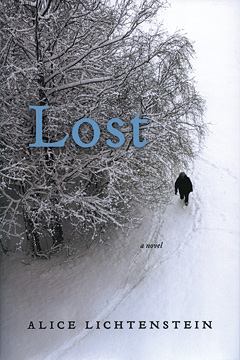

Lost by Alice Lichtenstein '79 (Scribner).

The proverb "The road to hell is paved with good intentions" dates to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote, "L'enfer est plein de bonnes volontés et desirs." ("Hell is full of good wishes and desires.") Bernard knew a thing or two about good intentions and bad consequences: his preaching sparked the second—and utterly disastrous—Crusade, which resulted in a bloodbath.

The disasters in Alice Lichtenstein's haunting first novel, Lost, are on a more intimate scale than the Crusades, but they feel just as tragic. A twelve-year-old boy named Corey Byer accidentally ignites a stash of cigarette lighters, killing his brother and burning his aunt-and-uncle's house to the ground. Rendered mute by guilt and branded a firebug, Corey is banished to his grandparents' farm, "because no one else in the family could stand the sight of him," the boy reasons. "He was the scar that reminded them of pain."

Living in the same rural patch of New Jersey is Susan Hunsinger, a middle-aged woman who blames herself for her husband, Christopher's, dementia. A microbiologist specializing in cell regeneration, she fears she caused his Alzheimer's by having an affair with a colleague. "Wasn't it possible that in that crucible of rage, Christopher's cells had rattled off their tracks, lost their bearings, no longer able to determine the good fight?" she suggests to her therapist.

Stoically, Susan has put her professional and emotional life on hold to care for Christopher. To distance him from painful memories of their home in Princeton—a house he, an architect, designed and filled with friends—she moves him upstate to a nondescript house in the country. The plan backfires. In this barren landscape Christopher may not be enraged by memories, but he is lost without guideposts. And the task Susan has taken upon herself is overwhelming. After he has a fit one morning and forces himself on her sexually, she leaves him sleeping while she walks down the road for a few minutes. When she returns, he is gone. She traces the tracks of his sneakers across the snow to the ice and grit in the road, where they vanish.

The task of finding Christopher falls to Jeff Herdman, a Vietnam vet and social worker who brings together these two narratives. His specialty is fire and safety, and he is preoccupied by the case of Corey Byer even as he supervises the doomed search for Christopher Hunsinger. The volunteer searchers destroy Christopher's tracks as they trample the snow looking for him. What we know from the start is that Corey will be the one to find Christopher's body.

Lichtenstein weaves these stories into a compact novel of guilt and recrimination. The plot's multiple strands loop over and around one another, sometimes lyrically, sometimes ominously, but always urgently. The characters carry their pasts in their pockets like touchstones they'd be better off leaving on the nightstand but can't seem to stop fingering.

And then, out of nowhere, they shake those memories loose, freeing themselves to start over in ways you might never imagine, and leaving you with the memories to finger.

Charlotte Bruce Harvey '78 is the BAM managing editor.