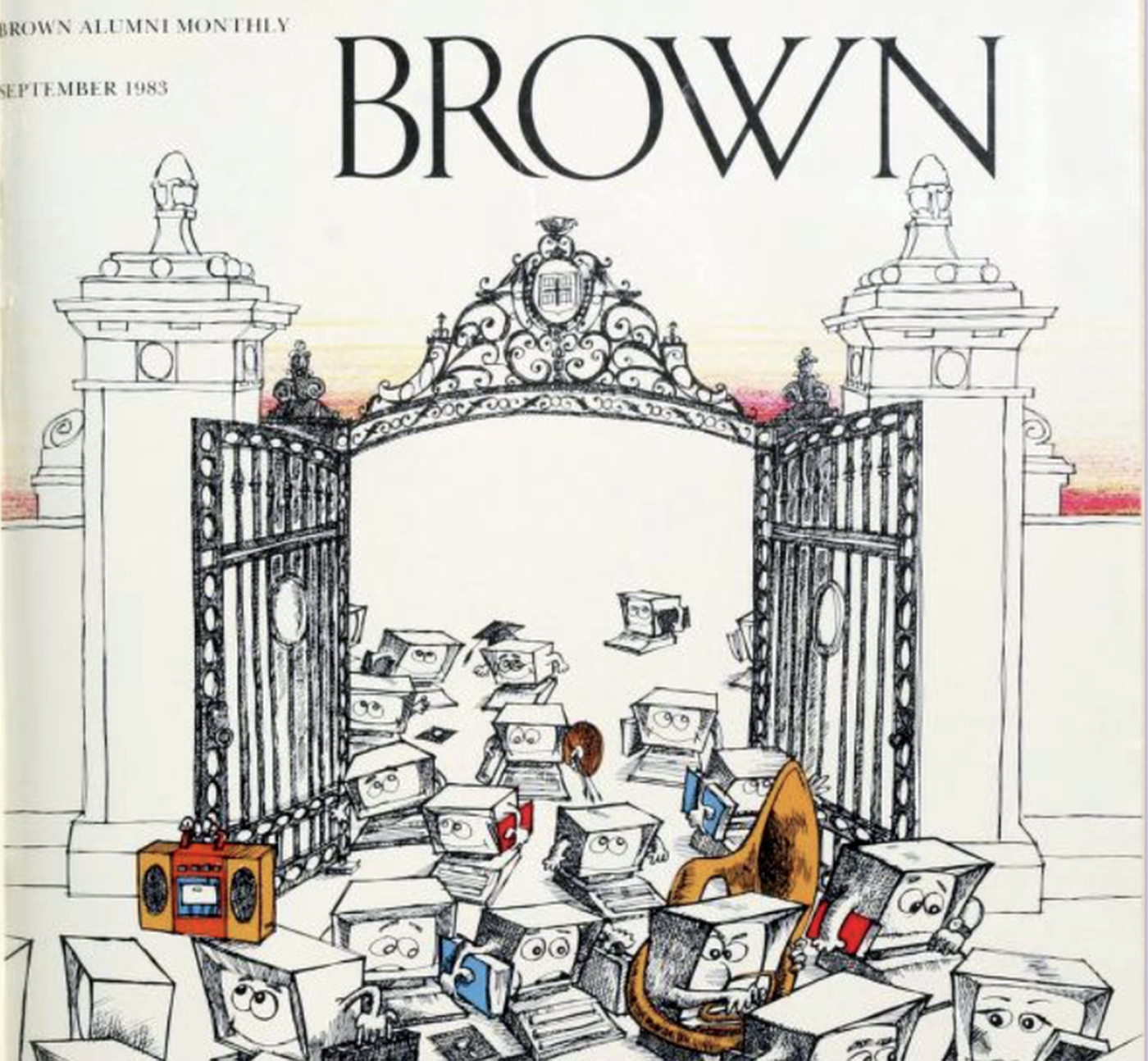

Johann Gutenberg detonated the information explosion 500 years ago, when the first pages of the Bible rolled off his printing press. The implications of moveable type were enormous, and no one could foresee the consequences of that one moment in the history of technology.

Today Brown is poised to begin an experiment that may have as equally strong an impact on the life of the mind as the Gutenberg press. The University has embarked on a proposal to spend $50 to $70 million in the next six years to equip each faculty member, student, administrator, and staff member on campus with a powerful new type of personal computer (BAM, May).

"We are looking at a massive change in intellectual society," says Andries van Dam, chairman of the computer science department and one of the architects of the proposal. "If you aren't scared about the implications of this change, how it's going to revolutionize teaching and research, you're not thinking."

The University community has had several months to think about the computer proposal and how it is going to affect the quality of education and the quality of life at Brown. Many of the questions that are being raised have no answers—and won't for years, even generations—and as van Dam says, "We don't even know what most of the questions are.

"It's 1905 and you have seen your first horseless carriage drive down the street" he offers as analogy. "Your job is to plan the impact of this machine on the American economy, society, infrastructure. Think about what people must have felt like, the predictions they must have made. We're not the inventors of the new computer technology, but we're among the first wave of ardent enthusiasts. I feel we don't know anything about the impact at this point."

Perhaps the first question is: Why now? What is it that makes the time ripe to attempt an experiment of this scale and nature?

"It's a question of what's happening in the world out there," explains van Dam. "There is a growing awareness among computer manufacturers that workstations are the wave of the future."

"We have the opportunity to shape the new technology and to do it in a way that is appropriate to Brown"

The scholar's workstation is a package of computing tools that lies at the heart of the project. In the beginning, the workstations will provide secretarial functions, but soon, as libraries and other databases become accessible to computers, the workstations could be used more like research assistants. "We've been working longer on the workstation than most schools. We have a track record in using them, not just research on them. We're the only ones with a teaching lab like the Gould Lab (BAM, November 1982), and we've been pioneers in the graphics area, which is an important part of what workstations are all about. No one else has even a year's worth of experience using workstations in the classroom setting, and although we have only a year's worth—which is minimal—it's the old story that in the land of the blind, the one-eyed is king. We are the one-eyed in this land-of-blind use of workstations in the classroom."

That one year of experience has made Brown look good to computer industries willing to donate money and machines (see sidebar). "We're sort of the young turks," says van Dam. "The companies come here, and we blow their socks off with all kinds of stuff they haven't seen at other major schools."

There is no doubt in anyone's mind that computers are becoming—have become—a presence in education that can no longer be ignored. Students are already bringing their personal computers to campus and asking where to plug them in. William Shipp, associate provost for computing, says, "There is a belief among zealots that this is going to happen no matter what we do. If you accept that fact and realize that it has the potential for major social change—both positive and negative—and if you realize that many schools with different goals may be shaping the technology, you come to the conclusion that we have the opportunity to shape the new technology, too, and to do it in a way that's really appropriate to Brown."

"If we don't plan for it," adds head librarian Merrily Taylor, "it's going to happen anyway, and in a haphazard way. Things may happen that wouldn't necessarily be good for a liberal arts environment. I am not even sure I could speculate what some of those things are. But think of the way people grumble about computers in business, or billing—you are always being given the excuse that things can't be done in a certain way 'because the computer won't let us.' Things get done the way the computer wanted them done, not the way you wanted them done. I think Brown wants to get in and control the process so that we use the computers to do what we want them to do, not have someone else from the outside world develop a system that we would then have to adapt to our own needs."

Another reason to face the computer issue now is that the demand for computing on campus is growing at a phenomenal rate. "Last year the growth rate for research and administration needs was 80 percent," Shipp says. And students were camping out in the computer science department for days hoping to sign up for CS 11—introductory programming. "If we think about how we can meet the growing demands while coping with the dissatisfaction with the style of computing we have now, we know we have a dilemma. Then if we know there is something that has greater promise coming down the road, it makes sense to seize the opportunity."

"It's a wave," says van Dam. "You either ride it or it washes over you and you drown. We've done some things that make us think that we can make a major qualitative improvement in the life of students, scholars, and teachers."

"If we don't plan for the new technology, it will happen anyway and in a haphazard way"

"That's what we really want to do. What are the negative things going to be? What are the side effects? It's like having a new drug. You know there are going to be some things that aren't going to be right, but you want to find out about them. There's no point in saying, 'Well, gee, this is going to be scary and that could be terrible.' We want to know what the problems are."

Another element in the 'Why now?' question is the Edsel problem. Since computer technology is advancing at such a rapid pace, how can we be assured that the machines we invest in today aren't obsolete tomorrow or next week? "It's a serious problem," admits van Dam. "But nothing you can do will stop technology. It just keeps pushing. So let's figure out the best possible thing we can do—especially in helping students so they're not chained to something they buy in their freshmen year that everybody snickers at by the time they're seniors. Maybe when you buy something from the manufacturer in the future what you will do is buy an insurance policy that guarantees, in the event the machine becomes completely obsolete, you'll get 30 percent of the purchase price back. There will be lots of unanswerable questions, but at least if we start asking them, maybe we can come up with technological solutions."

The question that has fascinated van Dam since the mid-1980s is: "What do scholars do? What do they want computers for beyond word-processing functions? I don't want to denigrate word processing, but we've been doing that for fifteen years and it's not what workstations are going to be used for. They are going to be used for storing data, for making connections, for allowing people to make the connections—those associations that human beings do so well, where one thing will trigger something else that will make you think of yet something else. That's what excites me the most, the intellectual stepladders. We will now have what the propaganda has been promising: computers as intellectual helpmates."

The computer will lessen what van Dam calls the "dog work" of research: the physical hunting through libraries for books, the re-typing of bibliographies, rewriting drafts. And for specialized fields—mathematics, engineering, classical languages, Egyptology—where symbols other than the standard alphabet are used, advanced graphics can provide online source materials. If the basic drudge work is alleviated, the possibility for increased productivity emerges—for better or worse.

"There is a danger in scholarship of people producing too much," says Roger Henkle, chairman of the English department. "There is already too much produced in my field [the nineteenth-century novel], but it's true all through the profession that there are people who haven't carefully edited or thought through what they want to say. With the ability to store and manipulate a lot of material, the computer can produce scholarship that is basically a collection of data. Because you can absorb and manipulate material more readily, in some cases there is a temptation to produce."

Henkle, who does intend to use the computer, says he has resisted it thus far because he didn't want to take the time to learn it and didnt feel it would save that much time with his research. He also resisted for "semi-philosophical" reasons, and voices a concern heard frequently among humanities scholars. "People in my profession revere the book, and the computer signifies a kind of alienation from the book. The book itself is an object of crucial importance. The way you handle it, the way you deal with a book is different from how you deal with computer material... that sense of reading backwards and forwards, browsing through it. One of the things that we have to talk about when we consider the great advantages of the computer for research is that one of the ways people end up discovering things is by browsing through the stacks, and that won't be possible, no matter how many books are catalogued on the computer. The sense of the book as an artifact that carries a great deal of prestige and the tradition behind the book are something the computer won't propagate."

Merrily Taylor, who like Henkle served as a consultant on the original proposal, says, "We want to make sure we keep the virtues of the older systems while approaching and moving into the new world. It's important that people realize it's not a tradeoff of technology for tradition. I don't think it's practicable or desirable to put War and Peace on a computer or to read it on a CRT, but maybe you could do a lot of exciting things with manipulating the novel to discover why Tolstoy used a particular verb far more than any other, for instance. But there are still going to be lots of situations where the plain old book is going to be the best way to store certain kinds of information.

"If the university has a basic commodity that it both trades in and lives off, it's information," she continues. "You can't conceive of a place like Brown without its library. If the library was gone, would you still have a university? We're a fundamental resource." It's a resource that, with computerization, may no longer be free, which raises provocative questions. "If people are going to continue to do research and pass it on to students, they have to have access to the information and they have to have it in a way that is more or less democratic. You can't say to certain segments of the University, 'You have access, but you don't.'

“The scholar's workstation is a teaching tool of unrivaled dimensions”

"Let me give you an example. It used to be that a library would buy something like Chemical Abstracts and pay $2,500 a year for the subscription and it would be available in the reference room. If you wanted to use it, you would walk in and use it—even if you used it ten times a day there was no cost to you. Now if you want to use Chem Abstracts online, there is a connect dialing charge, a citation charge, a charge for printing out your citations. Someone has to pay for that. Right now, the library is. But as more reference materials are put online and become available in that form, we will have to look at the whole philosophical issue. A lot of this information is now being provided by the profit sector—they are doing it for money. It's not in the hand of higher education or the non-profit sector. What does that really mean when we start looking at an information society where there will be haves and have-nots depending on whether you can pay for the information you need?"

Taylor adds that one of the exciting aspects of the computer experiment is the prospect that Brown and other universities might be able to cooperate on acquiring databases of their own and mount them on university computers. "This would make the information accessible to people in the university community without any of the charges."

"We in the humanities are, and will continue to be, very library-reliant," says art professor Kermit Champa. "The technical disciplines work for the most part with current periodical literature, which goes online very easily. But those of us who work with out-of-print antiquarian documentary materials are working with materials that will probably never be able to be transferred because of the man-hours necessary to do so."

Another practical concern relating to time is voiced by Marc Parmentier, associate professor of geological sciences. "How are faculty members going to be able to take the time to develop the programs they will be using in their classes? If we are supposed to do that in the summer, when will we have time to do our research? There may be a degradation in the quality of teaching in the short term, and research in the long term."

The scholar's workstation is, in van Dam's words, "a teaching tool of unrivalled dimensions. It's like having the best of television, transparency projectors, and chalkboards; but it's much more malleable than any of those, and the student can control it."

Not only will the workstation be flexible, it will be amazingly powerful: "Each of the new Apollos in the Gould Lab is more powerful than the central time-sharing computer that we had in the computing lab for the entire University in the mid-60s."

Admittedly a zealot, van Dam believes the possibilities of using the computer as an enhancement for traditional means of teaching are endlessly exciting. He points to the poetry project sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities that he "spawned at Brown in 1975." This experiment made use of "hypertext," networks of cross-referenced, linked manuscripts with their associated marginal notes, key-worded passages, exchanges with other students, and other references. A student could look at the screen and see the original poem as well as comments made by the professor and fellow classmates. "One of the things I was just charmed by in the NEH poetry experiment," says van Dam, "was that people were working much more together because of the electronic medium. They were writing to each other, marking up the text, then someone else would read the comments and write comments on the comments. There were whole dialogues going on; it was neat, really fun." In addition to the increased inter-communication, students who were working on the computer wrote three times as much as did those in two control sections of the course, with no decrease in quality. "People admitted that they really got into it and it was miserably inconvenient. You had to sign up for your hours and hope that the machine was up. It's not like sitting at your workstation at two in the morning and when you get an inspiration, you can quickly bang something out."

Henkle is "interested in using the computer in my journalistic writing class. Most of what we're doing involves rhetorical emphasis, moving things around, handling material, rearranging your examples; and it seems to me the computer will be particularly useful for that purpose." He thinks, though, that until every student is equipped with his own computer, there may be problems teaching writing on the computer.

Mary Lewis, an associate professor of music, has been doing her research with the help of computers for years, and she says that "to say I am enthusiastic about this project is to put it mildly. Hypertext is one of the most exciting concepts to come along... that and the increased communications capabilities of computers are really valuable."

"One thing we'd like to see in my field is the development of a music editor, which could edit music the way you do text. It seems to me easy to integrate graphics and text. Once we can run music [through a computer] the way you do words, the next step would be the development of a music skills laboratory, where we could use the workstations to develop music skills—composition skills, harmony, music reading; all the fundamental skills of musical literacy that go beyond theory.

"If a keyboard could be developed like a piano keyboard, where you could play and the notes would be typed right in, students could upgrade their skills, work in a self-paced way and make the work go much faster. It would also free up the faculty to teach more creatively."

Lewis says that the computer will make music composition essentially a whole new field. "Just copying out scores is expensive and time-consuming. It could take so much of the drudgery out of it if you could do it on computer. I've seen programs where you can hit a button and the entire score can go up or down a fifth. As people use these machines and become aware of the potential, they will change our work habits. The ease and speed of learning on these workstations is amazing."

Dean of the College Harriet Sheridan thinks the computer will "allow much more diversity and flexibility in teaching techniques. It will provide a changed environment that will heighten our own consciousness about what we do. The trouble with educational programs is that faculty get a Ph.D. and start teaching and continue to teach more or less in the same way if they were successful to begin with. Yet students and their needs change and we don't. I think the computer will contribute to that change. I think the greatest danger the human mind suffers is a boredom of getting so routinized, so used to doing the same thing that you stop really thinking about what you are doing. Change is an important factor in keeping an intellectual alive."

As the University becomes more "wired," the uses for cable and video will grow accordingly. Once everyone is hooked up to the network, students will be able to use their workstations to review lectures and labs. "There are lots of uses for cables in universities," explains Sally Kingsbury, coordinator of Brown's media services. "At MIT, for example, if a professor gives a pre-exam workshop it can be televised live and students can call up from all over campus and ask questions. Taping science labs is also useful, because it allows you to see processes—for example, surgical procedures—more clearly. Video is an educational tool that can slow down or speed up processes. It's another way of looking at yourself. You can use it in linguistics or in sports. In the future we will be able to call up visual information and give students more varied kinds of illustrations to show them more clearly what they are trying to learn.

"There's also the possibility of being able to take classes at other schools via satellite. Or, if you were taking an archaeology class, someone could be at the actual dig. Video extends the boundaries of education. Thinking in a visual way will become more of a necessity. Media-related professions are expanding geometrically, so it's good for students to become familiar with the medium."

Some classes at Brown are already being taped and put in the archives at media services for students to come and review. Will this mean that students will attend their classes less frequently, if they know they can catch up later by using a tape? Will social and scholastic interaction be lessened if a student can sit in a dorm room and do most of the required coursework without leaving the dorm? "I don't see the computer as replacing the human component that a classroom association involves," says Sheridan. "It reinforces and complements the classroom setting. I think we have to guard against the rapture of the machine, in which the human being seems much less efficient and cogent than the carefully constructed program. Something very important in the lack of cogency and efficiency in the human delivery can be lost. That whole sense that students should be picking up of the way in which the mind works—both its fallibility and its triumph—may no longer be apparent. I think students slowly and imperceptibly build up their notion of what people are like and what faculty they admire are like from that kind of association—as much from the stammering and the groping as from anything that's carefully organized. That human development, that perception of what human nature is like, is a factor. We don't know how steady use of the computer is going to affect that kind of understanding."

“The computer will allow much more diversity and flexibility in teaching techniques”

"It's conceivable that the computer could create a kind of atmosphere where the seminar workshop situation is diminished," offers Henkle. "One of the most important things we teach in college is the ability to articulate in a group of people where there is dialogue, confrontation, interrogation. You have to have the poise to handle yourself verbally, and the need for that is not going to go away no matter how many computers you have. Conceivably, it's going to be very easy for the shy person to avoid those situations if he can." But Lewis thinks that "people who have trouble interacting anyway will get into using [and abusing] the computer. It will increase communication rather than decrease it. I didn't find that we saw less of each other when I was at MIT. There is the horrible vision of students locked in with their studies, but even the worst computer jocks would group together. The introverted, non-social computer nerd is almost an exception. I think people will still want to talk to each other—in many ways, carrels in the library are somewhat more isolated. You can't reach people when they are sitting at those carrels. If you're working on a computer, you're immediately in touch."

“This project has the potential to transform the University”

Sheridan suggests that "unless we guard against it, the computer will breed isolation, although you could say that students are already isolated. The cruelest kind of competition, which they now seem to be living, has caused them to isolate themselves from each other. [It prevents them] from helping each other and talking about things that are going on. I think we're going to have to work harder to develop a sense of communal access and responsibility."

Van Dam says, "I don't want classes to disappear, I want them to continue. I just want another mode. I don't want to be forced to choose. I know perfectly well that the classroom can be an artificial setting. For a small percentage of people who are articulate, like to show off, or are genuinely unafraid and enjoy the dialogue, it's a good setting. So what do we do? We try to break it down into discussion groups, smaller sections—but these devices are just devices. I'm suggesting that we add another kind of section, the electronic section, where a person can work to overcome the shyness or the fear of communicating. I'm for creating additional avenues, not eliminating them. I now have infinitely more student contact than before. I am pretty difficult to get hold of, but if you send me an electronic message, I will receive it when I log on. When I finally answer my mail, it could be two in the morning, but I answer my mail." (As if to demonstrate van Dam's point, his computer terminal beeped several times in the course of a couple of hours—students and colleagues sending him electronic messages.)

Mary Lewis agrees. "I've had students say, 'I tried to reach you for so long,' when they needed help. If that student could reach me through electronic mail, we wouldn't miss each other. The computer reduces the physical gaps this way."

The announcement that $50 million was going to be spent over the next six years to equip everyone on campus with workstations was greeted with surprise and concern. The administration firmly stressed that this money will be raised from sources other than current operating expenses, and that fund-raising for all other needs will continue.

("There are times when money is available for some things and not for others," explains Shipp. "There isn't any real answer to that. As a University we have to take advantage of the opportunities." Shipp points to the rapidity of fund-raising for the experiment so far: "We've never had a period where in January a group of people started a fund-raising activity and three to four months later there was $15 million in the coffers.")

Among those expressing concern is John Savage, a professor of computer science, who asks, "How do you balance the risk against the opportunity?" A computer scientist who believes the computer is not a panacea, Savage already has access to tools that are more powerful than what will be generally available to the Brown community. "I know what to expect. I'm also aware of work being done in other universities, and I think I have a fairly honest assessment of the potential out there.

"Let me say that this project has the potential to transform the University, hopefully in ways acceptable to all. But it comes at a time when we are pulling out of what most people consider a financial crisis. We are only marginally solvent. We have one building that hasn't been paid for [the geo-chem building], we haven't brought faculty salaries to a level people would find generous, and our library needs a vast infusion of capital. We have had faculty pleading for years to increase the [library] acquisition budget. I know there are faculty on campus housed under inferior conditions. Other faculty members will point to the woefully inadequate classroom situation that needs to be dealt with; students will ask why the financial-aid budget is still lacking. The president is taking a hard position about not putting up internal money for this project," Savage continues. "He can't hold that line indefinitely, simply because for campus computerization to work, it means computers must be in every office. You need a lot of central and distributed resources, and those have to be paid for by somebody. If a faculty member receives a workstation for research, there is no question that he or she will see its potential for teaching. There will then be a demand created for that. The Institute for Research in Information and Scholarship [see below] will bring in machines, but I don't believe they see it as their mission to fund all the computerization that's going to take place on campus. Instead, they will expect departments and administrative offices to raise their own funds. At that point you can't hold the line anymore. You have to pay for these resources out of existing funds."

What Savage has articulated is what van Dam calls the "camel's nose problem." It's an ancient Arab proverb. Once the camel gets his nose into the tent, the rest of the camel will follow soon. "I know what we can't say is, 'Let's put 10,000 workstations all over Brown and by eliminating financial aid, the library, salary raises, let's kill off the University.' We may have won the battle, but we would have lost the war. We are keenly aware that we have to do this primarily with monies we've raised. That's the key issue. But how can we raise those monies? Not by being number five. You have to be number one, you have to be a pioneer. You have to make people willing to invest in you because they think you may conceivably lead to some questions and answers that matter. The money will come if we do good work. Not all of it, there will be some hardships, there will be some reallocations. But it's not something someone is going to decide in lonely splendor. It will be argued fiercely up and down the corridors of power, with all the input and insights of whatever committee is looking at it."

One of the things that makes the Brown experiment different from other projects is the Institute for Research in Information and Scholarship (IRIS), established with support from IBM (see sidebar). "The Institute is really the cornerstone of Brown's entire project," President Howard Swearer said when he announced the establishment of the institute. "From IRIS will stem the technical and creative impulses that will drive and focus a broad range of experiments. Information developed by IRIS will show us how the next generation of computing can best serve faculty and students in the humanities as well as in the sciences, preserving our strong liberal arts tradition."

Shipp has been appointed director of IRIS, and he explains that "there will be an executive committee composed of faculty and staff who will function like a corporate executive committee. This group will be intimately involved in recommending policies, in looking at the directions of the institute's activities." Another committee, made up of project leaders, will be the management committee; another will be responsible for implications and evaluations, and will be looking at social and psychological impacts of the project as well as evaluating education, scholarship, and social changes. Yet another committee will be responsible for training and deployment. "The whole training issue is crucial. In January 1984 there may be hundreds of students with machines that they have bought. Within the next year there could be thousands of these machines on campus, and it's going to be a major effort to provide a whole new kind of training to faculty, staff, and students. One of the biggest problems we saw in talking to the departments is lack of training. We don't have any training facilities for faculty and staff. We're actually sending people to Johnson and Wales College to take courses about computing, which is insane."

"We are trying to distribute the most appropriate technology to the groups on campus that can best benefit."

The question of "who gets what, when" is, according to Shipp, a complicated one that won't be entirely up to IRIS to determine. "There are certain considerations that have to be made primarily on a technical basis," he explains. "For instance, in 1984–85, the workstations have to be used primarily to set up two workstation labs. Those will not be generally available terminal centers, but will be available to courses that use them. So there's a decision that will be made first of all to meet the requirements of the experiment going on and the development process. "We will be requesting applications for uses for the Lisas we have received. The initial hundred IBM PCs are more or less targeted at the biological or physical sciences, while the Lisas are more or less for the arts and social sciences. That has to do partly with the wishes of the manufacturer, and it's a general strategy. The whole name of the game is workstation networks. We want to establish smaller workstation networks within the departments. There will have to be some group formed that will decide and evaluate the proposals for the machines. This is not just a computer science or engineering project. This is a University project. We are trying to distribute the most appropriate technology to the groups on campus that can best benefit. It will be a complicated process."

The industry tie-in is something that raises other intriguing questions. Joan Richards, an assistant professor of history who served on an ad hoc subcommittee of the Faculty Policy Group set up to study the project over the summer, says that one of the committee's concerns is the copyright problems of the software that faculty members will be helping to develop: Who will get the money? Mary Lewis adds, "We in the academic world have been living in a state of innocence. We haven't dealt with the secrecy and the potential for profit that goes on in the business world. The possibilities for us to make money developing the software is looming ahead and we have to start thinking about that. People in the humanities aren't used to being in that position."

"We have to pay attention as best we can to the unanticipated consequences," says Edward Beiser, professor of political science and director of the Center for Law and Liberal Education. "What is an example of an unanticipated consequence? Question: What are the implications of this program for admission decisions at Brown? If we have the potential to give every student at Brown a terminal, should we not when we admit a class try to attract and recruit students who have the capacity to use that terminal? You don't invest in this kind of hardware and then remain indifferent as to whether and how it will be utilized. "By way of analogy, if we accepted the donation of a new language laboratory, so that there was a seat in the lab for every student at Brown, that would make no sense unless lots and lots of students were going to study foreign languages."

Will the project change the kind of student attracted to Brown? Two replies: Dean of the College Harriet Sheridan: "I think if we weren't to do it, it might. The liveliest, most enterprising students that we see at Brown struggling to get into CS11 are coming from all fields. Why shouldn't humanists know about machines? The problem with humanists in the past has been that they haven't wanted to recognize their dependence on machines. Yet they drive cars, use refrigerators and stereos. I would say were we not to do this, we would lose many of the students that we want." Music professor Mary Lewis: "I asked one of my students—one of those who is most wonderful—if he would have come to Brown with these computers. He said he wouldn't, but that students coming in now wouldn't be bothered in the least by this experiment. That's how fast things have changed."

"This institution is special," says Savage. "It has been for a long time a friendly, homey, easy-going place, but we have been experiencing a diminishing sense of community. I would want to know what's causing the change. What disturbs me is that there is no dialogue. We're introducing technology instead of giving attention to the problems people have."

"Are we as a University discussing education enough so that we are ready to discuss this kind of education in conjunction with everything else?" Beiser inquires. "If every professor has a terminal in his office, and terminals are accessible to every student, we will then have a discussion of whether we should have a computer requirement at Brown. But we don't now have real discussions about whether we should have a writing requirement or what that might mean. Or a reading requirement and what that might mean. What is the educational framework within which we will discuss the place of the computer at Brown? The computer issue forces us to interact on some educational issues."

"Brown is attempting to humanize a technological trend," as Lewis puts it. "We have to find ways to use the things creatively. We live in a technological society and we can't run from it."

According to Shipp: "Very little has actually happened yet. The perception is that 'they' have gone so far that all of the decisions have been made. What we've been trying to do is create a set of opportunities. What has complicated things is the success of the fundraising. If it had taken us ten years to raise the initial money, people would have forgotten all about it."

People have not forgotten. The computers are coming and the debate is here. And Brown, ten years from now, will be a vastly different University. The wave that Andy van Dam says we are riding will wash us right into the twenty-first century.