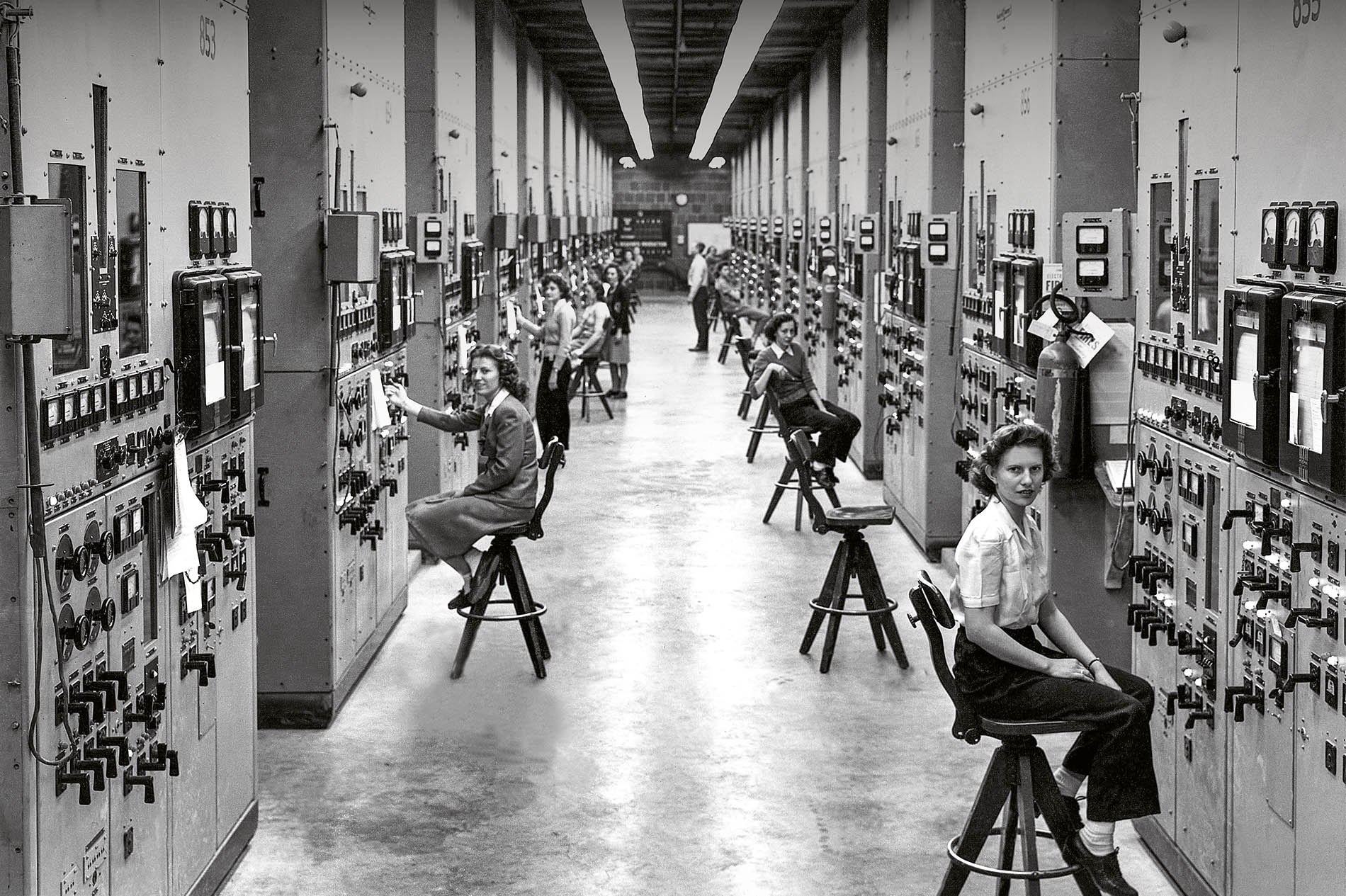

Not Your Idea of a Kodak Moment

A new book explores the photo industry’s dark past.

Movies such as Saving Private Ryan, Dunkirk, and Oppenheimer have dramatized the horrors and heroism of World War II—including the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. In her new book, Tales of a Militant Chemistry, Alice Lovejoy ’01 tells a different kind of war story, about the role film companies themselves played in developing weapons of war. At the same time the United States was fighting Nazi Germany, her book reveals, film giant Kodak was fighting its chief rival, German film and chemical company Agfa, both contributing to their respective war efforts.

In her book, Lovejoy details the surprising story that unfolded on both sides of the Atlantic, including Kodak’s role in the Manhattan Project and the literal and figurative fallout from its efforts as it covered up radioactive rain after the war. While most elements of the book have been mentioned in some way before, albeit often briefly or in passing, this is the first time the full story has been told. “What happens if we think of film not as part of the culture industry, but as part of the chemical industry?” she asks.

Lovejoy became interested in photography in high school, developing film in the darkroom. After graduating from Brown with an independent major in documentary studies and social issues, she worked as a reviewer for Film Comment magazine before moving on to earn a PhD at Yale. Now a professor of cultural studies and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, she discovered the hidden history of film companies and war while researching her first book about the history of a Czechoslovak Army film studio that improbably made experimental films behind the Iron Curtain.

“There was a shortage in film stock during the period, and one of the reasons for that was Kodak’s many military contracts,” she says. Through research in archives in the U.S. and Germany, she uncovered details of Agfa involvement in developing poison gas and explosives, respectively going back to World War I, using chemicals from film production.

Later, the U.S. military asked Kodak to help enrich uranium for the Manhattan Project using centrifuges at its chemical subsidiary, Tennessee Eastman. At the same time, rival Agfa was producing chemical weapons in Germany, using forced labor from concentration camps.

Kodak continued its relationship with the military after the war, helping photograph nuclear tests in Nevada. When radioactive particles showed up while developing film at company headquarters in Rochester, New York, Kodak became part of a secret network of sites to test the flow of harmful radioactive fallout in the atmosphere, even as the larger public was kept in the dark.

“You can see the tension that exists between producing these technologies and living with the consequences of them,” says Lovejoy. Those are questions we’re still grappling with, she says, adding that some factories involved in cell phone production use rare earth minerals from war-torn areas. “It’s part of a larger history about what produces media and what it might mean to make industries more ethical and sustainable.”