Family Matters

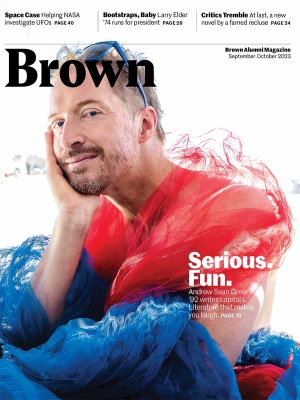

Hard work. Personal responsibility. Republican presidential candidate Larry Elder ’74 aims to re-parent America the way his dad raised him.

Presidential candidate Larry Elder ’74 is prepared to tell you how to raise your kids.

Though Laurence “Larry” Elder has no children of his own—he and his ex-wife ultimately split because she wanted kids and he didn’t—he does not see this as a problem, because his conservative politics were formed largely out of his relationship with his own father. Memories from his youth, calcified by time and experience, serve as the basis for his conclusions on what is missing from the American family and why his ideals are the antidote Americans desperately need.

“The welfare state, in my opinion, has incentivized women to marry the government and has incentivized men to abandon their financial and moral responsibility,” he says. “And you look at virtually every other social problem—whether it’s crime, whether it’s school dropouts, whether it’s people who are not able to compete in the digital age—it all starts from the family. The other things are just symptoms.”

It is upon this position that Elder stakes his bid against Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis in the primaries for the 2024 general election. Though the retired, but still popular, talk show host and onetime candidate for California governor identifies as a “small-L libertarian,” he has no lofty illusions about running as a third party candidate: “Libertarians might get 1 or 2 percent of the vote when they run. But, not unlike Milton Friedman, I’m a registered Republican.”

Indeed, over the past three decades, the former attorney has become one of the most well-known Black Republicans in the country, with a career as the self-styled Sage of South Central built by logging more than 27,000 hours on air and inviting vociferous debate with guests across the political spectrum that has often served to anchor him even more firmly in his opinions.

In the late 1980s, after founding a successful executive search firm, Elder landed an opportunity hosting a TV show on a Cleveland PBS station before pivoting to his own Los Angeles radio show on KABC in the ’90s. Last year, he aired the final episode of the nationally syndicated Larry Elder Show, where Elder says his goal was to inform, provoke, and uplift while hitting on themes of “hard work, accountability, and personal responsibility.”

“The welfare state, in my opinion, has incentivized women to marry the government and men to abandon their financial and moral responsibility... Look at virtually every other social problem—it all starts from the family.”

Elder’s first taste of politics came during the 2021 California gubernatorial recall election, when he took a brief break from radio to emerge as the leading contender against incumbent Gavin Newsom, a liberal whose popularity was waning after he was documented violating his state’s strict COVID lockdowns to meet with lobbyists at a fancy restaurant. While California consistently votes blue, the rules of the recall offered Elder an unusual chance at winning the election, galvanizing California’s conservatives: If the majority of citizens voted to recall Newsom, then the replacement candidate with the most votes would become the new governor—even without a majority.

Newsom won the vote against the recall handily in the end, and Elder has since set his sights on the presidency, gearing up for the campaign more than two years ahead of Election Day and months before making his official announcement in April. Last October, he joined fellow conservative talk show star Sean Hannity for a town hall in Phoenix, followed by his fourth visit to Iowa, because “if you’re serious about running for president, you gotta go to Iowa.”

A professed lover of small government and a devout Christian, Elder’s views are predictably anti-immigration, anti-climate action, anti-abortion (his preferred term for pro-choice is “pro-death”), and anti-anti-racism. His belief that racism “has never been a more minor problem in America” regularly ruffles feathers in and out of the Black community; the Los Angeles Times once dubbed him “the Black face of white supremacy.” But less predictable, perhaps, is the origin story behind these beliefs, a revilement of the single-parent household that might suggest an absentee dad in his own life.

In a certain way this is true—at one point, the two didn’t talk for a decade—but in another, more important way, Elder’s father was deeply present, impressing traditional Republican beliefs into young Elder’s spirit during his most formative years.

“My dad always told us that Democrats want to give you something for nothing,” Elder recalls, “and he went through stuff I can’t even imagine, even being called a nigger in open court.

“Not only did he endure that and come out not bitter and not angry, but my dad believed in America and American values—even though he was obviously aware that America was not living up to those ideals,” he continues. “He worked his ass off, two full-time jobs, cleaning toilets. He cooked for a family on the weekends because he wanted my mom to be a stay-at-home mom, and he went to high school to get his GED. I saw that every single day, and it just made me realize we had to work hard if we’re gonna get anywhere in life.”

Out of step

It was more than 50 years ago when Elder realized, perhaps for the first time, that he was not like his peers, noticeably “out of step with how most Black people think about politics.” The moment came during a high school class when Elder was 15, and heard this poem—which he is still able to recite almost perfectly from memory—for the first time:

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, “Nigger.”

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That’s all that I remember.

—“Incident” by Countee Cullen

Elder’s African-American literature teacher analyzed the poem with rage toward the Baltimorean; Elder mulled over those same lines with irritation toward his teacher. When he went home, he recited the poem for his mother, who replied without skipping a beat, “Larry, what a shame he allowed something like that to spoil his vacation.”

Though he couldn’t have pinpointed its root at the time, Elder thus arrived a freshman at Brown in 1970 with an already ingrained belief that Jim Crow–era racism was no more, and that his fellow Black Americans were being bamboozled by Democrats who “want Black people to be angry and to believe that America remains systemically racist” in order to posture their candidates as heroes and agents of change.

“A lot of Black people have been trained to be angry about stuff that happened to their grandfathers or their great-great-grandfathers, but didn’t happen to them, and I’ve always felt uncomfortable about that,” Elder says.

On a liberal campus, in a political climate still swirling with the assassinations of King and two Kennedys, Elder’s views were an open challenge to the status quo, and one he relished. In and out of class, he clashed with classmates—and one particularly militant Black girlfriend he dated most of his four years—about what was and wasn’t racism, what should and shouldn’t be considered free speech, and what issues did and did not warrant cries for systemic reform.

When Nobel-prize winning physicist William Shockley, who advocated strongly for the theory that Blacks are genetically inferior to whites, was invited to speak at Princeton in 1973, Elder argued long and hard with his then-girlfriend over whether she should get on a bus to Princeton with other Brown students to join in protesting against his visit.

“A lot of Black people have been trained to be angry about stuff that happened to their grandfathers or their great-great-grandfathers, but didn’t happen to them, and I’ve always felt uncomfortable about that.”

“The way to deal with somebody who makes an argument you don’t like is with information, to refute what he says. You don’t shut him down, that’s just wrong,” Elder insisted then, as he still does today. “He has a right to have his point of view, and your job if you don’t agree with it—and I don’t agree with it—is to show why he’s wrong.”

As Elder graduated, migrated—first to Ohio, then California—and stumbled into talk radio, he found no shortage of people with whom to debate and disagree. His brother and mom, a lifelong “John Kennedy Democrat,” were both frequent flyers on the show until it aired its final episode on the Salem Radio Network last year. And while Elder says he never turns down a genuine offer for conversation, he warns any eager young liberals that he’s not so quick to change the opinions he’s allowed to simmer and sharpen for years.

“If you’ve thought things through over a long period of time, the likelihood is you’re gonna be pretty immovable in your views,” he posits. “But I’m open to alternatives.”

Prodigal son

“I have a job at 25 years old making the equivalent of $150,000, and I can’t sleep,” Elder recalls. “And I knew it had to do with my dad.”

It is the late 1970s and Elder is an expensive lawyer in Cleveland, Ohio, living a life that should have been inconceivable to the poor Black boy of South Central Los Angeles, whose high school would later become the subject of the 1991 crime drama Boyz n the Hood. Out of poverty, he has found money and success, yet he is tossing in his bed unhappy because, though not a traditional family man, Elder does care about family.

“I was thinking about my father, not that I thought we’d ever be friends, but I figured that we should at least resolve this,” he remembers. “So I called my secretary and said, ‘Cancel all my appointments. I’m going to L.A.’”

The “this” in question was the night when Elder was in high school, working at the cafe his dad opened with the pennies scraped together from half a lifetime of odd jobs, and the years of bubbling resentment for scoldings and spankings finally burst.

“One day when I was 15, I told myself the next time he yells at me, I’m gonna walk out of the cafe. And I did,” Elder recounts. “My dad came home that night steaming and he asked, ‘Why’d you walk out?’ And for the first time, I spoke back to my father. Well, he balled up the $10 he owed me, threw it at me as I lay on my bed, walked out of my bedroom, and we didn’t have a conversation for 10 years. We did not speak to each other, and it was easy to do it.”

Until, suddenly, it wasn’t.

Landing at LAX, Elder caught a cab directly to the restaurant where his father still worked, walked through the front door, and said, “Dad, I want to talk to you. I’m only gonna be here five or 10 minutes.”

“I was gonna tell him what an SOB I thought he was as a father. I figured he’d call me an ungrateful son, and at that point I’d at least be able to sleep,” Elder remembers. “I told myself to just give him the Cliffs Notes, get it out in five minutes … but my dad sat down and I teed off on him: every spanking, every whipping, every slight. The time he spanked me in front of my best friend, Carl. The time he spanked me in front of my cousin Elaine, who was visiting me from Cleveland. Everything he ever said to me, everything he ever did to me that pissed me off, I told him.

“In 20 minutes, I was out of ammo and my dad said, ‘Is that it? You didn’t speak to me for 10 years because of that?’” Elder continues. “And for the first time, I saw my father cry.”

Seven and a half hours of raw, tearful conversation followed, peeling back layer after layer of resentment from each man at the table until only the uncalloused character of father and son remained.

Randolph Elder, his son soon learned, was a survival story from Georgia’s Jim Crow era, who never knew his biological father and was kicked out of his mother’s house as a teenager at the onset of the Great Depression. He was a Pullman train porter, a World War II Marine veteran, a struggling cook in Tennessee where jobs for Blacks were few and far between. But most importantly, he was a husband and a father who didn’t mind working long hours as a janitor to feed his family until he earned the money to pursue his dreams.

“After eight hours, this man was epic and I got smaller and smaller and smaller,” Elder recalls. He begged his father for forgiveness, and in an act of benevolence, his dad said there was nothing to forgive. Instead, he engraved five pieces of advice onto the softening walls of his son’s heart that Elder says left no room for further self-pity:

—Hard work wins.

—You get out of life what you put into it, Larry.

—You cannot control the outcome, but you are 100% in control of the effort.

—Before you complain about what somebody did to you or said to you, go to the nearest mirror and ask yourself, ‘What could I have done to change the outcome?’

—No matter how good you are or how hard you work, sooner or later bad things are going to happen to you. How you deal with those bad things will tell your mother and me if we raised a man.

That moment, Elder says, began an intimate and rest-of-his-life-long friendship between father and son—and in death, with the same clear and deliberate voice, his father’s instructions speak straight into Elder’s vision for American life.

“The way to deal with somebody who makes an argument you don’t like is with information. You don’t shut him down, that’s just wrong... He has a right to his point of view, and your job if you don’t agree with it is to show why he’s wrong.”

Hand-to-hand

“‘Larry Elder! I hate you, and I love you! Come over here!’”

Elder remembers glancing at the Black man sitting on a fence with cigarette in hand, and thinking, if the guy was gonna shoot me, he’d have shot me by now, so what’s the downside?

“‘I’ve been listening to you now for three, four weeks. At first I couldn’t stand you, but now I see where you’re coming from,’” the man continued, to Elder’s surprise. “‘You’re like castor oil. It don’t taste good going down, but it’s good for you. Keep it up!’”

While Elder has few fans outside the Republican party, he has caught the attention of many. This, he does not mind.

Some, like Brown sociology professor Dr. Prudence Carter, disagree point blank with his opinions on racial wealth disparities. “When it comes to actual economic and academic outcomes, so much of that is determined by the material resources in families,” she explains. And, she asserts, racism is an ongoing factor that continues to be overlooked: “It’s easier to blame the victim, because it de-centers the responsibility for the role of government.”

One of Elder’s Brown classmates, Duke University economist William Darity ’74, coauthored a 2018 report concluding that “the pattern is evident: studying hard and working hard clearly is not enough for Black families to make up for their marginalized financial position.” The study found white households headed by an unemployed person have a significantly higher net worth than Black households with a head working full-time. Meanwhile, Black households headed by a college graduate average less wealth than white families headed by someone without a high school diploma.

Other observers, like the man who accosted Elder, remain perched on the fence.

One lesson Elder says he’s learned from talk radio that he’s prepared to take on the campaign trail is that it’s “hand-to-hand combat sometimes.” He remembers the start of his career in the early ’90s when “almost every other call was from a Black person calling me a sellout or some other name. And my response was always, ‘Tell me what it is that makes you feel that way, what view I have that you don’t like, rather than trying to psychoanalyze who I am.’”

But with a record of callous remarks and unsavory allegations, the presidential hopeful will have to answer not only to his dissenters, but also to his accusers. In response to the brutal beating of Nancy Pelosi’s husband, Paul, by a home invader last October, for example, Elder tweeted, “Poor Paul Pelosi. First, he’s busted for DUI and then gets attacked in his home. Hammered twice in six months.”

Elder also faced accusations of domestic violence from an ex-fiancée and was harshly criticized by many after dismissing a sexual assault allegation on the basis that the woman was not attractive enough to be assaulted. Elder denies these claims and says regarding the sexual assault allegations: “That was a flat-out lie.”

Then, there are some contradictions in Elder’s life that will remain unresolved—such as that, despite being a devout Christian, he is divorced from his ex-wife after they couldn’t agree on whether to have kids. “If I had to do it all over again, I would’ve had the kids,” he says. And that he is happily dating his girlfriend of more than 16 years with no intention to marry, even for the benefit of public image.

Of this, he says, “I just think the personal stuff is not nearly as important as it used to be. But as the campaign gets going and I become a more serious candidate in the minds of other people, I suspect those questions are ones I’m gonna have to deal with.”

However, the vitriol that Elder says was once an automatic within the Black community has waned. Rather than flinging cries of “Uncle Tom!” they quietly disagree. And while there’s no telling whether his emergence on the national stage will reignite a sense of betrayal from his peers, Elder is determined to press on in parenting America the way his parents raised him.

“When I was seven years old, my mother sat me down with an illustrated book of all the presidents from George Washington to then-incumbent Dwight Eisenhower. She went over all their highlights and achievements, and at the end of it, she said, ‘Larry, someday if you want to, you can be in this book,’” Elder recalls. “Well, I never, ever thought I’d run for anything, but I always believed it was doable because of what my mom said: ‘Nobody can make you feel inferior without your permission.’”

Ivy Scott ’21.5, a CASE award-winning former BAM intern, is a criminal justice reporter at the Boston Globe.