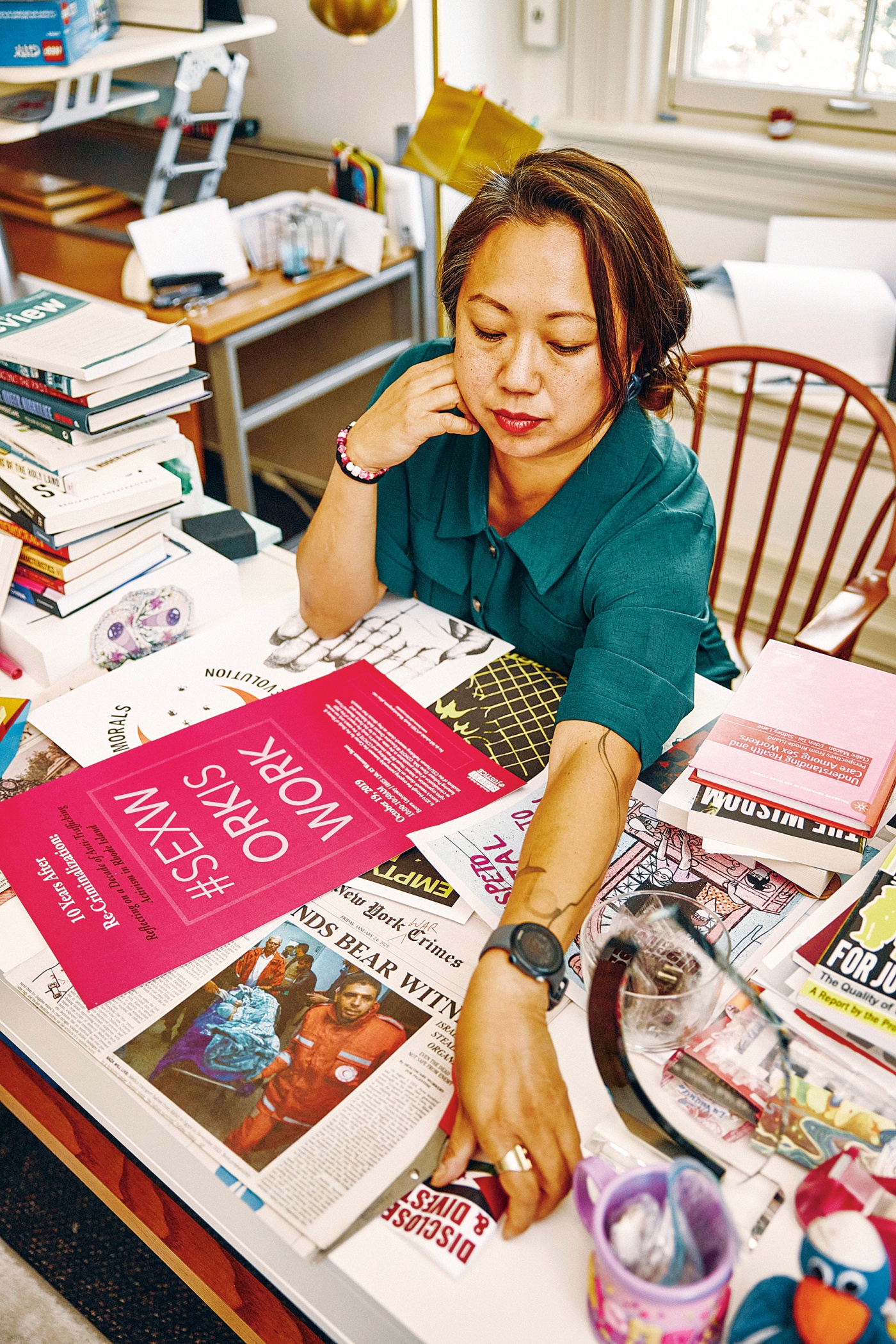

Shih, now associate professor of American and ethnic studies and associate director of academics for Brown’s Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, went on to spend years as a participant observer across Thailand and China. She focused especially closely on two U.S. anti-trafficking organizations working in Beijing and Bangkok. The result was one of the first ethnographies of East Asia’s international anti-trafficking sector, which Shih summarized in her award-winning 2023 book, Manufacturing Freedom: Sex Work, Anti-Trafficking Rehab, and the Racial Wages of Rescue.

Shih’s conclusions—biting critiques of the anti-trafficking industry—are twofold. First, many

anti-trafficking groups rarely interact with the types of abuse victims that they say they do. Second, the rehabilitation-style work programs they operate can cause as much harm as they do good.

Critical anti-trafficking studies is a nascent discipline; Shih is one of its original architects. She started her ethnography four years before the first academic anti-trafficking journal put out its first issue in 2012. “I’m considered an expert on trafficking, and it’s something that I feel quite ambivalent about because of how many harms anti-trafficking has espoused,” Shih says. Her goal now is to leverage her position to raise awareness of those harms.

Shih suspected that nothing more sinister than market forces tied the women at the center of this mission to commercial sex.

The wages of victimhood

Shih’s research was immersive. She spent three summers between 2008 and 2010 on the floor of a Beijing-based U.S. anti-trafficking rehab center that trained former sex workers in jewelry production, pinching strands of red rope between her thumb and index finger and trying to ignore the burning sensation in her fingertips. For weeks, Shih struggled to seal the fraying ends of the bracelets they were making. First, melt the rope with a candle; next, roll it gingerly into shape. Shih could feel blisters forming by the fifth attempt. “Why can’t I just use a glove?” she asked, to the amusement of the other workers at her table.

Many anti-trafficking organizations claim to rescue victims of sex slavery. It’s a narrative that evokes images of kidnapped girls and battered women, pimps and organized crime. Shih observed that the reality of anti-trafficking work was much more banal. When recruiting jewelry workers, the organizations she worked for didn’t ask women if they had been trafficked—that is, forced, defrauded, or coerced into sex work. They simply ventured into red-light districts and recruited any sex workers they could find.

Shih suspected that nothing more sinister than market forces tied the women at the center of this mission to commercial sex. So she asked jewelry workers at two different U.S. nonprofits how they felt about the trafficking label. Most women flat-out rejected the notion that they had been trafficking victims. They “insisted that no one had forced them into those situations” and that “they could have left whenever they wanted,” Shih writes. Many said they chose sex work because it was their only way to make enough money to remit to family members in the countryside. They switched to jewelry-making for similarly prosaic reasons: the anti-trafficking groups offered unique benefits like childcare.

Regardless of how workers self-identify, anti-trafficking groups make their money off the idea that they’re saving victims of violence. The American appetite for opportunities to help trafficking victims is voracious, within the jewelry market and beyond. There are victim-made wallets, coffee, and notecards; even “anti-trafficking reality tours” of supposed crime hotspots costing thousands of dollars, which the New York Times touted as “a vacation with a purpose” in 2017.

The liberation narrative is so essential to making jewelry profitable that women who leave

anti-trafficking organizations cannot get by selling jewelry alone. In 2012, Shih visited former workers who had left the anti-trafficking groups after getting married. Yin was living in the port city of Yiwu, where she still worked in the jewelry business. But survival required 18-hour days of labor for her husband, for no pay. She soon returned to her position with an anti-trafficking group for a more tolerable life. Jade had taken a job at a string factory after failing to make a profit selling jewelry. When Shih visited, she found Jade frustrated that she couldn’t afford to divorce her indolent husband. “It’s a shame,” she told Shih, “if I was still a ‘victim of trafficking,’ I bet I would be eligible for free legal aid.”

Jade understood exactly why she could not afford the services that the big U.S. nonprofits provided. “I know why we were able to ask for such high prices: they told Americans all these tragic stories about our lives and people felt bad for us,” she said. “I don’t think they needed to say it was horrible as human trafficking; they could have just said it the way it is: we have hard lives.”

Yin and Jade had nothing to sell as valuable as the idea that they were being saved. Ironically, that reality undermines anti-trafficking groups’ claims to offer valuable vocational training. “We spent a lot of years talking about vocational training, but I still fundamentally lack an education,” Yin told Shih. “The only kinds of jobs I can apply for are service sector jobs that pay very little.”

The morality of “femininity”

If the women working for anti-trafficking organizations aren’t really trafficked, and the skills they receive aren’t really useful, then what do anti-trafficking groups actually do? Shih found that the organizations’ primary goal was rehabilitation. The groups she worked with subscribed to the idea that sex work is immoral. Her bosses also believed that women would only do sex work if they didn’t know that it was wrong. Anti-trafficking organizations existed to educate sex workers and scaffold them onto more dignified paths. “The act of making beautiful jewelry restores femininity to where femininity has been lost,” one U.S. group’s employee told Shih.

Yin and Jade had nothing to sell as valuable as the idea that they were being saved.

Shih found that anti-trafficking employees viewed the jewelry workers as backward and confused. Interpersonally, they treated former sex workers with disrespect. Institutionally, the groups took numerous steps to transform jewelry workers’ personal, religious, and cultural values.

Workers were expected to prove that their values were changing by demonstrating shame and remorse for having done sex work. Shih recalls one night of “group counseling” when a staff member passed around a roll of toilet paper and told everyone in the room to tear off a piece. It was soon revealed that each worker would be obligated to answer as many personal questions as she held toilet paper squares. “What are you most ashamed of in your life? What is the most important thing that you have lost? Who has hurt you the most in your life?” the staff person demanded. Nobody was allowed to move on until they cried. Tears of remorse were so frequently required that workers coined a term for crying on cue: biaoshi zui, or “performing sin.”

Anti-trafficking groups did not blame only sex workers for their moral failings—the groups also faulted Thai and Chinese culture. Some told Shih that Buddhism was responsible for trafficking because it promoted gender inequality. On Shih’s first recruitment mission in Soi Cowboy, a famous street in Bangkok’s red-light district, her companion Ally pointed out a woman with a tattoo of a Buddhist Pali incantation. “It’s a symbol of demonic possession by satanic forces,” she said. “We like to engage girls with that tattoo because we find that those girls need us the most.” Shih’s characterization of the prevailing attitude: “Women working in Bangkok’s red-light districts are passive victims of bad culture and poor family values.”

Anti-trafficking groups encouraged conversion to Christianity. This solution is not surprising, given that the anti-trafficking sphere is dominated by Christian groups. “Human trafficking was not even ‘on the screen’ until the tireless work of evangelicals placed it there,” said Chuck Colson, a prominent evangelical. Shih observes that major nonprofits like the Nomi Network and International Justice Mission, which appear secular at first blush, can be traced to nonsecular roots and funding sources.

While one group’s staff told customers that jewelry workers were not required to attend religious services, they didn’t disclose that women who opted out of daily church time had to work for an extra hour instead. At another, workers’ promotions were directly tied to “their commitment to living the teachings of Jesus Christ.” Pious workers would be more docile and productive, managers reasoned.

Beyond religion, even basic cultural differences were construed as faults. One group’s employees often cited workers’ lack of aesthetic taste as a reason that they did not get to create their own jewelry designs. “We let them dabble in designing some of the jewelry one time, and we ended up with all these pieces that were this ugly combination of yellow and purple,” a staff member explained to a crowd touring the jewelry shop. Yellow and purple is a patriotic color combination in Thailand, utilized by Thai Airways and the Siam Commercial Bank.

Shih was a regular witness to the denigrating way that anti-trafficking staff treated jewelry workers. One Saturday, when Yin still worked at one group, she took Shih to visit her boyfriend at a local bakery. Before they left, Shih stopped by the common room to ask if anyone else wanted to come. No one did, which made the supervising staff member angry.

“You have this volunteer here—from America!—who wants to take you out to see things in the world and learn new things… and all you want to do is sit inside and play on your phones,” she said. Then she turned to Shih. “It really takes a lot to move people beyond brokenness,” she said in English.

Workers abided this treatment to access benefits like healthcare, childcare, and weekends off. Shih characterizes this as a difficult calculation which comes out in favor of short-term economic benefits. On the level of the individual worker, anti-trafficking groups provide marginally better employment opportunities at the price of respect and autonomy. But on a broader scale, Shih says the rehabilitative approach to anti-trafficking work has serious consequences.

“Rehab allows moral notions of redemption to do the work of justice.”

Redemption vs. justice

“Rehab is bad for workers,” Shih argues, because “it allows moral notions of redemption to do the work of justice.” The jewelry workers that Shih met shared one primary complaint: economic oppression. They craved major political and economic reforms that would offer them more job opportunities, and stood in solidarity with labor movements spearheaded by other low-wage workers.

As long as structural change eluded them, low-wage workers in a variety of industries made the best of the system they had by organizing themselves. Sex-worker rights groups like Thailand’s Empower Foundation, which Shih has worked with, advocate for fair labor practices and protested the criminalization of sex work, which can strip poor women of one of the few opportunities they have to make a comfortable salary.

None of the tactics low-wage women workers used to uplift themselves had anything to do with jewelry-making. Workers just didn’t see jewelry jobs as a real solution to the problem at hand.

Yet Western customers only heard the story that anti-trafficking groups promoted: that they were using the income generated from jewelry sales to give “trafficking victims” what they needed. The narrative of rescue pulled resources toward people who claimed to know what poor women needed—and in doing so, away from those women themselves. Americans looking to give charitably are more likely to buy “slave-free jewelry” than to donate to Thai sex-worker mutual aid funds, especially if the first option seems as useful as the second.

Yet low-wage female workers can’t powerfully campaign for rights or systematic economic change without substantial attention and funding. Shih argues that anti-trafficking organizations co-opt resources intended to help poor Asian women. Since that co-option undermines labor organizing, it re-entrenches existing economic oppression.

Shih’s ethnography is motivated by “a fundamental concern with how and why counter-

hegemonic movements may reproduce the same hegemonic power structures that they aim to combat.” Publicly documenting how anti-trafficking groups operate is part of empowering the women that they serve.

Personally, Shih thinks we could do away with most anti-trafficking organizations—and certainly all that resemble those she studied (the group’s names are anonymized in Shih’s writings, as required by the ethics committee that oversees research in this field). “Singling out only former sex workers and victims of sex trafficking as those deserving of decent work misses the opportunity to create systemic change,” she writes. As long as the anti-trafficking sector persists, however, she challenges groups within it to start asking their employees what they actually want, instead of dictating what is best for them.

Shih’s commitment to uplifting marginalized women from the ground up extends from her research in Asia to local politics. For over a decade, she has worked with local sex worker rights groups—like Red Canary Song in New York City and Ocean State Advocacy in Providence—to help sex workers conduct their own community-based research. She is an outspoken advocate for Asian spa workers, who are criminalized for sex work at much higher rates than their white counterparts throughout the Northeast. In 2022, she partnered with the ACLU of New York to write a bill that would decriminalize unlicensed massage work, which was introduced on both the NY House and Senate floors.

Shih says she tries to take advantage of her position as a trafficking expert to raise awareness about the serious harms of what many people consider mundane forms of labor abuse. Much of the work is “asking people who are maybe only interested in trafficking because it’s fashionable to come along for the ride and look at how we understand root causes.”

Shih’s 2023 book—which has received awards from the American Sociological Association, the Society for the Study of Social Problems, the International Conference on Abuse, and the Working Class Studies Association—is not a bombshell. Sociologists began studying the harms of anti-trafficking nonprofits at the beginning of the past decade.

Yet it is a monument. It’s the product of fifteen years of labor—“a prodigious amount of fieldwork,” writes a reviewer in the American Journal of Sociology—and it stands alone in the field in terms of the depth of its empirical research. Scholars emphasize that Shih’s elegant argumentation and overwhelming evidence make the work an essential read not only for academics, but for “human rights and labor activists, feminists, policymakers, and the public in general.”

For her part, Shih wants the American consumer to know that the “slave-free” jewelry and other goods they may see are often not only sold at a premium, but are based on a fantasy.

She applauds those who wish to support low-wage workers. But the freedom bracelet on offer at the craft fair might be a tool not of liberation but of a different kind of oppression.

Meg Talikoff ’25, a psych concentrator planning to go into couple and family therapy, was an editor of BAM’s April student-edited issue.