Storytelling through Song

In music theory class, students learn classical rules— and how to break them.

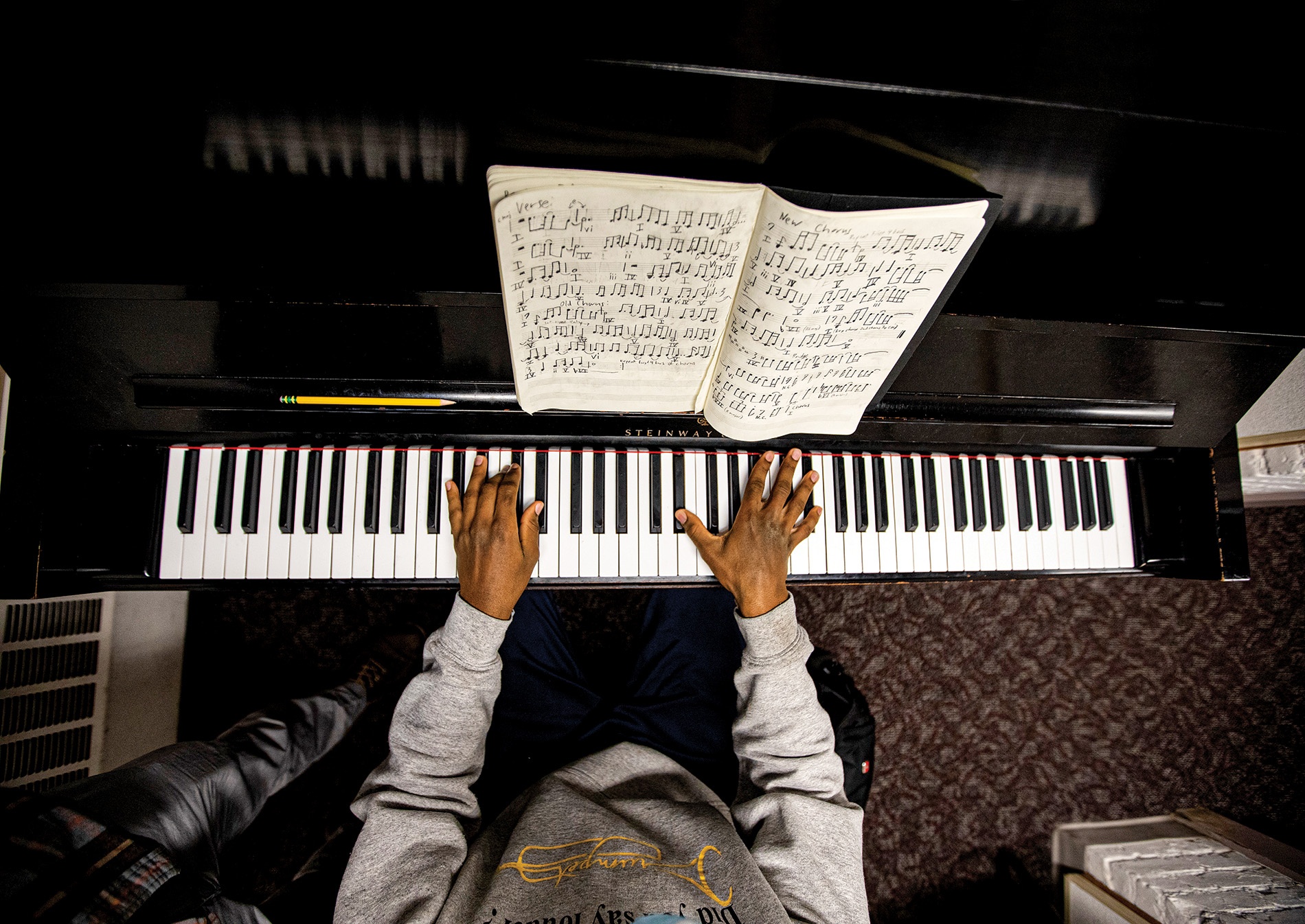

Derrick Pennix ’25 loves telling stories. As a high school student in Granger, Indiana, he created and published a five-part stop-motion animated series. Pennix aspires to a career that involves storytelling—so his first semester he enrolled in Theory of Tonal Music I, taught by Associate Professor of Music and composer Eric Nathan, to learn how to tell a story through music. Throughout the semester, he and his classmates engaged in intensive study of music’s building blocks. By analyzing music composed by artists from Johann Sebastian Bach to Billie Eilish, they learned how certain chords can communicate particular emotions, how chord progressions can build and release tension, and how words, rhythms, and notes work together to set a scene.

“You can analyze a piece of music in a similar way to how literature students might analyze a poem,” says Nathan, who has taught the course many times over the last six years. “You can pick apart individual chords and passages, study their meaning, compare them to similar chords and passages written by other musicians.”

On Tuesday, Dec. 7, Pennix shared a sketch of his untitled pop song with Nathan and classmates in Grant Recital Hall. He says he began the songwriting process—which took more than a month—with the big, sweeping, culminating chorus. “If you know how you want the story to end,” Pennix says, “it helps you think about the journey you’ll have to take to get there.”

From Bach to the Beatles

Just as literature students have often turned to William Shakespeare or Jane Austen for guidance on how to craft a traditional story arc, Nathan says, music theory courses have typically begun with the analysis of 17th- and 18th-century music by European composers such as Bach and Mozart, whose influence can still be heard in most Western popular music. (In fact, a famous chord series dubbed the “two-five-one progression” can be heard in everything from Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos to the jazz standard “Satin Doll” to the Beatles’ “If I Fell.”)

“Some of the concepts introduced by these European composers are still applicable to music we hear today—like the concept of dissonance and resolution, where there’s a sense of tension that’s then released,” Nathan says. “But some popular music breaks from tradition, and when it does, it can subvert expectations in a wonderful way.”

That’s why, in Nathan’s theory class, students also learn how to analyze contemporary popular music. In early October, he asked students to break down the chord progressions in Olivia Rodrigo’s recent hit “Driver’s License.” Two weeks later, students were analyzing chord structures in an aria by Hortense de Beauharnais, a French queen consort who was writing music at the same time as Ludwig van Beethoven and Joseph Haydn.

“This is somewhat of an introductory course, but it’s also very rigorous: There’s a lab component that requires keyboard skills, singing, and ear training,” Nathan says. “It’s also a place where you have to explore those concepts on your own, on an empty page.”

Nathan says he wanted to challenge students to write a pop song so they felt freedom to employ or disregard musical conventions as they saw fit—something they may have felt less free to do with a classical composition.

“I think it’s important to use the knowledge you’ve gained to compose in a different way,” he explains. “Much of the original music out there works within a particular tradition but adds just enough of a unique voice and a unique world to set it apart. I think it’s fun to ask students to balance the conventional and the new the same way today’s pop artists do.”

Pennix agrees. As he built his melody, he found ways to subtly subvert expectations. Most songs start with lower notes, he explains, and build upward toward an exciting chorus. He decided his verses would start with a high note. And to build tension before the chorus, he introduced a tritone—a musical interval that sounds unsettling and brash. “I think it’s really helpful to know the basics, because once you have those down, you can start to break the rules,” he said.

Composition as empowerment

Nathan says it’s safe to assume that most college students who take intensive music theory courses such as these are aspiring professional musicians. But at Brown, the dozens of students enrolled this fall represent a diverse array of backgrounds.

Some who come from outside the music concentration, such as computer science concentrator Kshitij Sachan ’22, were once embedded in the world of music. In high school, Sachan says, he had seriously considered attending a music conservatory for flute performance. Instead, he chose to attend Brown, where the Open Curriculum afforded him the opportunity to explore a wide range of interests—including music.

Sachan says that a semester of analyzing music and composing his own song has opened his eyes to concepts he only hazily understood as a younger musician. “I organized a pop band in high school with my friends, and now I laugh at how little we knew when trying to arrange pieces,” Sachan says. “Now I can do mini jam sessions with my housemates and understand what’s going on behind the scenes musically.”

Sachan says he was still tinkering with his song, even days after turning it in to Nathan. He was working with roommates to add percussion and lyrics in GarageBand. He realized that the course hadn’t just taught him how to write a song but also empowered him to become a musician again. “It felt like the only way I could be involved in music was to get really good at flute, and if I couldn’t do that, then there was no space for music in my life,” he says. Sachan is now considering joining an amateur orchestra when he graduates.

Pennix, who had some childhood experience on the trumpet, says he was grateful that Nathan began the semester with a review of chords, scales, and intervals—and that the rest of the semester challenged him to understand the intricacies of emotion in music. “The more I can understand music, the better writer I can become,” he says. “For me, film, music, and writing all go hand in hand, because what they all have in common is emotion. If I’m able to learn how to create emotion with words, film and music, I can become a better storyteller all around.”