The milk you put in your granola this morning could have come from a myriad of sources: perhaps it was soy milk, or calcium-enriched Lactaid, or organic milk fortified with omega-3 fatty acids. And even if it came from your local dairy, writes Joe Dobrow ’85 in his new book about the health food industry, “local” likely means several hundred miles away. “Your grandparents’ milk? It likely came from the milkman,” Dobrow points out. “Or from the cow.”

The book is packed with funny anecdotes about the quirky characters who collectively built today’s natural-foods juggernaut, usually through dumb luck, outsized hubris, or both. Dobrow begins with the iconoclastic health nut J.I. Rodale, who launched Organic Gardening magazine in 1942, seeding a large publishing empire that even includes the publisher of Dobrow’s book.

He traces a path from macrobiotic pioneers Michio and Aveline Kushi (founders of Erewhon) to Mo Siegel, whose foraging led to Celestial Seasonings teas, and Gary Hirshberg (husband of Meg Hirshberg ’78), whose early years as cofounder of Stonyfield Farms involved “milking cows in the morning” and then driving around town with a cooler bin to deliver the milk. “We just drove fast,” Hirshberg told Dobrow. “Who could afford refrigeration?”

Dobrow tells the story of a retired Los Angeles teacher, Sandy Gooch, who in 1977 founded Mrs. Gooch’s health food supermarkets. The California chain was the first to establish “natural” standards and eventually wielded such buying power that, before manufacturing a product, companies confirmed that a product was “Goochable.” Just fifteen years later, aided by a Harvard MBA and capital from Goldman Sachs, Mark Ordan established Fresh Fields in Maryland. By 2001, however, Texas-based Whole Foods had bought both Fresh Fields and Mrs. Gooch’s, as well as New England’s Bread & Circus and other natural-foods grocery chains across the country, forming a daunting retail behemoth.

Dobrow observes that most of the food brands born of hippie idealism have since been subsumed by megacorporations. Cascadian Farms, for instance, is now owned by General Mills, and Coca-Cola owns Odwalla. “It was,” Dobrow writes, “an ineluctable journey from co-op to co-optation.” He grapples with the contradictions inherent in Corporate Organic, but ultimately concludes that getting natural foods onto our tables is the important part—and if big business helps, then we’ve made “tremendous progress.”

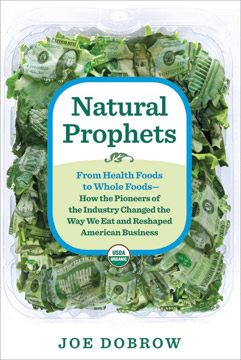

In the end, Natural Prophets adds up to a lively historical mosaic, one that answers the “sort of open-ended rhetorical joke that often went around the co-ops … in the earliest days of the natural-foods revolution,” Dobrow writes: “What happens if the mission actually succeeds?”