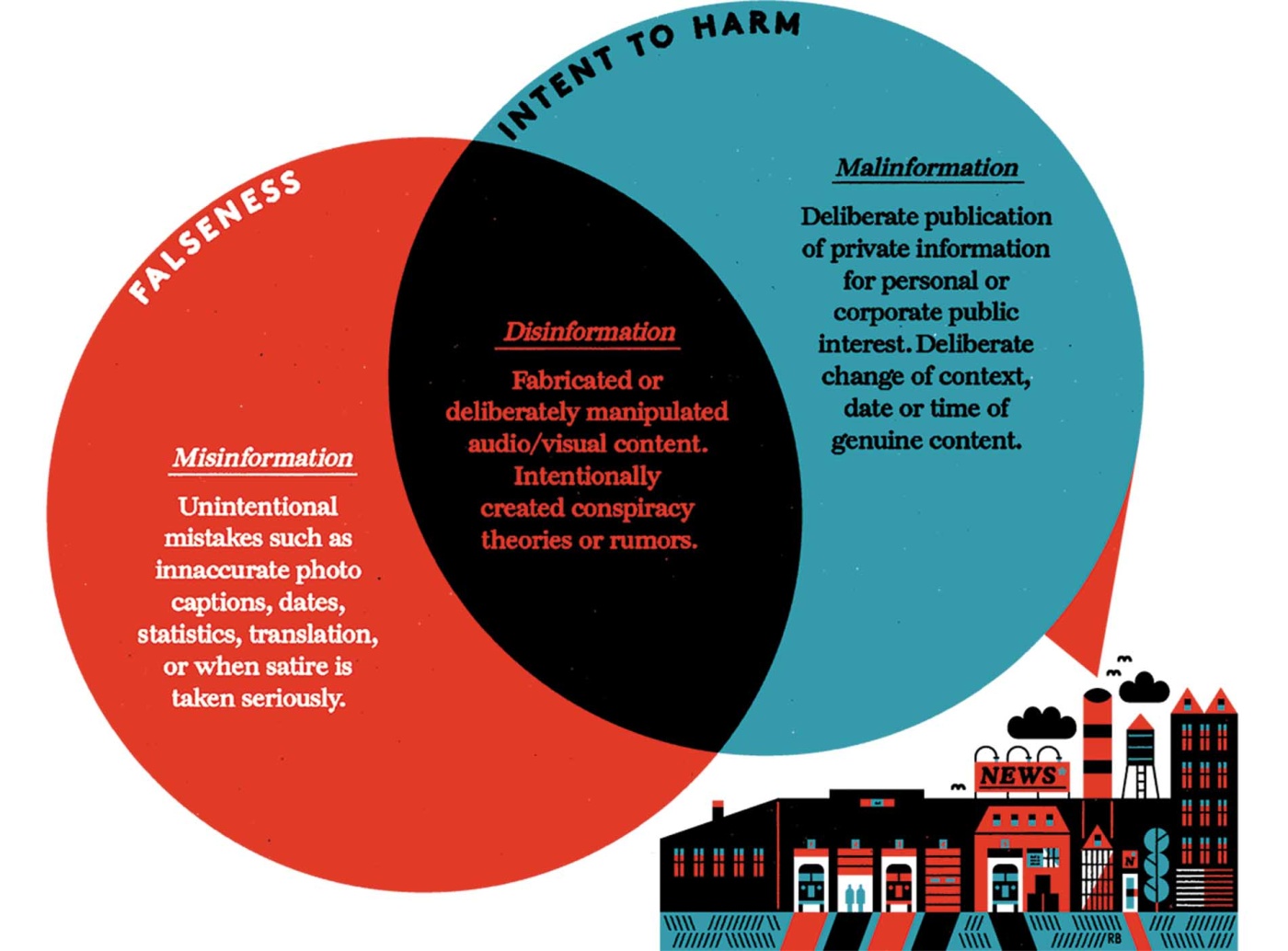

Rx for “Information Disorder”

Disinformation is making us sick, literally. Asking the right questions and training the right people may be the cure.

Brown’s School of Public Health may seem an odd home for a lab fighting disinformation. But newly hired Professor of the Practice Claire Wardle insists otherwise. “Americans think of information disorder largely as a political problem,” Wardle says, “but globally, health and science have always been the biggest victims.” Rampant disinformation surrounds HIV, Ebola, and cancer cures. “The pandemic really shone a light on this and got people to understand that quality of information really is a social determiner of your health,” Wardle adds. “Do you drink? Do you smoke? Where do you get your news?”

Since 2009, Wardle has been in the vanguard battling what she calls “information disorder.” She pioneered the field of video content verification, creating veracity training for the BBC, which was widely adopted. A decade ago, there were no guidelines for ensuring video—especially user-generated video—was what it was said to be. Was the footage of the carousel in the Hudson River really from Hurricane Sandy? Yep. Were certain colossal storm vids purported to be Sandy real? Not even close. Wardle went on to head news at the social media intel agency Storyful and ran social media at the United Nations Human Rights Council. In 2015 she cofounded First Draft, a scrappy nonprofit and major force in training newsrooms worldwide on verification, as well as in identifying and blunting false news stories, often in election cycles, before they can go viral.

Wardle joined SPH in late 2021, set on tapping Brown’s multidisciplinary environment. She has long advocated a collaborative response: The bad guys don’t limit themselves to media silos or academic communities; they don’t play by any rules. Wardle says the good guys, perennially playing catch-up, have to work together more, and better, to effectively fight back.

With that in mind, she launched Information Futures Lab (IFL) in June to actively connect researchers with each other and speed creation of practical, research-based measures to counter disinformation for front line workers like journalists and healthcare workers. A fellowship program is launching in January, welcoming Mark Scott, Chief Technology Correspondent at Politico, as the program’s first visiting fellow.

The IFL has hosted multiple events so far, including convening experts to hammer out transparency demands and metrics for social networks like Facebook and Twitter, and to build a curriculum to educate students on how they’re being targeted and tracked by social media companies and why they should care: What if, for example, data harvesting leads to being denied health insurance or a mortgage in the future?

The lab has also conducted a six-month review of all research published on misinformation intervention about COVID 19. It yielded few clear answers: The research, she says, is “all over the place, using different methodologies.” The IFL’s recommendations clamor for interdisciplinary collaboration, to foster essential, apples-to-apples comparisons and to speed the response to “the most important problem of our time.”

“The knowledge illusion”

The connection between our health and where we get our information is something Steven Sloman, professor of Cognitive, Linguistic & Psychological Sciences, has gained striking insight on. A 2021 paper he coauthored, “Walking the Party Line,” found that sources of information—and health outcomes—differed widely based on political affiliation.

“Our sense of knowing something often comes from what our community or our trusted sources—friends, colleagues—claim to know,” Sloman says. His research suggests that concentrating on facts to fight bad information may be ineffective, and that there should be at least as much focus on the trustworthiness of the source of information.

In his book The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone, Sloman outlined how research has shown we tend to think we know more than we do. “If we can make people less confident and thus more accurate about how much they know about a particular topic,” he says, “then we might be able to get them to question the information they receive to a greater extent.” Once people understand they don’t know as much as they thought about immigration, say, they may be willing to consider it more critically.

One way to reduce unwarranted hubris: “Simply ask the person to explain how a thing works,” Sloman says. A flush toilet, for example—unless you can explain how a trapway induces siphoning, you don’t know how it works. “They’ll discover they can’t, and that they don’t know as much as they thought they did.” Then, less sure of their knowledge, they might be more willing to question other assumptions.

“The *@#%* media”

Fact-checking is something Jonathan Ebinger ’84 wants the young students attending his Summer@Brown Pre-College course to get used to doing for themselves. A former ABC Nightline producer and longtime instructor at both George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs and Brown, Ebinger brought back his groundbreaking course, The *@#%* Media: Enough Disinformation!, for the 2022 summer session (he first taught the class in 2016, year of fake news).

For many of Ebinger’s students, who come from around the globe, the class is the first time they’ve been encouraged to consider the role of the media critically. This year, Ukraine war news came under the microscope: the challenges Russian journalists faced, what they might be perpetrating working for certain media, what news on the war people were getting depending on where they lived.

But learning to gauge the accuracy of hard news and politics isn’t the only point. “You don’t have to be the next one to call out Trump, or make a claim about the Biden White House,” Ebinger tells his students. In class, he cited Reddit sleuths who discovered that parts of a scene in the season finale of The Kardashians were actually shot in January—six weeks after “reality tv” viewers were told it happened. How? By spotting the two distinctly different manicures Kourtney Kardashian sported in that single meeting—one of which, press showed, she hadn’t gotten till January. (There was suspect dialogue, too, but the nails nailed it.) “Knowledge is good,” he quips.