On October 28, 2009, I was stationed as a marine lieutenant in southern Afghanistan, enjoying a day off. I had planned to watch the Yankees in game one of the World Series and to write home to friends and family. But everything changed when a sniper team on a routine patrol stepped on a pressure-plate improvised-explosive device (IED).

When I arrived at the scene, very little was clear. In what building were the wounded? Had any casualties already been evacuated? I asked a Navy commander and trauma surgeon on the scene how many casualties he was taking care of. Two, he said. That meant five more were still out there somewhere.

Every option appeared to be a bad one. Words were already coming out of my mouth before I could even process all the information. I pointed down a narrow alleyway where an IED had gone off earlier. "Grab every stretcher we have. We're going down this alley. And stay spread out!"

We managed to load up the casualties. I requested permission to lead the convoy to meet the medevac (medical evacuation) helicopters at the landing zone. Thirty yards into the journey our vehicle struck an IED. It blew off the front end of my vehicle and knocked my turret gunner unconscious.

On any other day my destroyed vehicle and concussed turret gunner would have been my primary concern. But today my only thought was how to get those guys whose lives were fading by the minute to the landing zone. I told my driver to get our latest casualty to medical platoon vehicles and then ordered a few others to stay behind and guard our vehicle.

"What are we doing, sir?" yelled Sergeant Marston.

"Keep going," I yelled back.

I got into a humvee that was heading toward the landing zone. Thirty minutes later, all the bodies were on the helicopters headed back to the primary marine base in southern Afghanistan.

The term fog of war describes a phenomenon unique to armed conflict. It is the intangible force that encompasses the uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity of war. It demands an unconventional thought process in which assessing, deciding, and executing become virtually one action.

At Brown I was taught to research, hypothesize, debate, and advocate. But as a marine officer, I was taught from day one that the cost of indecision is human life. The 70 percent solution right now is better than the 100 percent solution ten minutes from now. You navigate through the fog of war by using whatever information is available to quickly assess and immediately decide.

People often find it surprising that an Ivy League graduate would choose military service over the many other opportunities available to him. But when I reflect on the events of that day in October, I realize how fortunate I am to have had both incredibly valuable experiences. In that alleyway in Afghanistan, I walked away with a skill set at least as valuable as the one I earned at Brown: one that enabled me to navigate the fog of war.

Christopher Rigali is a consultant living in Washington, D.C. He served in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010.

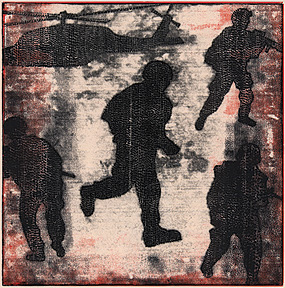

Illustration by Richard Downs.