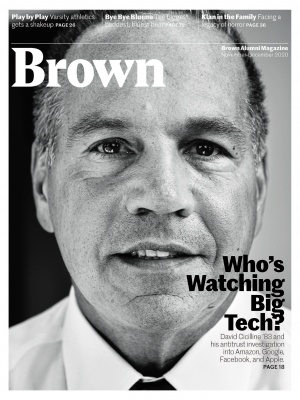

Going Up Against Goliath

He took on Providence Mayor Buddy Cianci and R.I. political corruption. Now he’s coming for Zuckerberg. The unlikely moral crusade of David Cicilline ’83

He may have emerged from the smallest state in the Union, but Rhode Island Congressman David Cicilline ’83 has been confronting giants since his first days in politics. From helping pull up the roots of Rhode Island’s infamous patronage system as a state representative to going up against notorious Providence Mayor Buddy Cianci, Cicilline has a track record of taking on entrenched systems of power—and winning.

This year finds him facing off against four of the most influential leaders in the tech industry—Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Apple—following a year-long Congressional antitrust investigation. The resulting 449-page report, released in October, accuses the companies of

becoming “the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons.”

Cicilline made his views clear when he tore into the companies’ executives at a July hearing on Capitol Hill, asking Google’s CEO Sundra Pichai: “Why does Google steal content from honest businesses?” Pichai deflected the question, only to have Cicilline retort with evidence that Google privileged its own products in search rankings, stifling small businesses on the web. “Our documents show that Google evolved from a turnstile to the rest of the web to a walled garden that increasingly keeps users within its sites,” Cicilline declared.

By the time he reached Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Cicilline—who this fall launched a bid for assistant Speaker of the House—was in his element. He shared testimony from a small business that said Amazon was “the only game in town” and would string companies along into ruin. The small business described Amazon’s platform as heroin for small businesses—addictive and destructive.

“Mr. Bezos, this is one of your partners,” Cicilline asked. “Why on earth would they compare you to a drug dealer?”

Dining with dons

Power, politics, and corruption were all literally at the kitchen table as Cicilline was growing up—members of the Rhode Island mafia would sometimes stop by for dinner. Cicilline’s father, Jack, made his career as a top defense attorney by representing the Patriarca crime family and had a close relationship with his mafioso clients outside the office. He was even the godfather of a mob lieutenant’s daughter.

Yet Cicilline, who adopted his mother’s Jewish faith, says his Catholic father was more than just a mob lawyer; the elder Cicilline also spent many years as a top aide to the mayor of Providence, inspiring his son to become civically involved from a young age. Growing up in Narragansett on Rhode Island’s coast, David would have his mother drive him to town council meetings in his early teens. By the time he reached college, Cicilline was telling people he wanted to be the president of the United States one day.

His longtime friend Bob Walsh ’83 remembers a kid who even in high school was a “tenacious debater,” adamant in defending the hot-button progressive issues of the day, including women’s rights to abortion. In the mock political bodies for students, he was also a leader—elected governor of American Legion Boys State and the speaker of the House for the Rhode Island model legislature.

“If he was a dog catcher, he would catch more dogs than everyone else. That’s just how he is wired,” Walsh says. “He’s a whirlwind of work and always has been.”

Cicilline transferred to Brown as a sophomore from William & Mary, paying his way by waiting tables every summer, and on campus he immersed himself in political science, both in theory and practice. He helped band together John F. Kennedy Jr. ’83 and William Mondale ’85—who came from prominent political families practically at war with each other in the Democratic party—into Brown’s new chapter of College Democrats.

Walsh recalls that when they volunteered on campaigns for local politicians, Cicilline always made himself available for the grunt work even as a full-time student, often fielding calls in the pre-dawn hours for his bosses. He learned campaigning the old fashioned way, heading to City Hall with a highlighter and photocopies of voter rolls while he took classes on the logistics of campaigns and elections, learning the importance of skills like cross-tabulation and polling. A former professor, Darrell West, recalls that Cicilline would bring a big box of pastries for the political science faculty on holidays. “The constituent service was very strong, even then,” West says.

Cicilline went to Georgetown for law, then served as a public defender for a couple of years before moving into a more lucrative private practice that allowed him to indulge his taste for stylish cars: he owned, at one point, a Rolls Royce and a Jaguar. (Later in his political career he would cruise the streets of Providence on a Harley and ride a horse he affectionately called “Capitol Hill.”) But despite his affluence, he still made time to represent clients for the ACLU and took a special interest in combating police brutality and misconduct.

In the early ’90s, as he prepared to enter politics for the first time, Cicilline reached out to H. Philip West, Jr., then the director of Common Cause Rhode Island, a nonpartisan organization promoting ethical governance. West recalls that he was skeptical of the ethics of a guy whose father was tied to the mob and he wondered if Cicilline was considering politics to benefit from cronyism.

Instead, soon after being elected in 1994 to represent the affluent East Side of Providence in the state’s House of Representatives, Cicilline became a leading force in an effort to dismantle the system powering the political machine of Rhode Island Democrats. Seeing Cicilline go up against his own party, West came to believe that the representative, an outspoken liberal, would be genuinely committed to reform. That spirit was badly needed in Rhode Island’s legislature, West says, thanks to a culture of corruption stemming from Rhode Island’s uniquely anti-democratic Constitution, which lacked an appropriate separation of powers. The state Constitution allowed lawmakers to create commissions and boards tasked with doling out millions of dollars in contracts, and then appoint the members to those bodies or even serve on them themselves. No other state allowed for this, and Rhode Island’s system proved to be “an engine of patronage,” explains West, whose organization led a campaign to reform the state’s Constitution in the ’90s. “It was beyond absurd, the conflicts of interests,” recalls West, who wrote a book, Secrets & Scandals, about the reform efforts. “But it was deeply rooted; part of the culture. And so to ask to change that was the worst kind of heresy you can imagine.”

When Cicilline was asked if he was concerned about retribution from the Speaker of the House—who warned the reform movement was “a declaration of war”—Cicilline replied: “Maybe I’m a glutton for punishment. But this is both right and long overdue.”

Propelled by the work of Cicilline and a group of other committed legislators, Rhode Island finally succeeded in reforming its Constitution in the early 2000s, removing the special powers of the legislature.

Besting Mayor Buddy

In 2002, Cicilline decided to go for the jugular of Providence’s corruption by running for mayor against incumbent Buddy Cianci—although fate would intervene before the two could go head to head in the elections.

The city’s longest serving mayor, Cianci was a popular presence in Providence bars and restaurants, known for his cigars, garish sense of humor, and disgruntled toupee dubbed “the rug.” He had first served as mayor from ’75 to ’84, but was forced to step down for kidnapping and attacking his ex-wife’s alleged lover with a log and a burning cigarette, and then became a popular talk-show host. Back in the mayor’s office by 1991, the charismatic Cianci, having once run on an anti-corruption platform, proceeded to peddle his own branded marinara sauce while in office (the proceeds, it was later revealed, did not benefit Providence schoolchildren as advertised). By 1998, Cianci had cemented a reputation as a brutal and beloved demagogue, so feared that he ran unopposed for re-election that year.

Circumstances had changed by the 2002 mayoral election, as an FBI probe had for the previous few years been circling closer and closer around Cianci, looking into charges of racketeering and corruption. Still, his would-be challengers hung back, too scared to enter the ring with the undisputed heavyweight champion of Providence politics. No one knew if the feds would find the evidence needed to convict the Don of City Hall. Besides, Cianci’s personality defused the seriousness of the accusations, and a majority of citizens polled at the time said they thought Cianci was doing just fine as mayor.

Nevertheless, alone among Providence politicians, Cicilline chose to announce his candidacy. As Cicilline tells it, he had spent years griping with colleagues and constituents about the corruption of the Cianci administration and decided the timing was right to do something about it.

“It occurred to me that rather than grumble and complain, the only way to take on that kind of corrupt leadership was to run against it,” Cicilline told the BAM.

Months later, after Cianci was indicted and forced out of the race in order to serve five years in federal prison, candidates rushed to announce their campaigns. But Cicilline had made an impression on voters with the courage of his early start and he won the general election in a landslide, becoming the first openly gay mayor of a major U.S. city. Declaring a new era “guided by those old-fashioned principles of right and wrong,” Cicilline took up residency in an office where the smell of Cianci’s trademark cigars still lingered on the furnishings, and, over eight years as mayor, set about the task of instilling ethics into the city’s administration. Cicilline himself would be marred with a scandal after leaving City Hall for Congress in 2012, when he was lambasted for saying the city was in “excellent financial condition.” In reality, Providence was mired in a $110 million deficit. His approvals sank and the Providence Journal called him “a dead man walking”—but he hung on and kept his Congressional seat. Voters have since largely forgiven him, focusing on his progressive policies, chutzpah, and love of mingling with constituents. Those who know him say he has a joy for the events most politicians grow tired of: the mixers at senior homes, residential picnics, and other small and unglamorous gatherings and conversations that show a representative cares about connecting with the community.

Cicilline has a joy for the events most politicians grow tired of: the mixers at senior homes, residential picnics, and other small and unglamorous gatherings and conversations.

Perhaps another reason for Cicilline’s enduring success—since getting into office in 1994, he’s never lost an election—is that he appears, overall, to genuinely stick by his principles, even in the little moments. His friend Bob Walsh recalls that after Cicilline became mayor, he walked out of the transition headquarters to find a city official writing a ticket for his car. The official realized whose car it was and apologized, explaining the ticket would be “taken care of.”

“No you won’t,” said Cicilline, saying he would pay the fine. “That’s exactly why I ran.”

Bigger fish

Cicilline was sworn into Congress in 2011, and in the nine years since he has established a record fighting to stop proposed cuts to Medicare and Social Security and pushing for gun control legislation, including authoring a bill to ban assault weapons (he once joined John Lewis in a sit-in on the House floor in 2016 to protest the lack of gun control reforms). He’s also introduced legislation to automatically register voters at the DMV and to extend anti-discrimination protections to the LGBT community by expanding the definition of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

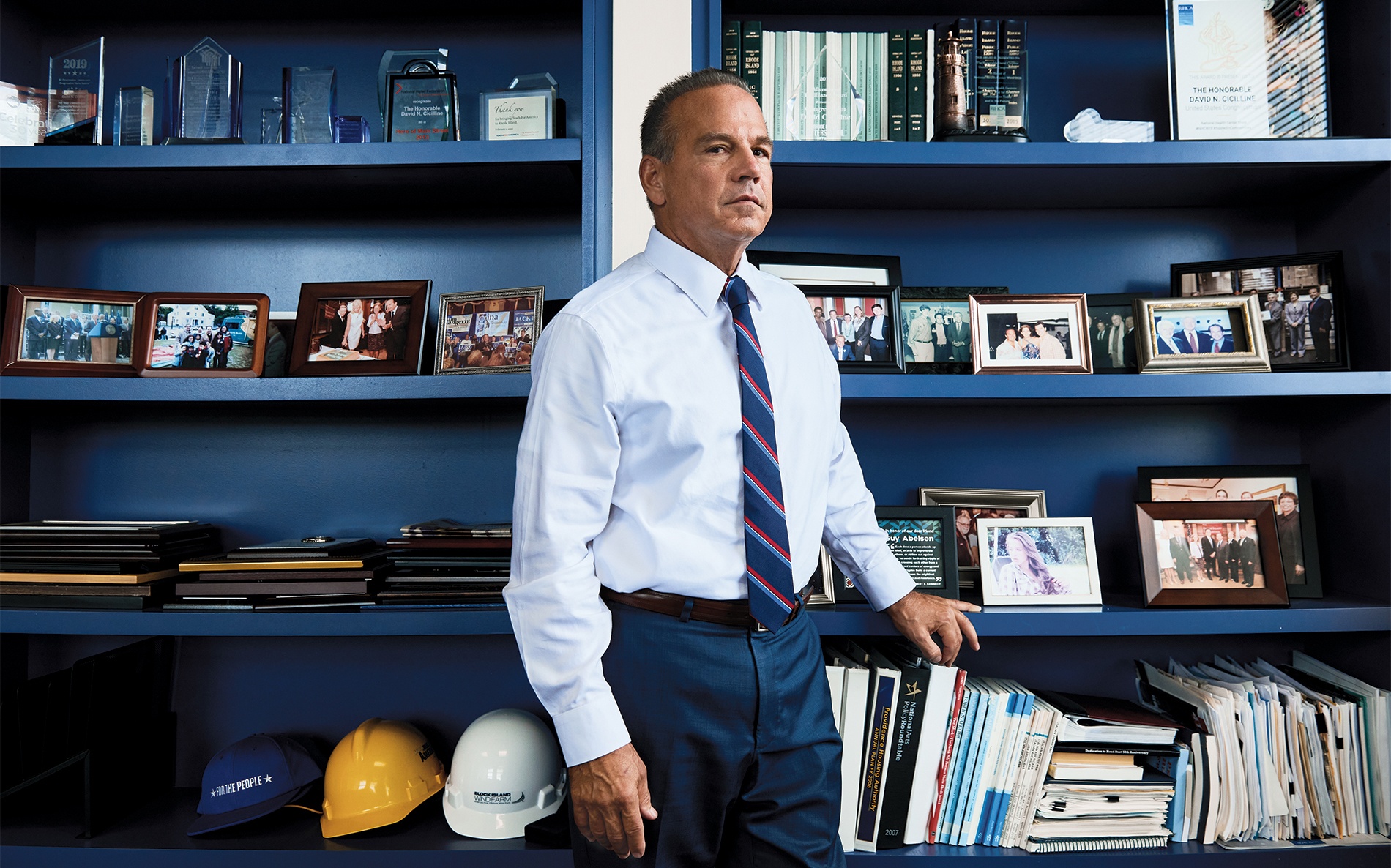

Now, as chair of the House Judiciary’s subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law, he’s uniquely well-positioned to go into battle against the likes of Mark Zuckerberg and Big Tech. Cicilline has been vocal about how he believes these companies are harming Americans and the market itself.

“Simply put, they have too much power,” Cicilline declared in his opening statement at the hearing on July 29th. “This power staves off new forms of competition, creativity, and innovation....Their dominance is killing the small businesses, manufacturing, and overall dynamism that are the engines of the American economy.”

Cicilline has led a dogged effort to gather the evidence necessary to make the case to the American public that Congress should intervene in reshaping the digital economy—at a time when many Americans are increasingly wary of how Big Tech companies dominate everyday life and online infrastructure. After reviewing more than a million documents and interviewing hundreds of business owners and tech industry players, Cicilline’s report concludes that the four companies—worth nearly $5 trillion combined—are “unaccountable to anyone but themselves.”

“Our responsibility is to make sure there is real competition and that the monopoly power of these large technology platforms is checked,” Cicilline tells the BAM. “We know the consequences of this concentrated economic power—it very often creates concentrated political power, which is really inconsistent with democracy.”

Not that Mark Zuckerberg plans to let his company get dismantled without a fight. At the July hearing, he made the case that Facebook and other Big Tech companies were benefiting consumers by innovating within a competitive marketplace.

“We’re here to talk about online platforms, but I think the true nature of competition is much broader,” Zuckerberg said. “When Facebook bought WhatsApp, we could compete against [telephone companies] that used to charge twenty-five cents a text message, but not anymore. Now people can...send private messages for free. That’s competition.”

Zuckerberg was expressing a now-dominant theory of American antitrust law: that these issues should be evaluated by the prices people have to pay for goods and services. So long as things are cheaper than before, everything is all right.

Monopoly philosophy

Originally, antitrust law focused on breaking up the classic monopolies like John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which dominated markets at the expense of a more diverse range of smaller companies. The bedrock of antitrust law, created in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was premised on the notion that the fewer companies operating in a market, the more likely there will be anti-competitive practices.

But for decades, that view has been mostly out of fashion. The current consensus on antitrust issues took off after conservative legal scholar Robert Bork’s seminal 1978 book, The Antitrust Paradox. Bork argued that antitrust law should be primarily concerned with protecting consumers, not competitors. Mergers and market integration should be welcomed because they make things more efficient, leading to lower consumer prices.

Yet there has been an increasingly vocal group of economists, legal theorists, and legislators, Cicilline among them, that has argued that to truly assess competition in today’s economy, a broader and more nuanced approach is needed. Leading the charge is wunderkind scholar Lina Khan who, while still in her 20s, wrote a groundbreaking paper published in 2017 that analyzed the dangers of Amazon’s rise by drawing on traditional but out of favor concepts of antitrust law. Price and quality of product alone are not enough to judge the competitiveness of markets, she says. We need a broader, more holistic view, since the structure of companies like Amazon and Google has increasingly become the structure of the marketplace.

As a result, the question that we should be asking in antitrust law, Khan says, is whether a company’s structure creates “anticompetitive conflicts of interests” across a range of markets, allowing harmful, predatory practices to persist. Cicilline hired Khan as an advisor, and his committee’s report highlights how each company consolidated its power by exploiting one-sided access to data and control over distribution, allowing them “to acquire, copy, or kill” competitors. The impact of this consolidation may not be reflected in higher prices for goods and services but may harm consumers and the market in less tangible, more insidious ways such as violation of user privacy, the decline of accurate information, and the undermining of democratic processes.

Facebook’s acquisitions of What’s App and Instagram appear to have led to more competition between its own products than with actual rivals, according to the company’s own estimations. And businesses in peripheral markets, such as local newspapers, have collapsed in part due to the rise of Facebook. The lack of competition allows for proliferation of disinformation on the platform, Cicilline argues. The company notoriously offers a seemingly free service that profits off its users’ personal data, sold to shadowy firms like Cambridge Analytica—now well known as having attempted, perhaps successfully, to influence the 2016 election. Meanwhile, more than a third of Amazon’s 2.3 million third-party sellers rely on the platform as their only source of income, and any developer releasing a product on Apple’s app store has to fork over 30 percent of their revenue.

As the report explains, by running the market and competing in it at the same time, these companies are able “to write one set of rules for others, while they play by another.”

In other words, as Cicilline’s report explains, by running the market and competing in it at the same time, these companies are able “to write one set of rules for others, while they play by another.” And the report found that these companies are often unscrupulous in the ways they maintain their grip on the market. Google, for instance, is effectively the only search engine in town, bolstering its own products in searches, downgrading those of competitors, and “extorting” companies that want to get seen by users.

While the practices sound sketchy, clearly proving harm to consumers and the marketplace as a whole is not an easy task, notes Darrell West, the former director of Brown’s Taubman Center for Public Policy. West believes his former student is taking the right steps to build the consensus to crack down on Big Tech.

“You need evidence of actual wrongdoing,” explains Darrell West, now a senior fellow at Brookings. “David has spent the last year really developing the evidence, setting the agenda. It’s not enough to just say the tech companies have acted badly—you need to have concrete illustrations.”

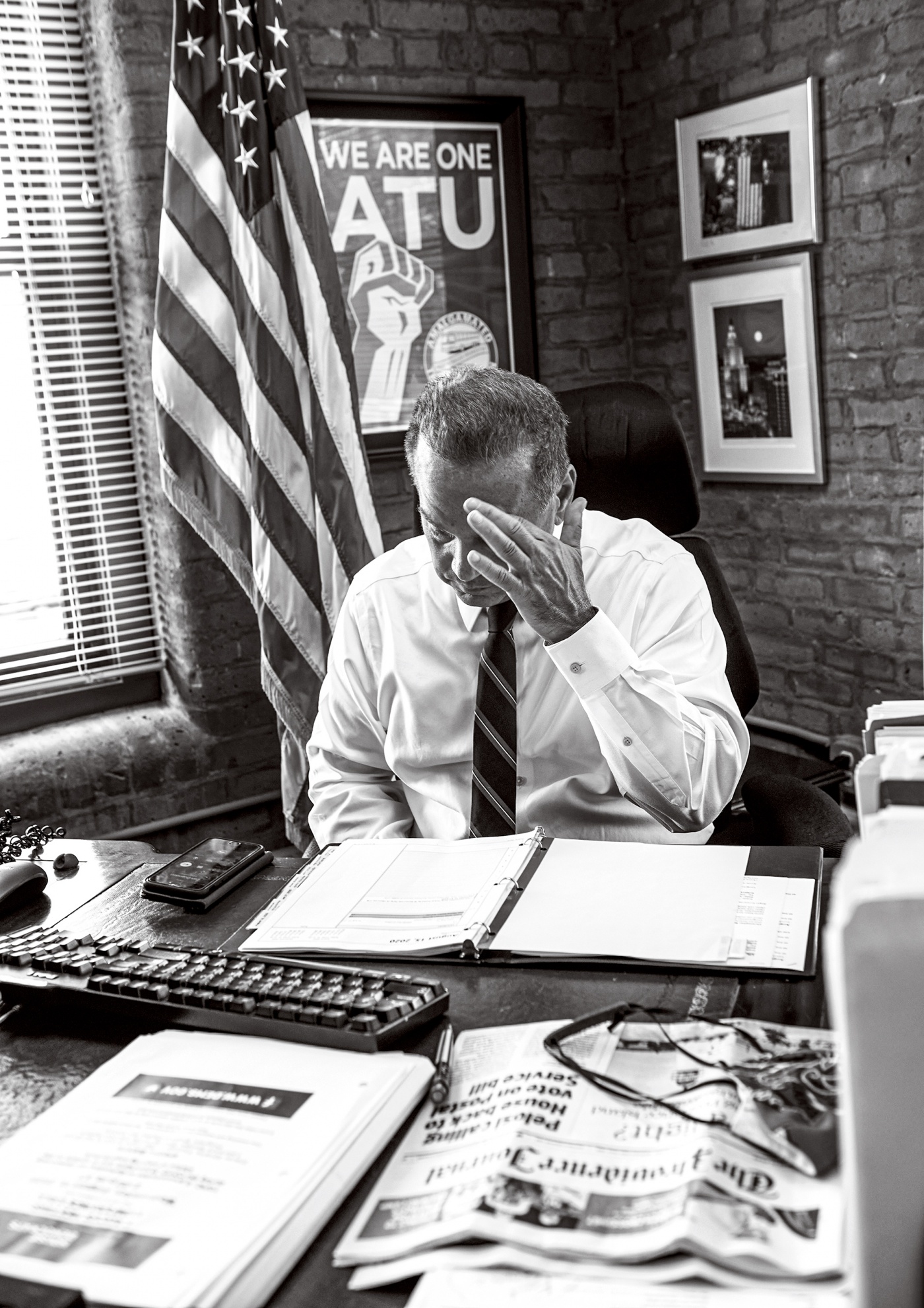

Cicilline has always thrived on the theatrics of the public forum and he made forceful points at the hearings. The real question is whether his rhetorical grillings—and the subsequent report and its findings—will translate into substantive Congressional policy.

Cicilline points out that this is the first major Congressional antitrust investigation in decades, and that his committee’s report offers a menu of policy options for better regulating the digital economy. Along with increasing scrutiny over mergers, the report notably calls for the companies to be broken up and barred from operating across adjacent lines of business. Cicilline’s Republican colleagues felt the report went too far and disavowed its conclusions. But Cicilline believes major intervention is needed.

“I think it’s pretty clear from our investigation that these large platforms really have monopoly power,” he says. He argues that Facebook, in particular, should not have been allowed to acquire WhatsApp and Instagram. Even so, “there is certainly an ability under existing law to go back and unwind that transaction,” Cicilline adds.

Whether that’s feasible remains to be seen—but if anyone could break up Big Tech, Walsh believes it is Cicilline, who seems never to have lost the idealistic spirit of those early campus campaigns. “We were all running around trying to change the world,” Walsh says. “David still believes we can.”

Jack Brook ’19 is a 2020-2021 Luce Scholar and received the 2019 Betsy Amanda Lehman ’77 Award for Excellence in Journalism.