Stage sets adorned with strange fragments of Rube Goldberg machines, divided up with striped lengths of string, labeled in English and Hebrew. Soundscapes that marry ominous rumbling with endlessly looping bits of music. Actors in bizarre costumes randomly dancing, throwing things, waving things—with slo-mo, dreamlike precision. Deadpan, cryptic lines such as: “Truth revealed, believe it or not, takes the unfortunate shape of everything that isn’t true.” And titles like My Head Was a Sledgehammer, King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe! and Rhoda in Potatoland.

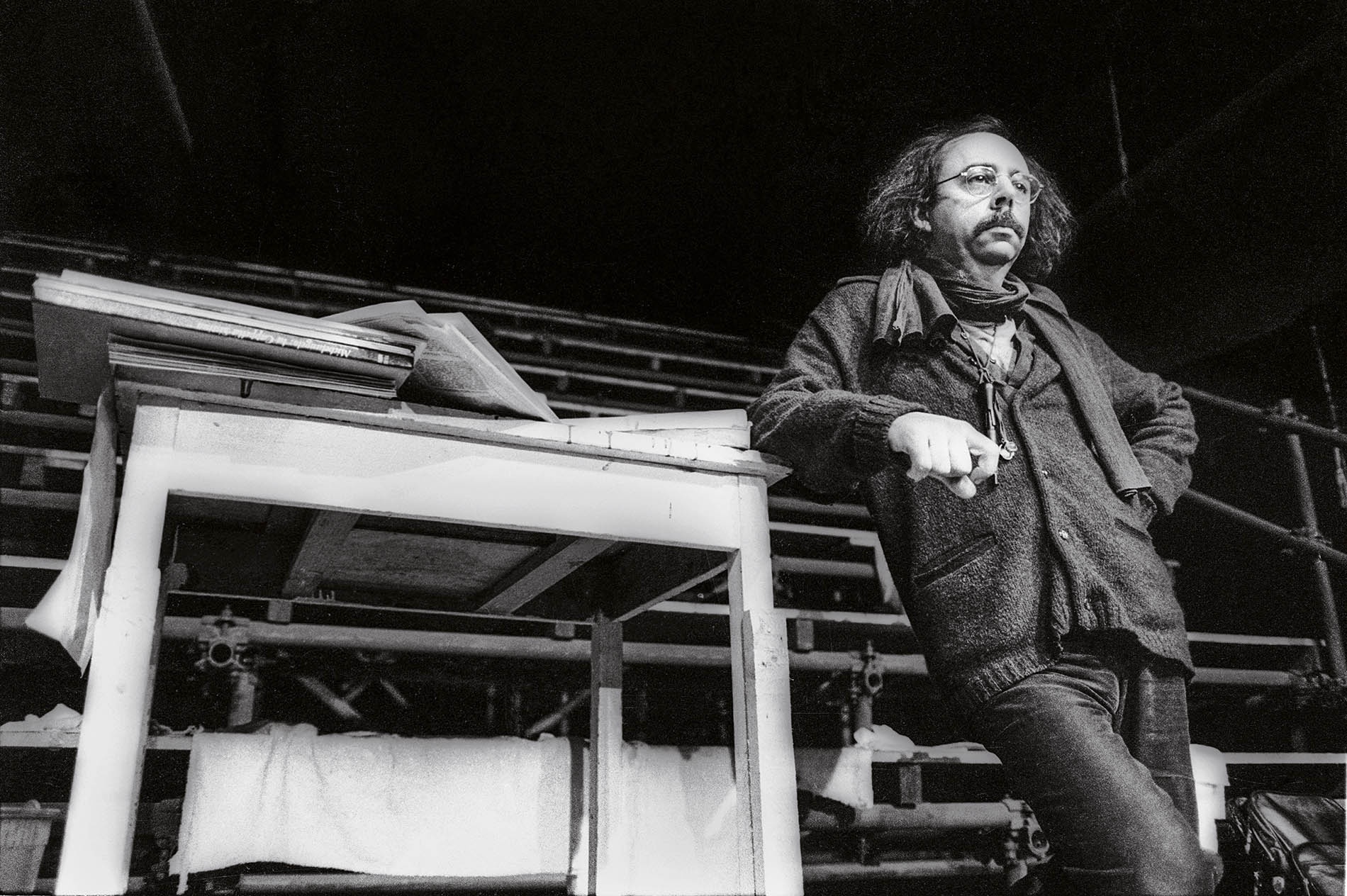

Starting in 1968, when Richard Foreman ’59 founded the Ontological-Hysteric theater, he conceived and directed more than 50 hypnotically bizarre, ritualistic productions, earning Foreman the multiple-Obie-winning reputation as one of the most singularly compelling auteurs of the downtown Manhattan theater scene. (His last show, Old-Fashioned Prostitutes (A True Romance), was staged in 2013.)

“He was cerebral but also was a terrific showman, the existentialist Ziegfeld,” says former chief New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley of Foreman, whose shows Brantley reviewed with enthusiasm from the ’90s into the 21st century. “His scenery and props looked like they’d been collected from a scavenger hunt, Brantley says, “and yet essentially his plays were all the same play, about the elusiveness of our own consciousness—how it’s always shifting and nothing stays fixed in the world.”

Foreman died in Manhattan on January 4 at the age of 87 from pneumonia, the New York Times reported. Wrote theater critic Helen Shaw in the New Yorker: “With the death of the director Richard Foreman...an era came to an end. You might define that era as a time of American aesthetic swagger, when artists such as Foreman, Mabou Mines, Meredith Monk, and Robert Wilson enjoyed international attention. ... But to me, and to many others, a whole half century was just . . . the era of Richard Foreman.”

It is hard to convey on the page the transfixing strangeness of Foreman’s entirely from-his-own-head productions, many of which this writer saw in the ’90s at the Ontological’s longtime home inside St. Mark’s in the Bowery, an East Village church long associated with avant-garde performance. The easiest shorthand for his shows, which almost always ran about 65 minutes, would be to say that they were like extremely vivid, sometimes sinister, sometimes dryly funny dreams—as full of philosophical declarations and ponderous silences as they were slapstick and wry one-liners. They often only took on meaning and coherence once you, the viewer, were halfway in, fully under their spells. To call Foreman’s sensibility a mashup of Ingmar Bergman’s existential moodiness, Woody Allen at his most absurdly despair-ridden, and Willy Wonka’s wacked-out dream factory wouldn’t be far off.

His work strongly influenced many strange-but-fun downtown theater directors and companies that came in his wake, such as Target Margin and Elevator Repair Service. “His shows were trippy, disjointed, and philosophical but also verbally gutsy and carnal,” says David Herskovitz, the founder of Target Margin, who assistant-directed for Foreman in the late ’80s and early ’90s and is a co-executor of Foreman’s literary estate. “They were very tight, intricate, detailed, and non-narrative, with no obvious story.” A typical bit of opaque but funny dialogue, Herskovitz recalled, was “What’s happening now?” “I’m happening—with my snacks. How about you?”

Foreman was born Edward Friedman in 1937 and adopted by a couple who raised him in the posh New York City suburb of Scarsdale, where, in high school, he quickly established himself as a “theatrical genius of an actor,” according to artist Richard Kostelanetz ’62, who said that Foreman, a few years his senior growing up, both urged him to apply to Brown and told him what to take when he got there. “He was like an older brother to me even though he was never very social.” Kostelanetz says the two ended up living for 34 years on the same block in Soho.

Foreman majored in English at Brown and got his MFA from the Yale School of Drama. After, in New York, he got a job through his father managing an apartment building while nearly getting a break as a playwright on Broadway. After it failed to pan out, he put on his first experimental play, Angelface, in a space belonging to the experimental filmmaker Jonas Mekas. (The two also made short films together in the 1970s.) That play was the beginning of the Ontological-Hysteric theater, which moved to its longtime home space at St. Mark’s in 1992. He gave his company its name, he told the New York Times in 1976, because his productions were “basically hysteric—repressed passions emerging as philosophical interactions.”

Foreman was married twice, first to the actor-turned-film-critic Amy Taubin from 1961 to 1972, then in 1988 to the artist and actor Kate Manheim, who performed in many of his works and served as a kind of muse to him. Foreman’s only immediate survivor, Manheim, on a brief call, said that Foreman was, to her, a combination of Casanova, Socrates, and Da Vinci, “because he was a jack of all trades.” She described him as “very charismatic and lovable” but also “introverted” and “often very mean—a long time ago in France, he stopped my performance in the middle of a show because he wasn’t happy with it. I had friends there, so it was embarrassing.”

Perhaps obsessiveness to the point of abrasiveness was inherent to an artist who was so singularly determined to alter his audience’s con-sciousness through what he put directly in front of them for just over an hour. “He did this not just through language but total staging,” says Jay Sanders, artistic director of NYC’s Artists Space, who was close with Foreman and interviewed him late last year on stage in one of Foreman’s final public appearances. “He showed that you can use the structure and form of your artwork to conjure otherworldly perceptions in the viewer. He did that better than anyone else.”