It's ten o'clock on a Sunday morning in the Diman House Lounge. The main attraction of the moment is the New York Times. Boys and girls scattered around the room swap sections back and forth and read choice items aloud to each other. A couple sitting on the couch makes a half-hearted stab at the crossword puzzle. A girl curled up in a corner chair with a philosophy text addresses the room at large, "Does anyone know the meaning of the word hylozoism?" No one is sure and one of the boys goes off to consult his dictionary.

Another boy drifts in and tries to promote a stoop ball game with little success. Nearly everyone intends to go to the library immediately, just as soon as they finish reading the Times. A few people are persuaded to play "just for a while" and they start to search for one of the dead tennis balls that are always around somewhere.

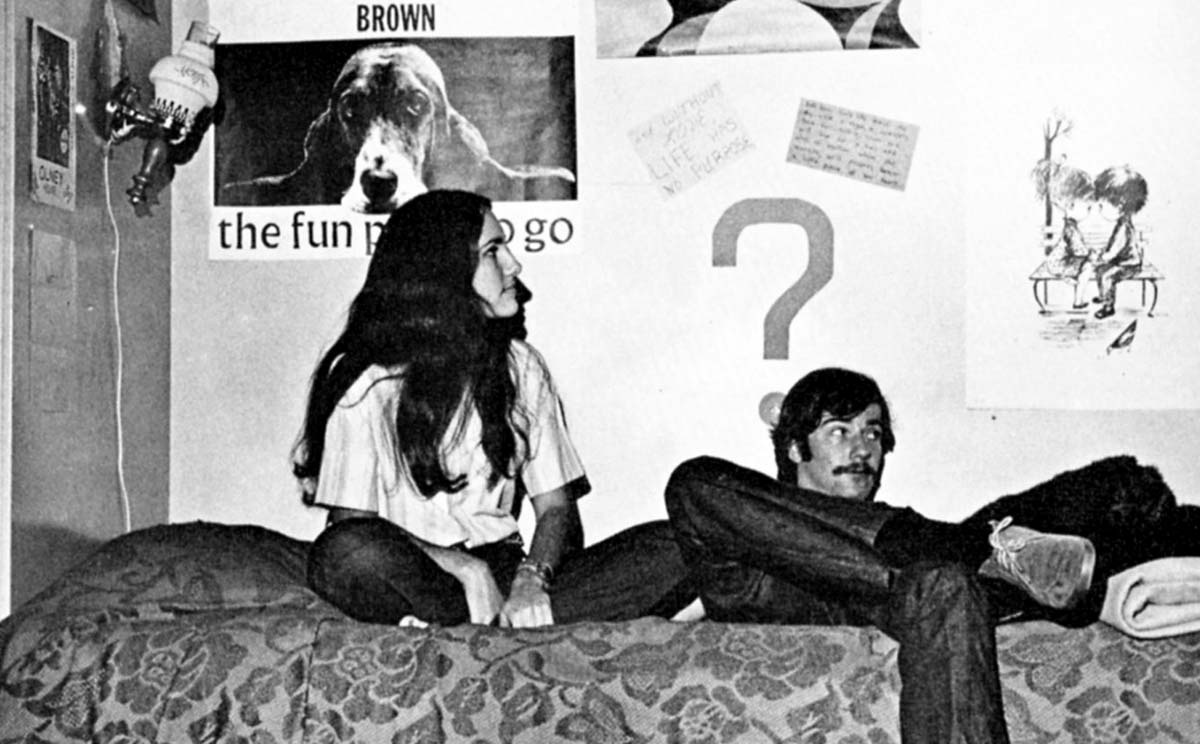

The coeducational housing committee report calls it "quality interaction between the sexes." The people who live here invariably describe it as "natural," "more natural," "normal," or occasionally not that big a thing.

What is "not that big a thing" is that this fall 57 Pembrokers moved into the top two floors of the Diman House-Alpha Pi Lam complex in the traditionally all-male Wriston Quad as part of a pilot project in coeducational housing. Sixty-one Brown men occupy the first two floors of the newly coed house.

The original impetus for the project came last year from the members of Alpha Pi Lam fraternity, whose first idea was to offer associate memberships to girls. After further study the plan evolved to include the Diman House wing of the complex, and both Pi Lam and Diman House agreed to suspend their identity as independent bodies within the University in favor of becoming one coed house. It was decided that the boys who already lived in the complex along with the Pi Lam pledges would draw lots to determine who would fill the spaces in the coed house. The girls were chosen by lottery from all those who applied.

The students wrote to other schools with co-educational housing and investigated the details of how such a project might work at Brown. When they first made their presentation to the Deans' Housing Committee last February, the students' advocacy was so enthusiastic that they converted several members who had previously been against the idea. One of these converts was alumni committee member. Knight Edwards '45.

"The matter of coeducational housing came up at the first meeting of the Deans' Housing Committee that I ever attended," recalls Edwards. "I came to that meeting with a relatively closed mind on the subject, thinking that it was not a good idea. But by the end of the meeting, after I had heard all the discussion, my mind was reasonably open. After that I talked to a number of students at Brown and other places. The more I thought about it, the more it seemed to me that there were really no arguments against it that made much sense."

Although Knight Edwards was not the only person who needed convincing when the coed housing plan was first proposed, by the time the girls moved in this September, it was hard to find anyone who would admit to thinking it was a bad idea. Pembroke Dean Charlotte Lowney '57, whose somewhat reluctant seal of approval on the project was announced in a Brown Daily Herald story under the headline, "Dean Lowney Acquiesces," now says that if she were a sophomore at Pembroke, she would probably apply to live in the coed dorm. Dean Lowney, who was acting dean of Pembroke last year in Dean Rosemary Pierrel's absence, says her initial misgivings stemmed more from a concern over Pembroke's coordinate status than from any objection to coed housing per se.

With the Corporation's approval of the pilot program. Brown joined some 200 colleges and universities that already have coed housing facilities, and although the decision to house boys and girls less than a green's length apart does not exactly place Brown at the frontiers of a revolution in life-styles, the coeducational dorm here is a lot more coeducational than many that go by that name. A number of the coed housing facilities across the country were built specifically for that purpose and consist of separate towers with a common lounge. But at Brown the girls and boys all live in one building separated only by stairs. There is freedom to move from one floor to another without benefit of bell desk, intercom announcements or anything except a polite concern for other people's privacy.

The same parietal hours are in effect in the coed house as in the rest of the University, but they are so liberal that no one can remember exactly when they begin and end. The students at the coed house make and enforce their own social rules within the guidelines of University policy, and the biggest issue so far has been whether to lock the main entrance doors at night as at Pembroke or leave them open as is the practice in the rest of Wriston Quad. Most of the boys, with an eye to the girls' safety, voted for locked doors. The majority of the girls, thinking of convenience and the two male floors between them and any potential intruder, opted for open doors. The doors remain unlocked.

The atmosphere of the coed house is noisy, relaxed and unsophisticated—it is, in the litany of the people who live there, a very natural environment. "It's just the opposite," says one of the coed house residents, "of meeting girls at one of those stilted mixers where all you can say is 'Where are you from? What's your major and what did you do last summer?'"

Freed from the tyranny of mixers, coed house residents get acquainted in other, more low-key ways. The "quality interaction" that the coed housing committee report talks about turns out to be things like:

• watching the seven o'clock news in the television lounge

• trying to induce one of the dozen or so resident kittens who skid up and down the halls to stand still long enough to be petted

• finishing off a table companion's leftovers at dinner

• learning how to ride a unicycle owned by one of the girls.

Nothing spectacular, as Director of Housing Robert Hill says, just people living in a building like people.

The formal activities the house plans for itself are equally unsensational. Scavenger hunts, pumpkin carving, pancake breakfasts, picnics, are some of the social highlights listed on the calendar in the front hall—all a far cry from the traditional loud-band weekend bash. As one of the boys remarked while he was surveying the coming month's calendar, "Somehow most of the social events that we plan turn out to be like family entertainment. Last year I would have felt silly carving a pumpkin, but now, when the girls are doing it too, I don't feel ridiculous, so 1 can relax and enjoy it."

The idea that coeducational housing fosters a family-type atmosphere where the residents come to regard one another as brothers and sisters has become almost a truism, but as truisms generally are, it appears to be true—at least up to a point. Since boys and girls are around each other all the time, it is impossible living in a coed dorm to regard the opposite sex as merely a Saturday night accessory. As Richard Abbot '71, puts it,

"It's great to have girls for friends rather than just as some strange creature that you see every Saturday night for a couple of hours. I don't have any sisters and so I only knew girls from going out on dates before and it seemed they were all pretty much alike. Living here, I have a much better idea of individual differences."

Rick Dentel '71, adds, "Another good thing about it is that while a lot of people won't date a girl unless she is relatively good-looking, in a coed house you begin to appreciate girls as people and you don't limit yourself in who you get to know. You see a completely different side of the girls when you are not in a dating situation. It does take away a lot of the mystery because you see them in ways that you would never expect to see them—like with their hair pinned up or with their room an absolute mess. I've never seen a messier room than one of those upstairs."

"Heterosexual reality" is the coed housing report's term for it, and there is some debate about whether or not it is a good thing.

The conflict between favoring romance and mystery between the sexes on one hand and everyday naturalness on the other is in many cases drawnup along generational lines. Parents lament the decline of the feminine mystique and daughters declare that they would rather be natural than mysterious. And although some parents might regret the lack of a sense of mystery between the sexes, at least a few take comfort in the resulting platonic atmosphere. "Don't worry," one mother assured her husband as they were moving their daughter into the coed house, "by the time everyone has been together for a month or so, they will probably all be so tired of each other that they wouldn't dream of dating anyone who lived here."

"Going around in curlers," seems to be the feminine mystique proponents' shorthand for not putting your best foot forward at all times with the opposite sex. But with the prevalence of straight hair styles, curlers are not that big an item around girls' dormitories anymore and the girls who do use them seem to have a fairly good idea of what the curly hair is for. As one of the coed house girls says, "I don't find myself being any sloppier because I'm living here, but neither do I worry about putting on my false eyelashes to go to dinner."

Most coed house residents insist that the proximity has not bred contempt, but it is true that some of them do feel more comfortable dating people who live elsewhere.

"You're kind of treading on thin ice," Rick Dentel says, "if you date someone living upstairs a lot because you see so much of them all the time. I think many guys would probably prefer dating someone who lives over at Pembroke because that's the kind of situation where you can isolate yourself afterwards and just see the girl when you want to see her. That's why a lot of people feel safer having 'just friends' relationships with the girls upstairs."

Dentel's view is by no means the unanimous opinion of the coed house residents, but it does appear to partially bear out the coed housing report's contention that eliminating the institutionalized barriers separating the sexes tends to increase friendships between the sexes rather than increasing sexual activity. In an appendix dealing with the psychological aspects of coeducational housing, the report says:

"The basic conflict concerning coeducational housing is the idea, generally left unspoken, that such a situation would foster undue sexual activity among the students involved." Though the report does not go on to define "undue sexual activity" or to distinguish it from any other sort, it does say that there would probably be less of it instead of more in a coeducational living situation.

This is impossible to prove one way or another, since there are no quantitative statistics on the subject, but impressionistic accounts of the "less sex" phenomenon have been offered from almost every place that has experimented with coeducational housing. Dr. Joseph Katz, a Stanford psychologist whose Incest Taboo theory has become an obligatory quote for anything written about coeducational living, says, in a recent article in Look magazine: "When a boy sees a girl every day, she becomes less of a sex object and more of a friend. When a boy lives close to a girl, the consequences of his actions are there. So he is more prudent."

Dr. Katz also points out that when students living in a coed dorm do become romantically and sexually involved with each other, the relationships are likely to be more stable and less manipulative than might otherwise be the case. Brown's housing director, Robert Hill, agrees with this sentiment.

"Some of the things that happen out of what may be transitory emotion are not so good," says Hill. "If a couple has an opportunity for a normal build-up of their association they are probably much better off. After all, men and women are going to live in society; this is all we have. They're not always going to be protected and sheltered."

Though Hill and other members of the Brown community who were involved with implementing the coed project express almost unqualified enthusiasm for it, they are careful to point out that coed housing should remain only one option in a flexible residence system. Coeducational living units, they say, are not for everyone. So far at Brown, they are not for freshmen, not for girls who don't have their parent's permission and especially not for anyone who isn't interested.

Concerning the future of coed housing on the campus. Dean of the College F. Donald Eckelmann says, "I imagine when the Deans' Housing Committee evaluates the project, it will come off very well. So the next question is, having tried this and having had it turn out well, now what? The first thing we will have to do is find out how much more interest there is."

A popular solution among students to "now what?" is to move a contingent of boys over to Pembroke, thereby easing the housing squeeze the girls have caused in the Quad. According to most people close to the question, this is not likely to happen next year. The matter of housing Brown students at Pembroke is more difficult than moving girls to Brown because of the implications raised concerning Pembroke's coordinate status. A Pembroke Study Committee has recently been created to investigate these and other implications of the coordinate system, so action on moving men to Pembroke will be deferred until that committee has had a chance to make its recommendations.

Although the Brown Daily Herald has editorially expressed the hope that the Pembroke Committee will not be used as a stalling device on such issues as coed housing, the University's interest in and awareness of what appears to be a nationwide trend toward coeducational housing is well evidenced by Dean Eckelmann's statement that, "No new residential unit can be designed at Brown without taking into consideration how it will serve both men and women." And according to Robert Hill, design for coeducation will not be the only difference in future residence halls.

"I think that whatever we build from now on will be a far cry from what we have now—long corridors with a room on either side and a community bath. Housing ought to be planned with the idea of fostering a sense of community among the residents." The coed housing report also stresses the importance of the physical design of housing, because, "the architectural setup by its very nature determines the kind of communication and interaction that takes place within a living unit."

That this is true is supported by the way the physical structure of the Diman House-Pi Lam complex has influenced living patterns in the coeducational housing pilot project. One of the few disappointments expressed by its residents is over the split that has developed between the people living in the two different wings of the building. This is probably partly because most of the boys were previous residents and had already formed associations in their own wing. But the main reason seems to be that casual social interaction revolves around the lounge, and each wing is served by a different lounge.

Questioned about the ideal physical layout for co-educational housing, most students say they would prefer suites or apartment-type facilities with boys and girls living in alternating apartments—commonly known as "random housing"— or, in other words, off campus-style living on campus.

This sort of residential unit would be an innovation on most campuses, just as coeducational housing of any kind is a fairly recent development. But as Robert Hill points out, it is well to remember that there is nothing new about men and v;omen living down the hall from each other in the rest of society.

As students come to regard their college experience less as a preparation for and postponement of the "real life" ahead and more as a very real arena for encountering life, there is growing agreement that it makes no sense to ask them to defer the choices and responsibilities that are so large a part of becoming a person in control of his own life.

Martha Lear says in an August Ladies Home Journal article:

"It is impossible to visit a coed residence without sensing the benign revolution in progress. It is, I am convinced, light years better, more intelligent and more morally elegant than the ambience of my own undergraduate days, when girls entertaining male visitors at high noon were instructed to keep their doors wide open and both feet on the ground at all times—and the panty raid, coming each spring like a virus, was still a reasonable form of communication between the sexes." A.B.

From the December 1969 BAM