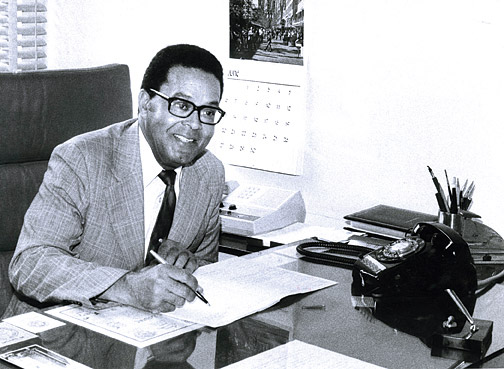

Thomas J. Brown ’50 began climbing the ranks of the Boston business world right after graduation. By 1963, the tall, handsome World War II veteran had become an executive at a top advertising firm. Like most executives, he could have spent all of his spare time playing golf.

Job seekers never paid a fee, and Brown took no salary. He wrote employment listings neatly on index cards and clipped out classified ads to be stored in three-ring binders. The phone was always ringing.

Brown, a former University trustee who received the alumni association’s John S. Hope Award in 1997 for his extraordinary commitment to volunteer public service, died of cancer on June 24. He was 88 and lived in Canton, Mass. A service was held at the Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury.

Key to Brown’s mission was the job he accepted in 1965 as special assistant to Edwin H. Land, founder of the Polaroid Corp. With access to Land’s circles of influential business leaders, Brown, according to his family, turned his position into a bully pulpit for social change.

Brown’s longtime friend Melvin B. Miller, the founder and publisher of Boston’s Bay State Banner—which bills itself as the newspaper of record for the African American communities of Greater Boston—said that Brown’s contributions to his community are immeasurable. “We have a number of black heroes who have done extraordinary things,” Miller says. “Their legacy is written on the souls of the people in a way they don’t even know it’s there.”

Miller and Brown worked quietly to deliver minority candidates for

the jobs Brown unearthed in conversations with executives who claimed

they could not find qualified minorities. Miller would run ads for the

positions in the Banner and then send the candidates over to Brown.

Leon Rock was a high school dropout in 1969 when he wandered over to

Jobs Clearing House. Brown came around his desk and sat with him. He

shepherded him into studying drafting and later recommended him for a

job at Raytheon. Rock’s life was changed forever. “[Brown] was just a

marvelous guy, so down to earth,” recalls Rock, who now lives in

Washington, D.C., where he works as a consultant.

Born in Fall River, Brown was one of five children. Their father worked as a master mechanic. Brown graduated from Durfee High School in 1942, then served three years in the Army. After friends told him about the G.I. Bill, he applied to Brown, where he spent his college years taking part in the Junior Chamber of Commerce and earning a degree in English.

“He always kept you laughing,” says his wife, Inez, a registered nurse who volunteered to work alongside her husband running the employment agency. They were married for 60 years.

“He never took one penny in compensation,” she says. “That’s the

kind of guy he was. You never know what he did for people, because he

wasn’t a person who talked about it.”