It’s hard to imagine today, when headlines trumpet the student loan “crisis” and the record $1.3 trillion of U.S. student debt, that just over a decade ago “nobody was talking about student debt,” says Lauren Asher ’87, the president of The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS). True, people were thinking about it, especially the millions of college graduates whose hard-earned diplomas left them owing multiple thousands of dollars to the government, private lenders, or both. But ten years ago student debt was largely considered a personal burden to be borne in silence, not a policy matter to be debated in the public forum.

“We keep a lot of things private in our culture,” Asher says. “But once you acknowledge something as a trend that affects masses of people, then individuals are more comfortable talking about their situation.”

Acknowledging and giving a name to this trend is precisely what Asher and her organization have done since 2005, when she and a colleague launched TICAS's Project on Student Debt. The nonprofit organization, founded in 2004, has been so successful at changing the cultural conversation around student debt that she has become one of the country’s leading authorities on the topic. Now, when such publications as Forbes, U.S. News & World Report, or the Atlantic publish stories on student debt, they call Asher for a quote. What’s more, in addition to putting the issue of student debt on the national agenda—down to deciding that “student debt” was the best thing to call it—TICAS has successfully pushed for changes in federal policy that have made it easier to apply for, and to repay, student loans.

Asher and TICAS developed the policy model and spearheaded the movement for what became the first widely available income-based student loan repayment plan (IBR) for federal student loans, which caps loan repayments at 10 percent of the borrower’s income and forgives the remainder after twenty to twenty-five years. With IBR, Asher says, “your student loan payments won’t put you in the poorhouse if the economy or job market or your circumstances change, and they won’t follow you to the grave. There’s light at the end of the tunnel.” In 2007, President George W. Bush signed IBR into law as part of the College Cost Reduction and Access Act. Today, Asher says, there are multiple income-driven plans benefiting more than 5.5 million people.

TICAS was also behind the successful campaign to simplify federal student-aid application forms; in 2009, the Obama administration adopted a simplified procedure developed by Asher. “Used to be, you had to hand-transfer data from your tax return,” Asher says. Now, you can apply online, give the IRS permission to share your data, and, with one click, the aid form automatically fills in the required information. Asher, a self-described wonk, gets excited just talking about it. “Things like forms really matter!” she gushes. “That’s where the rubber hits the road.” She points out that a great policy can’t help the people if it’s badly implemented. TICAS has streamlined data in other ways, too: the organization’s annual report on student debt is an invaluable source for journalists and others seeking the latest national and state financial data on higher education—data that, before Asher, was inconsistent and difficult to find.

As its name suggests, however, TICAS also concerns itself more broadly with fostering overall “college access and success,” particularly among lower-income students. In its home state of California, for instance, its “Keeping California’s Promise” initiative has successfully advocated for more grant aid to help low-income community college students with non-tuition costs like books, transportation, and housing, which are essential to staying and succeeding in school.

Asher herself didn’t know a lot about student debt—she was lucky enough to leave Brown unencumbered—when she and Bob Shireman, now a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a New York City–based think tank, began working in San Francisco on a small, grant-funded project intended to raise awareness of the importance of going to college. Shireman, a former colleague of Asher’s, had noticed that billions of taxpayer dollars were being wasted on generous subsidies of federal loans made by private lenders (this program, highly lucrative for the lenders, no longer exists). What else was going on in the student loan industry? he wondered. He got in touch with Asher to see if she was interested in joining him on the project. By then, Asher, who had earned an MPA from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, had several years of experience in nonprofit research, policy development, and communications—and she’d recently left a full-time job. She promptly said yes.

When, from her living-room couch and Shireman’s laundry room, the pair investigated student debt, Asher discovered what she firmly believes is one of the great social justice issues of our time: college access. They found serious disparities in enrollment and graduation along income, race, and ethnic lines. Paying for college has become exponentially more difficult than it was even a generation ago, when an industrious student from a low- or moderate-income household could graduate from a four-year public institution debt-free by working part-time minimum-wage jobs during the school year and full-time during the summers. Today, with rising costs that far outpace income and a dramatic shrinkage in government support for public schools (on the state and federal levels), that scenario is mostly unachievable. While grant aid has increased, it hasn't kept up with what students and their families are being asked to cover. So, in order to earn a degree in four years, that same hard-working student would almost certainly require the addition of a heaping dose of student debt, which has now burgeoned to the point where the average college student in America graduates owing $30,100, according to TICAS’s research. (In 2005, that figure was only $18,550.) Asher found her mission. Call it giving a voice to the voiceless—in this case, young people who want to go to college but have been repeatedly told, in one way or another, that they can’t.“We want to make sure that a quality college education remains within reach of anyone who’s willing to take that leap and work hard.” Asher says.

“We’ve made it much too hard for too many to afford an education without taking on burdensome debt,” she adds. The disparities Asher and Shireman saw in 2005 have only widened since the Great Recession, as the poorest students and their families (not the middle class, as is widely believed) have been most squeezed by rising costs and lowered public investment in higher education. “And what makes debt burdensome isn’t just the number, it’s the kinds of loans you have, your repayment options, and whether you’re actually able to complete your degree and be better off—not just for yourself, but in ways that benefit society. This means being able to get a decent job, support your family, buy a home, start a business, be civically engaged, save for retirement—in short, achieve the American dream.”

Crusading for social justice is pretty much what Asher was raised to do. “I grew up in a cause-related environment,” she says. “My family talked a lot about values and issues, and the importance of working for what you believe in.” Her father worked in the U.S. Department of Justice during the Lyndon Johnson administration and went on to spend the next few decades promoting civil rights and environmentalism. Her mother campaigned for reproductive rights in both the United States and Australia. One stepmother was the director of Volunteers In Service To America (now AmeriCorpsVISTA) during the Carter Administration, while a second stepmother became a prominent advocate for the Zero Population Growth (ZPG) movement and a national leader in public health. So when Asher decided to concentrate in semiotics (as today’s modern culture and media department was then called) and began working in Los Angeles’s film and television industry, her relatives worried she might turn out to be the Alex Keaton of the family—the conservative son, played by Michael J. Fox, of the card-carrying liberal, ex-hippie parents in the eighties sitcom Family Ties. Really, her family wondered: Hollywood?

“I became interested in the cultural production side of things: how do we decide what is interesting and meaningful?” Asher explains, then admits: “I also just loved movies.” In the summer between her junior and senior years at Brown, an internship on a television sitcom—the second TV remake of the movie 9 to 5, where she landed after the indie film she’d come to LA to work on lost its funding—proved to be so much fun that she decided to stay on rather than return to Brown in the fall. That was another move that sent shock waves through her family: her grandmother feared that Asher might even drop out of school.

After a lifetime immersed in the world of progressive politics, Asher did find her new workplace refreshing. “Not that this was the glamorous Hollywood,” she says. “This was the workaday, churning-out-episodes side of the business—smart people trying to make their product as interesting and entertaining as possible. It was a great experience, and I learned a lot: how do things work, how do people treat each other, why do you need to be nice to the assistants? Where does the power flow? How do things end up on TV the way they do? What gets on TV?” To her grandmother’s relief, she returned to Brown and graduated midyear, after writing a semiotics senior thesis on “pro-sex feminism.” Then she went back to Hollywood, her family still skeptical. This time she worked for a sitcom pilot, which never ended up being green-lighted, with the memorable name The Curse of the Corn People. “I’d pick up the phone by saying ‘Curse!’” she recalls, laughing.

Asher found her way back to the family business, as it were, in 1989, as she was waiting for funding to materialize for a film project. One delay led to another, and then another, so Asher signed on for what she thought was a short-term gig helping to make a video for Children Now, a newly formed nonprofit group fighting childhood poverty in California. The organization’s founder, Jim Steyer, who later created Common Sense Media, wanted to try out a then-radical methodology—one that has since been adopted by most nonprofits—that married sophisticated communications with top-quality research and policy advocacy. “The blend,” as it was dubbed by Children Now’s codirectors Laurie Lipper and Wendy Lazarus, found in Asher a near-perfect fit.

“We weren’t going to have a research department, a policy department, and a communications department,” says Lipper, who with Lazarus went on to found The Children’s Partnership, which, with impressive prescience, issued the first national report on kids and digital media in 1994.

Asher was not only able to research and figure out a complex policy issue; she also knew how to turn that complex issue into a hot topic. “Lauren has top-notch ‘classic’ skills: analytic and research ability, written and oral communication. That’s the science,” Lipper says. “But the second part is an art—and Lauren exemplifies it— of being able to see, ‘Here are all these young people suffering, and, as important as it is, it’s not part of a collective discussion. How do we connect that to a policy agenda?’”

If Asher’s bosses were dazzled, Asher was equally excited to be back in the social justice arena. “Hollywood was fascinating, but it always felt a little like visiting a foreign country,” she says. Working for Children Now “felt right—like I’d come home, which in a way I had.”

With the encouragement of her colleagues, Asher earned her MPA from the Kennedy School in 1994, then moved to Washington, D.C., where she worked at the U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau on the recently enacted Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and other women-in-the-workplace research and policy issues. There, Asher pocketed a host of smaller lessons that have proved crucial in her subsequent work, especially at TICAS: the need for forms to be simple, for instance, if you want people to fill them out; the importance of explaining what phrases such as “must be employed full-time” actually mean; and the efficacy of humanizing what might otherwise be an abstraction.

When the Women’s Bureau released a big study on working women, says Karen Nussbaum, who was its director at the time, “it was Lauren’s job to find the perfect woman to represent 300,000 respondents.” Asher found that perfect voice in “a Republican mother in Florida who wrote a letter on her kid’s school notebook paper to go with her survey,” Nussbaum remembers. “It said, ‘I’m writing this after I’ve put my kids to bed on the only paper I can find.’ The woman ended up telling her story—about the challenges of balancing work and family—to President Clinton at a White House event releasing the survey results.”

Eventually, Asher gravitated back to California, this time to San Francisco, where, after a two-year stint in communications with the Kaiser Family Foundation, she ended up helping Shireman with the Project for Student Debt. Like Lipper, Shireman praises Asher’s analytic skills and her ability to get the public engaged. In the case of the student loan problem, she did that with one small adjustment of the camera lens: she suggested that, instead of the common term student loans, which carried the whiff of a promissory note, they use student debt, which implied a collective social problem that was everybody’s concern. With a simple change of phrase, Shireman says, Asher changed the public’s perception.

“I was a wonky flack,” Asher admits, with a self-deprecating laugh. “Now I’m a flack-y wonk.”

Shireman was the founder and first president of TICAS. But after he joined the Obama administration in 2009 (where one of his key achievements was getting the simplified Financial Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, which had been developed by Asher, officially adopted), TICAS’s board of directors unanimously elected Asher to succeed him as president.

Today, TICAS is headquartered in a bustling office in downtown Oakland (with a satellite office in Washington, D.C.), across San Francisco Bay from Asher’s home in San Francisco’s Inner Sunset neighborhood, where she lives with Winton Davies, a computer scientist at Google, and their 9-year-old son, Elliot. (Davies, who was born in Wales, recently became a U.S. citizen and voted in his first presidential election in November.) Last summer, Asher observed two major milestones: her fiftieth birthday and the end of TICAS’s tenth anniversary year.

Over the last eleven years, the organization has not only opened up and broadened public awareness and discussion of student debt; its efforts have been crucial in transforming the rules of the game. There are now strong consumer protections in place, including the income-based repayment (or IBR) plans. The federal government, which itself profits from the student loans it issues (earning as much as $66 billion between 2007 and 2012, according to Senator Elizabeth Warren), no longer subsidizes private lenders at taxpayer expense, and no longer protects those lenders from risk by guaranteeing the student loans they make. (Private loans are still marketed to unwary consumers, however. They lack the protections of federal loans and are, Asher says, “no more a form of student aid than a credit card or a mortgage” and .)

Perhaps most hopeful is the progress TICAS has made in promoting grants over loans. The organization has been a longtime advocate for strengthening the Pell Grant program, established in 1972, which is currently helping more than 8 million of the neediest families to pay for college. (They still cover only 29 percent of today’s college costs, however.) And TICAS has worked hard to spread the word to Pell-eligible students to make sure they find and fill out the applications. Most recently, in California, where budget cuts and stagnation have been prevalent for the last decade, the organization and its partners have managed to increase state funding for Cal Grants by $100 million.

Asher’s latest victory was less dramatic but in keeping with her belief that increasing access means making the paperwork clear and easy to understand. Because federal student aid application forms required tax information for the current year, a student using the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form, which used to be made available January 1, often didn’t have the required family tax information until April, when tax returns are done. Also, aid is often granted on a first-come, first-served basis, and many students need to know their aid package before they can pick a school—and many college applications were due before January 1, when the financial aid form was available. “It was a very irrational process,” Asher says, “that was especially burdensome for some families who most needed aid.”

Thanks to the work of TICAS, however, as of fall 2016 the forms are made available October 1, and require the previous year’s tax data. “This kind of process stuff, I know it’s crazy, but I love it!”Asher says. She does sometimes get teased for being such a wonk: “I’ve been told that I used to be a FMLA [Family Medical Leave Act] bore, and now I’m a FAFSA bore.”

With such solid and wide-ranging accomplishments under her belt at TICAS, could Asher, who calls herself a “social policy generalist who’s become a specialist,” be casting about for that Next Big Issue percolating just below public awareness? Asher pauses—perhaps pondering just what that issue might be—then shakes her head. “I love my work,” she says. “It’s not boring. And it’s not done.”

Lorraine Glennon is an award-winning magazine editor and writer who lives in Brooklyn, New York.

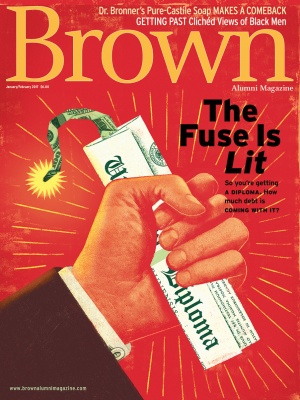

Illustration by Curt Merlo