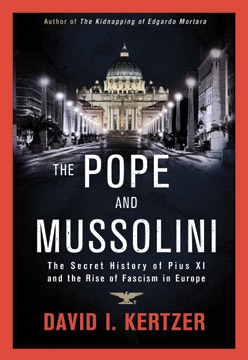

To re-search his new book, The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe,

David I. Kertzer ’69—the Paul Dupee Jr. University Professor of Social

Science and former Brown provost—combed the Vatican Archives and the

records of Il Duce’s secret police. What Kertzer revealed is the story

of a pope who recognized the evil of Fascism too late and was

undermined by others in the Vatican. The Pope and Mussolini, which was edited by David Ebershoff ’91, is the recipient of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for biography.

DK Well, the papacy is a vestige of medieval times that still exists in the West—the notion of a divine ruler—who rules by divine right until death. And there are now 1.2 billion Catholics, so the influence of the pope is enormous. Also, the Vatican sees itself as a political actor on the international sphere.

BAM You begin your book with Pius XI on his deathbed, having collaborated with Mussolini and now too weak to deliver a speech denouncing racism. How do you see Pius XI?

DK I see him as a tragic figure. He was the product of an anti-modernist, medieval mind-set, and, as I see it, this is what causes him to make his deal with fascism. Subsequently, in dealing with Nazism and Mussolini’s embrace of Hitler, Pius XI felt the ideals that had served him so well in the past were not the guide he needed with respect to modern threats and ideologies.

BAM Pius XI called on a Rhode Island Jesuit, John LaFarge, S.J., to draft an encyclical on the evil of racism. The pope died before he could announce it. What happened to it?

DK What I discovered is that Mussolini called on Cardinal Pacelli [who would become Pius XII] to destroy the speech and the encyclical.

BAM How did Mussolini know so much?

DK We know about all the infighting and scandals during this period because there was a thick network of fascist spies in the Vatican during the twenties and especially the thirties. The reports of these informants would go to the head of the police—some through his mistress—and he would report the juiciest bits to Mussolini every morning.

BAM What kinds of juicy tidbits?

DK This is one of the most controversial parts of my book. I will give just one example. The informant reports, together with other police documents, show that a prelate very close to the pope—a man who would become a prominent cardinal—lured boys to his rooms with liquor and money.

BAM Does the current controversy over NSA spying make you see Mussolini’s spying differently?

DK [Laughs] Clearly this was a highly surveilled society. It’s funny because looking at it from a historian’s point of view that’s a good thing. Morally it’s terrible—but, wow, we know details of what was going on behind the scenes that no one could have gotten without these records.

BAM Did you find any documents in the Vatican Archives that just knocked you back in your chair?

DK Yes, there were. Certainly the document that chronicled the deal, two weeks before [Italy’s] anti-Semitic racial laws were announced, promising that no one in the Church would protest them if Mussolini would give favorable treatment to Catholic Action—the lay Catholic organization. That was a shocking document that was buried in the Vatican Archives and only has come to light with its opening.

BAM Were any records off-limits to you?

DK When the Vatican announced that these files would be opened, I asked that question of the prefect of the Vatican Secret Archives and was told, “No—except for certain sensitive personnel files.” [Laughs] We’ll have to go to the secret police files for those records.