Ellen Hills ’42 has given a lot of thought to her death, not only to her will or to the various diseases that might kill her, but to exactly how she wants to be buried. “Just wrap me up in the quilt my grandmother sewed for me and put me in the ground,” the 86-year-old central Maine resident says. “I want my body to become the soil.”

This desire led Hills and her husband, James, on a four-year quest to create a “green” cemetery on a parcel of land that’s been in her family since the late 1800s. Under the rules of the new cemetery, bodies must be buried without any embalming fluids and in biodegradable caskets. Corpses buried there will eventually decompose and become part of the earth.

According to the Centre for Natural Burial’s Web site, six natural, environmentally friendly cemeteries have been established in the United States since the first one was created in 1998. Typically, bodies are refrigerated or kept on dry ice to ensure that they don’t start to decompose before the public viewing. Caskets are made from pine or biodegradable cardboard. The only thing that marks each grave is a flat, small stone natural to the area.

Hills’s proposed graveyard lies on a fourteen-acre plot along the Penobscot River in South Orrington, Maine, just south of Bangor. As a teenager, she camped there every summer in a one-room cabin that her father, Charles Walter Annable, built in 1936. He named the parcel “Rainbow’s End” for a rainbow that suddenly appeared arched across the river in the wake of a violent thunderstorm. In a letter Annable wrote to his daughter in 1938, he said the land was “practically the same year after year” even though “life with its complex experiences moves on at such a pace that it destroys our belief in an unchanging reality.” This small swath of forest and sloping plains, he added, offered the “illusion—or is it illusion?—of security and peace.”

Hills says it’s this sentiment that made her want to create a green cemetery. She says the cemetery will ensure that the land her family cherished for over a hundred years “will always remain exactly as it currently is.”

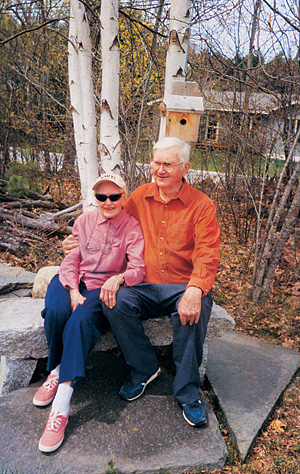

In October, Hills, a retired nurse and schoolteacher, started a nonprofit corporation to manage the land after her death. Her goal is to sell about 100 five-by-ten-foot plots at $750 apiece. According to Hills, the money will be enough to maintain the land in perpetuity.

As of late November, only one person besides Hills had signed up to be buried in the cemetery: her husband James, 85. Then a woman called. She wanted to bury her stillborn baby in the cemetery. Hills immediately assented. “It’s been a lot of work,” she says. “But absolutely it’s been worth it.”