Countless Americans are unknowingly living with a time bomb in their head—a small clot of blood cells that will eventually block the flow of blood to the brain and kill millions of neurons. This is known as an ischemic stroke and is one of the leading causes of death and serious long-term disability in adults. One in four people will experience a stroke in their lifetime. That’s about 800,000 Americans annually, or a new stroke victim every minute.

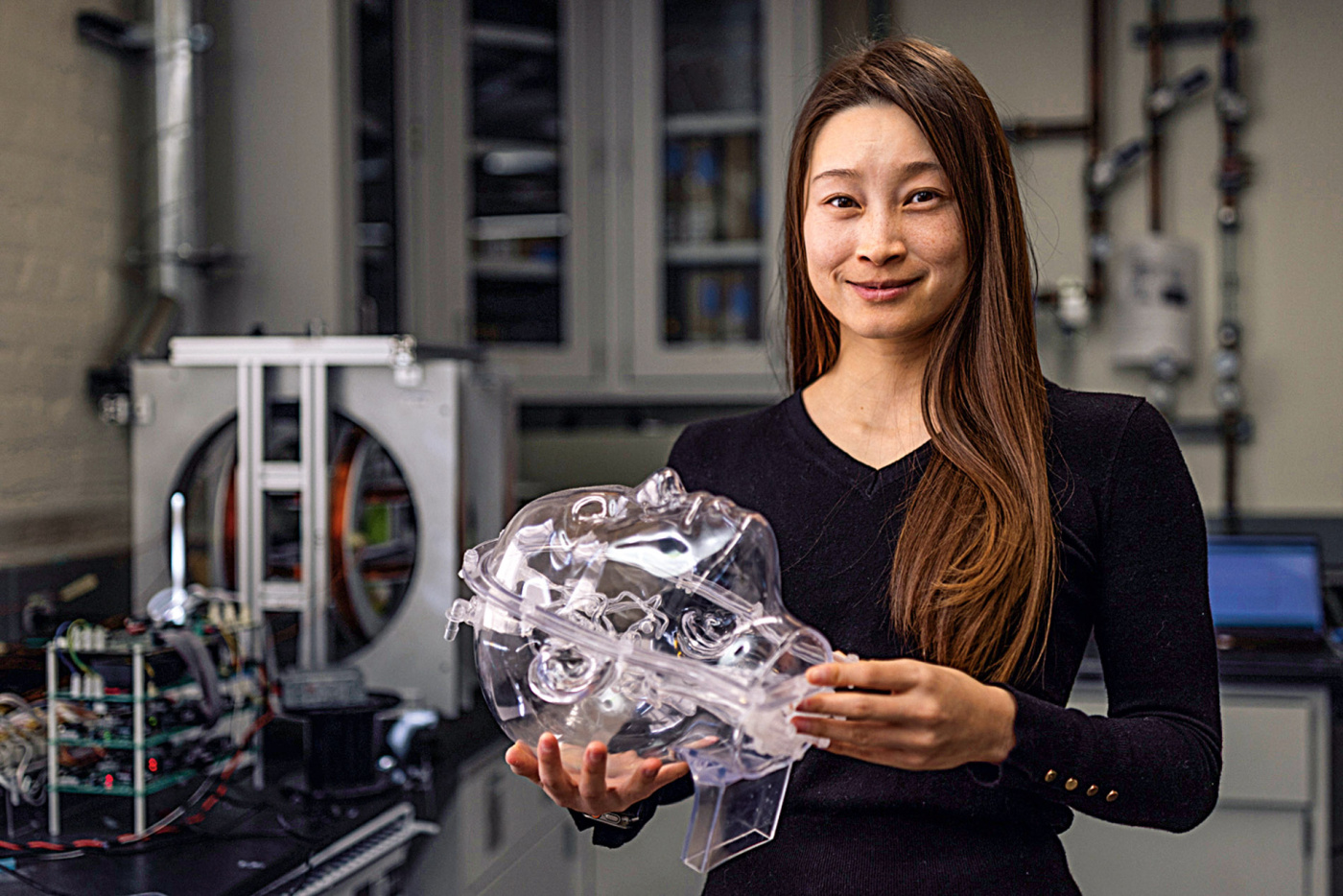

But there’s new hope ahead. Earlier this year, Renee Zhao ’14 ScM, ’16 PhD and her team of researchers at Stanford’s Soft Intelligent Materials laboratory published a paper in Nature unveiling a groundbreaking new approach to treating ischemic strokes that could one day save millions of lives. Her device, called the millispinner, is a robot not much larger than a poppy seed, but in early tests it proved capable of removing blood clots with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

“The conventional way of treating strokes is basically a vacuuming machine,” says Zhao. This technique, known as mechanical thrombectomy, typically involves snaking a catheter through a vein in the patient’s leg up to the clot in their brain. When the catheter reaches the clot, the doctor activates a pump that attempts to suck the clot into the catheter. But, says Zhao, the clot is typically larger than the catheter, which makes it tough to remove. “The failure rate is pretty high, especially when the clot is stiff and tough.”

Zhao’s millispinner overcomes this challenge by compressing the blood clot to a fraction of its original size so that it can easily be sucked into the catheter. The tiny robot, mounted on the end of a conventional thrombectomy catheter, consists of a hollow tube outfitted with rows of fins and slits that cause the tube to rotate in the blood vessel, generating localized suction that holds the clot against the tube. As the millispinner rotates, it dislodges the red blood cells and winds the fibrin—a tough stringy protein that binds the blood cells together—into a dense ball. (Zhao compares this to rolling a ball of cotton between your fingers.)

So far, Zhao and her team have tested the millispinner on pigs with outstanding results and she hopes to see a first human trial as soon as late 2026. Meanwhile, they’re working on a next-generation millispinner that’s routed through the body’s bloodstream using external magnetic fields. This will allow it to reach clots in blood vessels that are too tortuous for a catheter, present in roughly half of ischemic stroke patients.

“The magnetic spinner can basically swim its way to the clot, coupled with an imaging system and controlling algorithm to guide its navigation,” says Zhao. “It’s a long-term project, but it’s exciting because it also opens up other functionalities such as treating brain aneurysms that can lead to a hemorrhage stroke.”