A few years ago, while living as an anthropologist in the Kingdom of Morocco, I tried to get back in shape. I might have visited the several health clubs located throughout Rabat, the nation's capital, which has no shortage of modern services for the cosmopolitan elite. But I have always preferred to take my exercise in the fresh air or at least, when urban exhaust makes that impossible, outside.

The first time I ventured to the shoreline I barely noticed the ocean at all. I was still getting my running legs back, so most of my energy was devoted to staying upright. And, being a dutiful anthropologist, I was more interested in the social scene: couples out for an evening stroll, students studying for university exams, boys playing soccer on any tuft of grass big enough to mark out a field.

Beyond the people, though, what I saw most was the garbage; it was piled by the roadside, tangled in the scrub brush, blowing in the wind, sweeping in from the sea, emerging from pipes as raw sewage, and pouring forth as smoke from buses and trucks that clogged the coastal road.

"Let's write a letter to the King," my visiting brother-in-law would later joke as we walked along an empty beach strewn with litter, "and tell him to clean up this place." Since then, I have often thought about my initial confrontation with Moroccan garbage and what, to North American eyes, can appear to be its excessive and disorderly public distribution. As anthropologists have long noted, how we define, avoid, and treat our garbage reveals a great deal about us. And so, rather than simply being appalled, I began to consider what Moroccan garbage might teach me.

Let us put aside immediately all tired notions about a lack of cleanliness and hygiene in underdeveloped countries. To the contrary, Moroccan garbage is so evident in public largely because it is so unacceptable in private. Garbage appears to be everywhere precisely because, like many of us, Moroccans don't want to store it permanently in their homes, which tend to be immaculate on the inside.

Moroccans do not necessarily lack the will to keep their public spaces clean, but Morocco is surely without the infrastructure to make that happen. In the end, the major difference between Moroccan public garbage and our own may be that we do a much better job of hiding it. From this perspective, why shouldn't we think of public garbage in Morocco as being, above all, honest? What would we learn about ourselves if we dumped our mounting waste on our front lawns, or let it rot in our gutters, instead of having it disappear each week?

It took me just a week of running before I saw through the veneer of refuse to the vast beauty of the coastline, before I heard the thunderous symphony of the waves over the constant droning of diesel engines. Soon I barely noticed the garbage at all. Ignoring garbage might not be the best way to cope with what is a real problem in Morocco and in much of the developing world. But is this so different from what I would do, even more effectively, when I returned home to a country that produces more than its fair share of the stuff?

Oren Kosansky is an assistant professor of anthropology at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon.

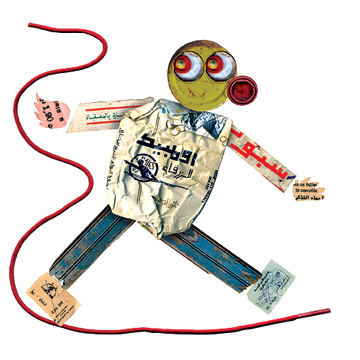

Illustration by David Goldin.