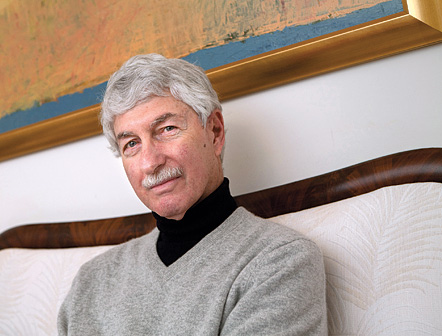

In his latest book, Morning, Noon, and Night: Finding the Meaning of Life's Stages Through Books, professor of comparative literature Arnold Weinstein explores what some of the greatest works of fiction have to tell us about the process of aging.

WEINSTEIN Writing about growing old is something that I've wanted to do for a long time. It's not a subject you could teach in college. Undergraduates have zero interest in aging. But some of the discussions in this book led me to talk about my own experiences, memories, and dreams. During the writing of this book I felt like I got a lot older than when I started, so I had more things to say. I started thinking about the book when I was 65. I'm 70 now. I've been taking a crash course on the subject of aging.

BAM What does King Lear tell us about aging?

WEINSTEIN I quote Freud's quote about Lear all the time—"to make friends with the necessity of dying." He said that's what Shakespeare's play shows us. Lear thinks that his power is timeless. The fool tells him repeatedly it isn't. The play teaches us that the old will yield the stage to the next generation, whether willingly or not.

BAM And yet you also write about the older generation refusing to let the younger one rise.

WEINSTEIN Every one of Kafka's stories is in some sense about a powerful father crushing us. It's about the impossibility of rising to maturity. But even in liberal writers like Ibsen, that same story gets told in play after play. Children seem sacrificed over and over. We ask our young to go out and fight wars for us. It's not simply a kind of diseased psychological state. It's the way in which a culture's authority gets enacted.

BAM What do you mean when you say that literature lets us "reclaim" our lives?

WEINSTEIN In general, I think we have a great deal of trouble understanding the shape or pattern of our own lives, partly because perception is keyed to momentary experience. I think we're so busy living we often have trouble achieving that type of analysis or taking measure. Art in all its forms and media helps us to have a picture of our own lives. Every book that we read is in some sense a mirror. Reading is always gauging what is worth discovering in the book against our own lives.

BAM You don't have much that's positive to say about getting older.

WEINSTEIN The view that we come to wisdom as we get older is overdone. It's a sappy view. It's often sentimental, and I don't know how many old people subscribe very passionately to it. I think getting old is losing a lot of not just your authority but your resources, your assets, your strengths. The Old Man and the Sea is about a man who achieves something great as his last exploit, but the notion that we've achieved great wisdom or maturity is not true.

BAM So is there anything we gain as we age?

WEINSTEIN I call it fourth-dimensional vision. It's very painful when people see their parents dying and all of a sudden have to come to terms with it. But it occurred to me that that also has a reverse dimensionality—if we can see people in time, we acquire a richer sense of, yes, they are eventually going to die, but they were also young at one point. Proust is marvelous about this. He has his narrator [in In Search of Lost Time] encounter these women he loved as a child, and he says, "What I value in them is not what they are now, but how much they meant to me back then in the past." It makes for a more generous kind of vision. —L.G.