“Old Brick” at 250

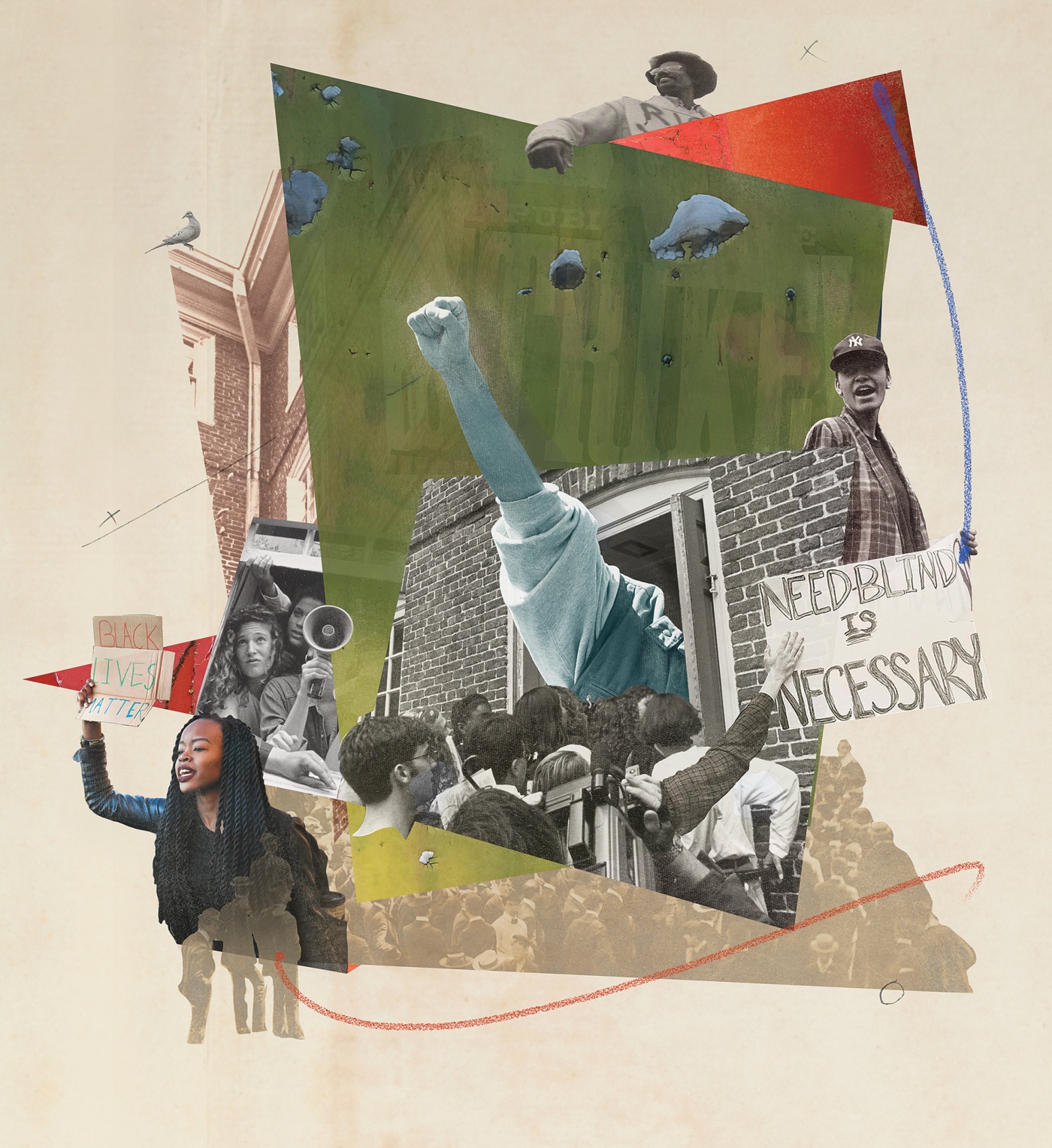

University Hall is no stranger to pandemics or cancelled commencements—like the one in 1776. Since 1770, Brown’s first “College Edifice” on College Hill has seen the horrors of slavery, a visit from a Founding Father, dormitory hijinks, U.S. soldiers, and student protests….lots of protests. A brief history.

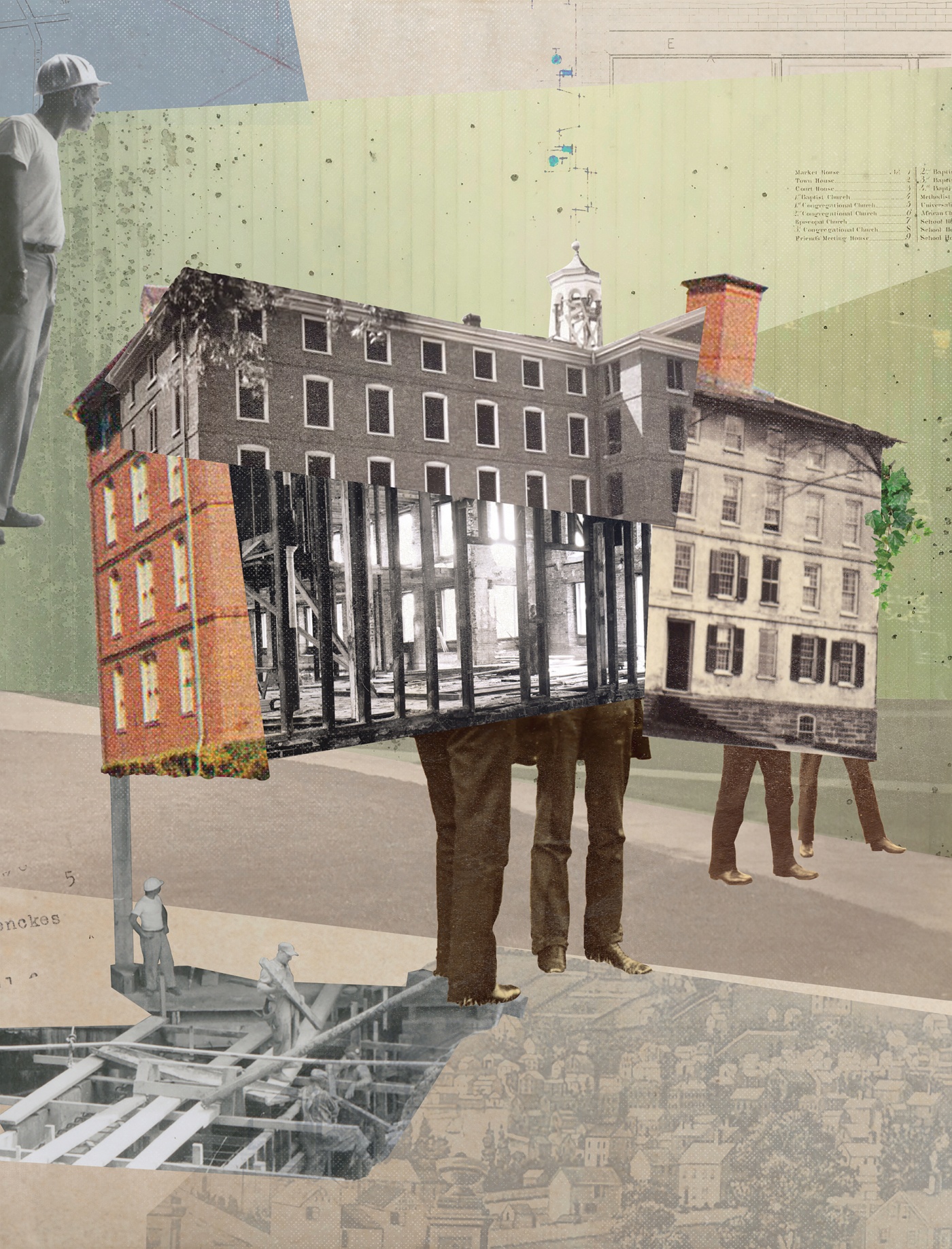

At the time—the late 1700s—a lot of people thought putting a big university building in the then sparsely populated neighborhood at the top of what’s now known as College Hill was a really stupid idea. For one thing, it was a huge building and the school had only 21 students. Today’s 10,000-plus enrolled degree-seekers were unfathomable. The Boston Gazette ridiculed it as “a College near as large as Babel; sufficient to contain ten Times the number of students that ever have, or ever will oblige the Tutors of that popular University.”

Moreover, the location was just a pain in the neck to get to, trudging up the steep hill from Benefit Street and the Providence River waterfront. “Complaints were registered about the ‘inaccessible mountain’ that had been chosen,” wrote Ted Widmer, a former Brown history professor and a former director and librarian of the John Carter Brown Library in his 2015 book Brown: The History of an Idea.

But the hilltop location in Providence won, beating out Newport as a place for Rhode Island College, as it was then known, to move to.

The school had been located in Warren, R.I.—today 20 minutes from Providence by car—since its founding in 1764. On February 9, 1770, trustees voted to move it to Providence, and on March 26 they settled on East Side land owned by John Brown, a slave trader, bank president, and politician, instead of another proposed location in downtown Providence. Rev. Morgan Edwards, a prime mover behind the school’s founding, gushed, “Surely this spot was made for the Muses.’”

Work proceeded quickly. On March 27, 1770, just one day after the decision to build on the East Side, Solomon Drowne of the Class of 1773 wrote in his diary: “This day John Wiley and 7 other persons begun to Digg the College Seller beginning to Digg at three o’clock in the afternoon and Dugg till twelve minuits after 6 when they had Dugg a hoole 30 feet Long & about 6 feet wide and 2 feet Deepe on an average.”

The identity of the architect of the building has never been conclusively established, with several people suggested, including Joseph Brown, a brother of John Brown who designed the John Brown House and the First Baptist Meetinghouse.

There was, though, a clear model for the new building: Princeton’s Nassau Hall, built in 1756. There was a strong Princeton connection to the then-named Rhode Island College—most prominently first president James Manning, who was from Princeton’s class of 1762.

“How do we reconcile those elements of our past that are gracious and honorable with those that provoke grief and horror?”

—Brown’s 2006 Slavery and Justice Report

When John Brown laid the cornerstone at the southwest corner of the building on May 14, it was reported he treated the audience to punch, perhaps spiked with rum. Rum, then produced thanks to the Triangle Trade—in the Colonial era, Newport, R.I., was the rum capital of the world—would become a motif in the construction that followed, used as an incentive to get workers to move quickly. There were rum “bonuses” when each stage of construction was completed, ending with “raising the roof.” By June 28, the first floor was laid; August 2, the second floor; and on October 13, the roof. The total cost was less than $10,000. Still, there was not money to complete the third and fourth floor—which would not be finished until 1788.

Considerable funds had been raised for the building, then known as the College Edifice, and the record shows that some donors paid their pledges by forcing enslaved people to work on it. A Nicholas Brown & Co. ledger with clear references to enslaved people was available and even publicly displayed in the building. Yet that aspect of the building’s history “was easy to overlook,” wrote former University curator Robert Emlen in Rhode Island History, “as an amnesia about African slavery in New England settled so thoroughly.”

In 2003 the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice appointed by President Ruth Simmons found, alongside the University’s other ties to slavery, evidence of four enslaved men who had labored on the building. Only one of them was named: Pero, who was owned by Henry Paget, a Providence merchant. The three others were known by their owners’ names. The committee called it “a history that has long hidden in plain sight” and its 2006 report wondered, “How do we reconcile those elements of our past that are gracious and honorable with those that provoke grief and horror?” The report turned to a 1914 sermon by former Brown President Rev. William Faunce: “It is not only ivy that clings to ancient walls—it is memories, echoes, inspirations. The very stones cry out a summons....” He continued: “Have we entered so new a world that we have no further connection with the generation in which these colleges were born? To think so would be to show ourselves without the sense of either historic continuity or moral obligation.” Today, UHall hosts a standing exhibit that describes the building’s slavery era past.

Another history long hidden in plain sight is the University’s location, as with the rest of the U.S., on Indigenous homelands. A Land Acknowledgement Working Group will develop recommendations about “how best to acknowledge the land connected to local Indigenous Peoples and the University, and our shared history related to these spaces,” wrote President Christina H. Paxson in a March announcement. “I am glad to see the University moving in the direction of a slow and engaged process regarding the best course of action,” said one of the working group’s cochairs, D. Rae Gould, associate director of Brown’s Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative and a member of the Nipmuc Tribe of Massachusetts. Another recent development: a $4.9 million Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant will enable collaboration between Brown, Williams College, and Mystic Seaport Museum scholars to study the relationship between European colonization, dispossession of Native American land, and racial slavery. -:

Up and running.

The College Edifice went into use in 1771, when the school’s enrollment was about 20. Then, almost immediately, came a major interruption. As war with England approached in 1776, British and Hessian troops landed at Newport. Colonial militia gathered in Providence to shore up Patriot defenses and the College Edifice was taken over to house soldiers. “This town has been a garrison,” President James Manning wrote to a friend. Manning kept teaching some students at his president’s house (built at the same time as the College Edifice near the current location of Carrie Tower), but there were no commencements after 1776 until 1782.

After American troops decamped from the College Edifice in 1780, it was taken over by

the French as a hospital for wounded soldiers. By the time the French left in 1782, the building was in terrible condition, and the school spent the next 18 years trying to get Congress to pay for repairs. In 1800 the U.S. Congress and President John Adams approved $2,279.13 for repairs, a far cry from the $7,667 requested. The college did the renovations it could afford.

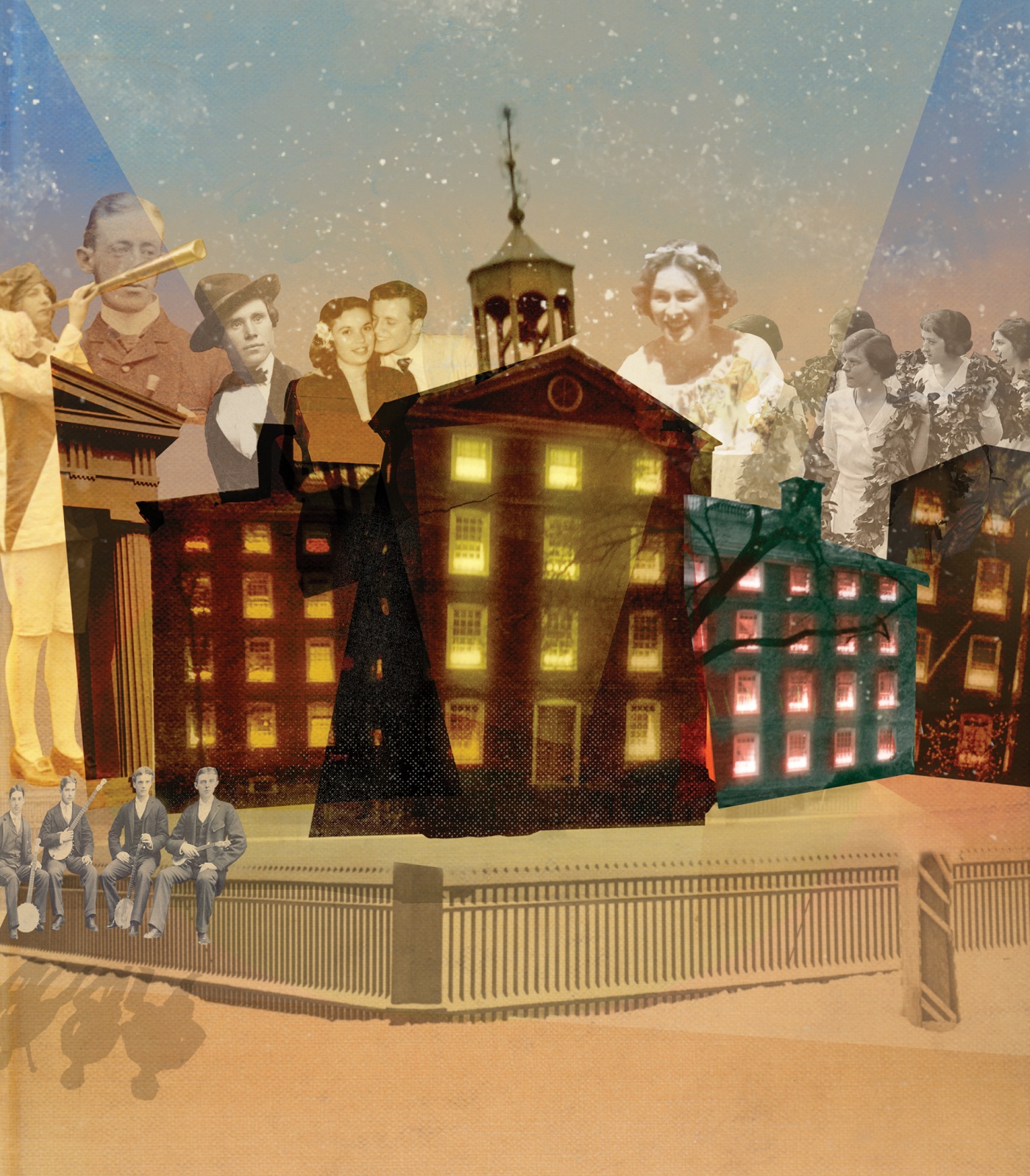

Long halls the length of the building opened up opportunities for mischief, such as bowling tournaments—using cannon balls. “The upper story was called Pandemonium and not infrequently deserved the name.”

—Edward Cutler, class of 1857

Even while the school was battling the Congress for money, a historic encounter with the U.S. government happened in 1790. When Rhode Island became the last state to ratify the Constitution, President Washington came to visit. On August 18, he arrived in Providence by boat from Newport, an arduous seven-hour trip. Washington, accompanied by Thomas Jefferson, senators, and other officials, was greeted by crowds and cannon salutes. That evening he was told that the students of the College had prepared a tribute to him. From the tavern on Benefit Street where he had had dinner, he walked up the dark hill in gloomy rain to see the College Edifice lit up with tallow candles in each of its windows, starting the tradition of illuminations that continues to the present day (see sidebar on page 26). In 1932 the University celebrated the bicentennial of Washington’s birth by unveiling a plaque on University Hall commemorating his visit.

Since it was built in the days before photography, some of the first images of the College Edifice came from the students of Mary Balch’s school on George Street, where girls were taught skills including needlepoint. A number of girls chose the College Edifice for their needlepoint samplers, and several remain in Brown’s John Hay Library collection, such as Abigail Adams Hobart’s “Wrought in the 10th Year of Her Age June 11 1802.” Other samplers done at Miss Balch’s school are in the collections of museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

As the young college’s only building, the College Edifice held everything—offices, classrooms, library, and dorm. The building got the nickname of “Old Brick” in early years, and rent for a dorm room was $5 a year. Liquor was banned from student rooms, and while there was no direct mention of visits from members of the opposite sex, a ban was set down in 1775 on “private entertainment” in rooms. Long halls that went the length of the building opened up opportunities for mischief, such as bowling tournaments—using cannon balls. Edward Cutler, class of 1857, wrote: “The upper story was called Pandemonium and not infrequently deserved the name.”

Over the years, many students who lived in University Hall went on to high-profile careers, such as three U.S. secretaries of state (William Marcy, class of 1808; Richard Olney, class of 1856; John Hay, class of 1858), the longest serving president of the University of Michigan (James Angell, class of 1849), and a noted educational reformer (Horace Mann, class of 1819).

In 1804, the name of the school changed to Brown University in recognition of a $5,000 gift from Nicholas Brown, a prominent Providence businessman and alumnus, class of 1786. A second building, Hope College, was opened in 1822, and soon afterward University Hall was given its current name.

“Its defaced walls, the gaping flooring of its hall-ways, and the unmistakable odor of decay pervading the building, made parents who came to select rooms for their sons turn from the premises with ill-concealed disgust.”

—President Ezekiel Robinson, 1870s

The building again became a barracks in the early 1840s, as soldiers poured into Providence as part of the Dorr Rebellion, an attempt by middle-class residents led by Thomas Wilson Dorr to bring broader democracy to Rhode Island. Thousands of soldiers amassed in Providence so quickly that housing couldn’t be found and Brown agreed to put them up in University Hall. The crisis lasted only a few days, but Walter Bronson wrote in his 1914 history of Brown: “The veteran University Hall, dreaming of the past through all its old bricks and timbers, might well have fancied that the Revolutionary days of its youth had come again.”

The middle of the 19th century was not kind to University Hall. In 1834, the new Manning Hall was opened with a covering of cement, and the idea was hatched to make University Hall’s bricks match it. The cement was applied and stayed until 1905, though it had become shabby long before then. In the 1870s, President Ezekiel Robinson wrote that “its defaced walls, the gaping flooring of its hall-ways, and the unmistakable odor of decay pervading the building, made parents who came to select rooms for their sons turn from the premises with ill-concealed disgust.” The Brunonian, Brown’s first student publication, called it “a relic of the past.” Despite calls to tear it down, Robinson raised $50,000 for a renovation of the interior that quieted critics. He had the exterior stucco painted with an olive tint.

As America joined World War I, University Hall again was put into service as a Navy barracks for a few months in 1918. In the 1920s, the dorm capacity of University Hall was reduced as demand for faculty and department space grew.

The big renovation.

The arrival of Henry Wriston as Brown’s 11th president in 1937 brought big changes. Wriston was unusual for a Brown president in many ways. Born in Laramie, Wyoming, he was the first president of the University who was not a Baptist minister, and also the first president in nearly 100 years who was not an alumnus.

The new president was determined to improve the school in image and substance. He saw in University Hall a chance to burnish the brand of Brown with the link to colonial architecture and its connections to long-established schools like Harvard, Yale, and William & Mary. For Wriston, tying University Hall back to its colonial roots was essential to showing the world the age, wisdom, and value of Brown. There were only 10 older structures of colonial architecture remaining at universities around the United States, so it was a way to be distinctive. He went to a wellspring of colonial style, hiring the Boston architect firm Perry Shaw and Hepburn, which had restored Colonial Williamsburg. It would be the start of a colonial architecture building-and-renovation trend on campus.

At one point all the windows were taken out and the building was a brick shell. A lengthy search had been mounted to find the building’s original plans, but they were never located. So the architects and Wriston and his building committee worked from other documentation of how the building looked, as well as the examples of several landmarks of colonial architecture, such as the John Brown House.

“This is a moment of anxiety over liberty and its blessings. Democracy is on trial for its life both here and abroad. The history of this building, what has been said and done here in war and peace, in public and in private, reminds us that it has ever been so.”

—President Henry Wriston, 1940

By the time the project was finished, the building had undergone a gut renovation, the last dorm residents and academic and other departments had moved out, and the modern University Hall was a centralized administration building, including the current Corporation Room where Brown’s trustees meet. Wriston’s dozens of typed memos show his determination that the building be meticulously created in the image of 1770 while also ready for the current day.

In May 1940, with World War II underway, more than 2,000 people assembled on the Green as Wriston and others spoke from a platform in front of University Hall in celebration of the re-opening of the building. Wriston used it as an opportunity to talk about the times and the building:

“This is a moment of anxiety over liberty and its blessings. Democracy is on trial for its life both here and abroad. The history of this building, what has been said and done here in war and peace, in public and in private, reminds us that it has ever been so.”

In 1963, University Hall was designated a national landmark with an unusual twist. The U.S. Department of Interior was emphasizing ties to education in its landmarking, and Brown had the right connection for that: Horace Mann, who lived and studied in University Hall. Mann had become the best known educational reformer of his age, creating the nation’s first state board of education in Massachusetts and a system of public schools in Massachusetts that was a model for public education across the country.

After landmark status was granted, a ceremony was held May 5, 1963, on the Green, complete with people on horseback in Revolutionary Era garb.

In a remembrance of that day from someone who missed the ceremony, David Cameron ’31 said he’d unfortunately arrived from out of town too late. He had lived in University Hall as a senior and it had been a memorable experience. He convinced someone to let him in the building and up to his old room, which had become the fourth-floor hideaway office of President Barnaby Keeney. In the column he wrote for the Providence Evening Bulletin, Cameron said he left the building “feeling that it and my old room had come up in the world.”

Elevated perspective.

Today, University Hall includes the offices of most top Brown administrators, including the President and Provost—when they’re not working remotely. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the undergraduate interaction was on the second floor with the offices of the Dean of the College. Admissions tour guides stand close to the building as they talk about the University’s history, and sometimes guides of the Providence Ghost Tour lead guests there by lantern light at night, telling their version of history.

“The location [of University Hall] was unlike any previously chosen by an American college. Not one of the colleges that preceded Brown rested on an elevation to match it,” wrote Widmer in his 2015 history. “Ever since ancient Athens, hilltops have been places where humans beings dare to think like gods…More than most universities, Brown truly sits atop a hill, able to contemplate the splendors as well as the imperfections of the world, blessed with a home that furnishes each on a daily basis.”

Noel Rubinton ’77 is the editor of IMPACT magazine.