When Rachel Morello-Frosch joined Brown’s Center for Environmental Studies (CES) as an assistant professor in the early 2000s, she was nervous to tell her new boss, director Harold Ward, that she’d recently been inducted into the so-called Junk Science Hall of Fame — an industry blacklist for scientists studying toxic chemicals. “He just laughed in his understated way and said, ‘Don’t worry about that.’” Morello-Frosch remembers. “‘That’s a badge of honor—you should put that on your application for tenure!’”

That moment is typical of Ward’s unwavering support for his students and colleagues, as well as his subtly subversive way of challenging authority to advance environmental change. Over more than 40 years, Ward helped pioneer the field of environmental studies (ES) and mentored scientists and activists who have carried his legacy far beyond College Hill. “I would not be where I am today if Harold hadn’t recruited me and given me support and space to do community-based, participatory science,” says Morello-Frosch, now leading an environmental health and justice program at UC Berkeley.

Nor is she alone. Ward, who died December 4, was far ahead of his time in pursuing an interdisciplinary approach to ES that combined hands-on learning with real-world impact. Through the Urban Environmental Lab (UEL) and initiatives like Brown is Green, he championed sustainability long before it became a national trend. His research influenced state laws still on the books today. “He wasn’t a big chest-beating extrovert, yet he accomplished so many things just by being incredibly smart and diligent,” says Kurt Teichert, senior lecturer in Environment and Society, who first arrived in 1990 to help Ward overhaul campus energy usage through Brown is Green.

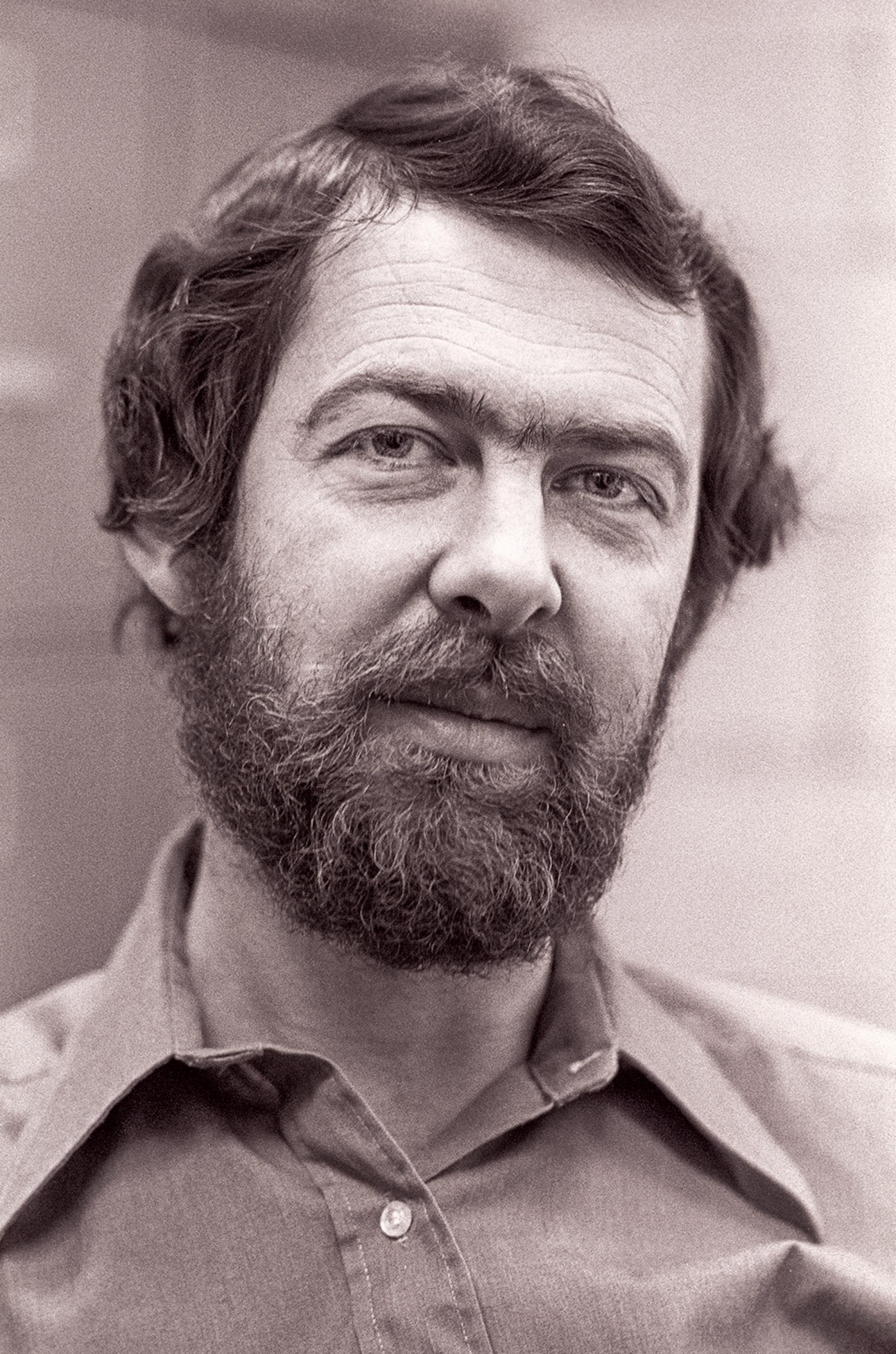

“He was a very, very kind person,” says his wife, Selma Moss-Ward. “He wasn’t exactly sweet to his students, but they developed a great deal of affection for him because he would listen to them and do things on their behalf —constantly finding them jobs or connecting them with research projects.” Students compared him to Professor Dumbledore or Obi-Wan Kenobi, a wise, slightly gruff mentor with a bushy white beard and a warm heart.

“In a word, Harold was magnanimous,” says Nan Jenks-Jay, professor emerita at Middlebury, who looked to Ward as a mentor working alongside him through the Northeast Environmental Studies (NEES) consortium in the 1990s. “Harold became an ambassador supporting colleagues across the country,” she says. “More than once, he buoyed us up when we were met with daunting institutional predicaments.” Ward was “the patriarch of interdisciplinary studies related to protecting the environment,” adds Eric Pallant, who launched the ES program at Allegheny College and learned from Ward as a visiting professor at Brown.

Ward’s approach to conservation was rooted in his childhood on a subsistence farm in southern Illinois with no electricity and little money. “He caught on to the idea of recycling early because you didn’t throw stuff out—you made it last or found a new use for it,” says Moss-Ward. After studying chemistry at Southern Illinois University, he got a PhD at MIT and completed a postdoc at Oxford before coming in Brown as a chemistry professor in 1963, the same year Congress passed its first air quality law.

Earning tenure quickly, Ward’s interests shifted toward practical application of his knowledge. After fielding numerous calls from Providence residents concerned about toxins, he took advantage of an Environmental Protection Agency program to earn a law degree at Harvard, returning to Brown in 1978 to found the CES. Soon after, Ward transformed the Lucian Sharpe–designed Carriage House at 135 Angell Street into the UEL, securing funding from the Mellon Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy. It became one of the first “green” buildings at a major university. Students lived there and in two neighboring dorms, tending community gardens and experimenting with ways to conserve energy and water while reducing waste.

In the 1980s, Ward and his students launched Brown’s first recycling program, placing barrels outside the UEL that directly inspired Rhode Island’s state recycling laws. Students from CES monitored the state’s progress, building real-world experience alongside environmental advocacy.

As president of Ecology Action of Rhode Island, and later chair of the state branch of the Conservation Law Foundation, Ward frequently testified as an expert at the state house, as well as working with state officials to craft laws and policy on recycling, lead toxicity, air quality, and watershed management. “He was a consistent force for decades,” says former department of environmental management official Bob Vanderslice. “If he was your friend, he had your back and wasn’t going away. If you were on the other side, he wasn’t going away either.”

Ward frequently involved students, helping set them up with research projects and internships that would have direct impact on the local and state environment. “Harold had high standards—for himself and others,” says Chip Giller, who worked as his teaching assistant in the early ’90s, helped with state policy projects, and later founded the environmental publication Grist. “He encouraged you by trusting you fully—you wanted to push yourself to meet those broad goals.”

Despite his institutional savvy, Ward maintained a counter-cultural spirit, sponsoring informal “PCBs” (Pizza, Conversation, and Beverages) and “Soup Seminars” gatherings at the UEL. At NEES meetings, Ward fostered a similarly egalitarian spirit, with no dues or formal presentations, just an informal space for conversation and support. “Without ever being pushy, he had this quiet presence—you felt it when he was in the room,” recalls Pallant. “When he finally spoke, it was intellectually sound and utterly persuasive.”

One of Ward’s biggest frustrations was his inability to turn ES into a full department. He came close several times, but changes in administration sidetracked his plans. In the early 2000s, he fiercely opposed plans to move the UEL to make way for new labs, enlisting students and the Providence Preservation Society for the fight. “In the end, the building was saved, but it was excruciating for him,” Moss-Ward says.

After becoming emeritus, Ward turned his South County home along the Wood River into a sustainability showcase, becoming a certified master gardener and working to graft more than 50 varieties of heirloom tomatoes to disease-resistant rootstocks, a feat that earned mention in the New York Times. Ward’s legacy lives on through the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society (IBES). “Much of IBES’s success owes itself to Harold and the community of scholars he nurtured,” says IBES director Kim Cobb. At the Institute’s 10th anniversary celebration, attended by nearly 200 alumni, faculty, and community partners, Cobb launched the annual Harold Ward Prize for Community Engagement, to be presented to a senior. Many attendees shared memories of Ward, collected into a commemorative book, testifying to the profound influence he had on their lives and careers. “He was so happy people remembered him and valued what he had done,” says Moss-Ward. “He was over the moon.”

He is survived by Moss-Ward, two children, and numerous environmentalists whom he helped to create.