Fighting for Their Future

From College Hill to Capitol Hill, Lauren Maunus ’19 and Emma Bouton ’20 have been on the front lines of the growing youth movement to shake us out of our carbon-emission status quo before global warming goes nuclear.

As police zip-tied their hands, Lauren Maunus ’19 and Emma Bouton ’20 began to sing. And they were not alone. Throughout House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office, the dozens of young people who had gathered there to call for meaningful climate action elevated their voices in a communion of courage.

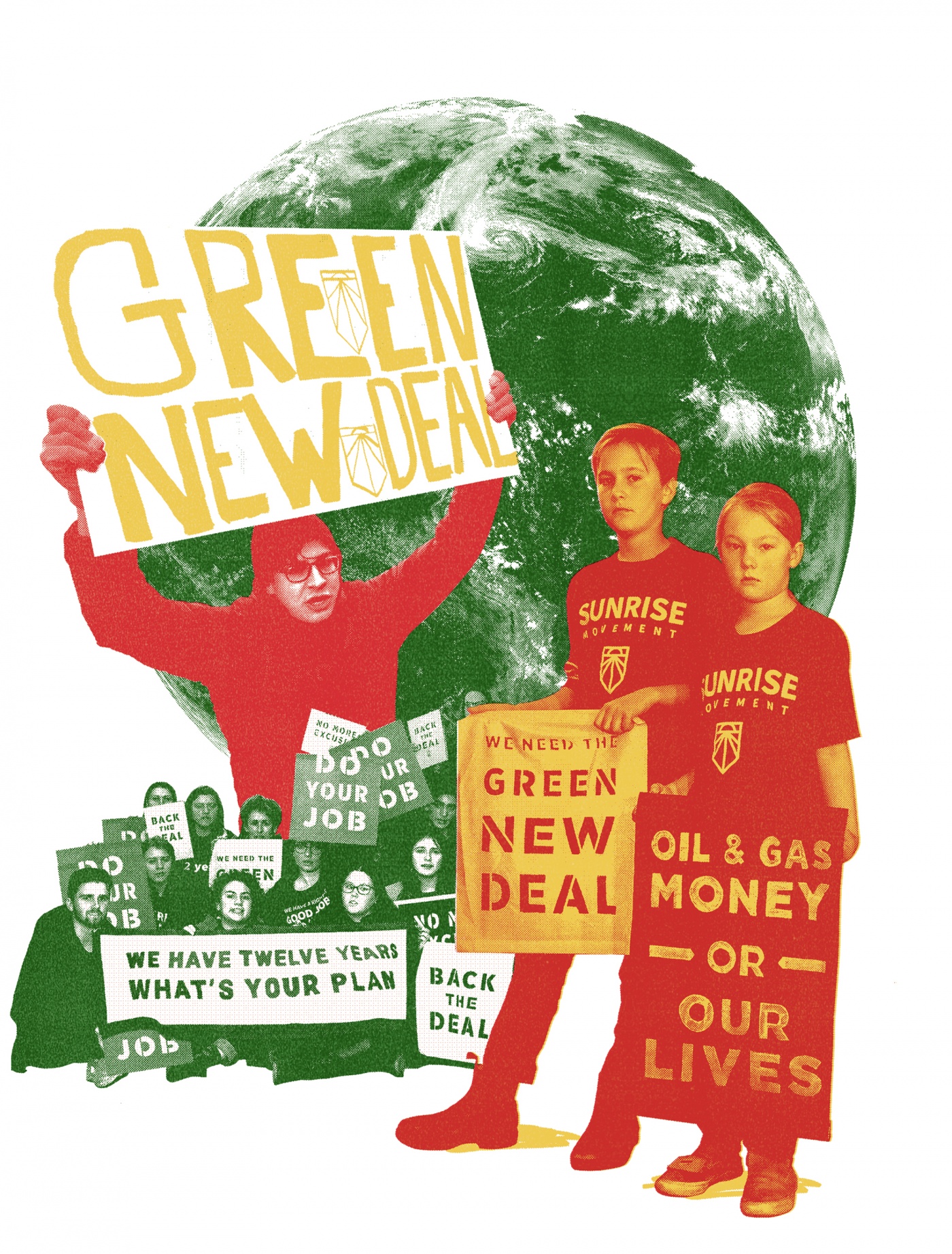

Some protests die in the dark, but on that day in mid-November of 2018, Maunus, Bouton, and dozens of others occupying Pelosi’s office pierced the consciousness of mainstream media and politics, injecting a renewed urgency into the climate crisis. They were part of the Sunrise Movement, a national coalition of young people dedicated to rallying the support and pressure necessary for politicians to take action against climate change. Sunrise advocates for a Green New Deal (see pages 24 and 25), a vision for massive mobilization to decarbonize the economy in the next ten years, while ensuring a “just transition” by providing millions of well-paying green jobs and confronting systemic racial, social, and economic injustices.

“Sitting in that office I felt the most powerful I’d ever been,” Bouton says. “It was incredible to be around other young people fighting so intentionally for this better future.”

A little over a month before the 2018 sit-in, a United Nations–sponsored international committee of scientists had warned that the world needed to prevent global temperatures from rising above an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) to avoid catastrophic and irreversible environmental consequences, which could begin within the next twenty years. Global temperatures are currently set to rise 3 to 5 degrees Celsius by 2100. The report called for immediate action to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030 and eliminate 100 percent of emissions by 2050, relative to preindustrial levels.

Yet despite the report’s dire warnings of trillions in damages and hundreds of millions dead, the new House majority under Pelosi’s leadership had not listed climate change as one of its priorities. Trump and much of the GOP, meanwhile, denied human-induced global warming altogether.

“We need an active base of people always showing up, being loud. We need to build that people power.”

“We were trying to be as loud and furious as possible but also as hopeful as possible,” Maunus recalls. “Pelosi has the power to change what climate politics looks like. We wanted her to stand with us and take the crisis as seriously as we do.”

After newly-elected Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez joined the Sunrise protest in Pelosi’s office on her first day of Congressional orientation, people started to take notice. Now, a growing number of Democratic members of Congress have signed on in support of a non-binding resolution to consider building a blueprint for a Green New Deal. All leading Democratic presidential candidates also support the Green New Deal’s framework and many, like Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Joe Biden, have released their own ambitious climate action plans. By this point it’s clear that the Sunrise Movement has catalyzed a new level of discourse—it’s the primary reason CNN hosted seven hours of televised presidential interviews in a September town hall focused solely on climate change. During the 2016 Presidential debates, in contrast, candidates talked for less than six minutes about climate change.

For Maunus and Bouton, the journey to Pelosi’s office parallels the increasing politicization of climate change and the rise of a new generation of activists committed to saving the world.

Lauren Maunus has lobbied for legislation since before she could drive. Her younger sister, Rachel, has a deadly tree nut allergy—and Florida, where the Maunus sisters grew up, did not require schools to identify allergens in the meals they served. For Rachel to buy lunch in the school cafeteria, her mother had to drive all the way to the district’s headquarters to scrutinize each menu’s ingredient list. So, at 13, Maunus drafted a mock bill for her Youth in Government club to require schools to clearly label ingredients; at a statewide contest, it won first place. Inspired—and despite feedback from local legislators, who told her the idea would be too costly—she talked with food service directors, advocated at county meetings, and networked with legislative aides to catch the ear of politicians. Her policy became part of statewide guidelines, and in 2015, was included in the reauthorization of the USDA Child Nutrition Act.

She’d learned what it took to make things happen.

Once at Brown, Maunus threw herself into climate organizing, motivated by the unnatural toxic algae clinging to the waterways back home in Palm City, fed by runoff chemicals from local agricultural companies. Attending the 2017 United Nations Climate Conference in Germany as part of an environmental science seminar, she was discouraged by the discovery that the only U.S.-sponsored event would be a panel discussion featuring—almost exclusively—fossil fuel executives.

“I felt completely unrepresented by my own government,” Maunus recalls.

She learned that an international climate activism group planned to disrupt the panel and recruited her fellow students to join. Midway through the discussion, over half of the room stood up and began to sing, halting proceedings.

“That was the first moment that I felt my voice resounding with voices all around me and felt what building power meant,” Maunus says. “I knew I needed to hold on to what that felt like, to bring it back to campus and Rhode Island.”

Maunus soon worked to align the Rhode Island Student Climate Coalition—a local organization struggling to find direction—with the newly emergent Sunrise, a national movement that inspired Maunus with its strategic vision. Eventually, she would manage to involve students from schools all over the state by pushing to start the first Sunrise group in Rhode Island. It was one of only a few across the country at the time.

“This is a small state, but no one had been successful at connecting the various universities here,” says environmental studies Professor J. Timmons Roberts. “Lauren saw the potential in this group and has done what no student has done in the past decade of trying—she’s led the building of a real statewide coalition of students.”

Emma Bouton still remembers the force and fear of the hurricane. A freshman in high school when Sandy struck New Jersey, Bouton and her family evacuated to her grandparents’ home. They didn’t know where her aunt was, nor how other friends were doing. Bouton’s grandma realized she had only a couple of days’ worth of an important medication. Everything ended up being okay for Bouton’s family, though not for many others who were left homeless or dead.

“That was a wake-up call for me,” Bouton says, “in terms of what a future could look like if these kinds of storms continued.”

Like Maunus, Bouton attended the 2017 climate negotiations and served as an active member in the Rhode Island Student Climate Coalition, but the sit-in last year at Pelosi’s office proved to be a turning point. As Bouton and the other protestors prepared for the action the night before, Ocasio-Cortez and fellow freshman progressive representative Rashida Tlaib made a surprise appearance. Their message, according to Bouton: “We have people on our side, giving us the power to be bold. We need you to bring the moral clarity of the public to Congress to allow us to uphold all that we promised in our campaigns and that you worked so hard for.”

Later, Bouton called her parents and told them she planned to risk arrest. The phone went silent. Bouton explained her reasons and how the arrests fit in to a larger strategic vision—the need to catch media attention, to show complacent politicians that the public demanded action, the urgency to do something. After a while, her parents said they understood. They told her they supported her, and loved her, and wanted her to be safe. She slept fitfully under the pews that night.

In a U.N. report last year, scientists warned that without radical reductions in our carbon emissions, catastrophic and irreversible environmental consequences could begin within the next 20 years.

The next day, with a Jolly Rancher from Representative Tlaib still in her pocket, Bouton and the other Sunrise protestors entered the Congressional offices with signs hidden in backpacks. As they flooded into Pelosi’s office, Bouton remembers looking up at a television on the wall showing coverage of the apocalyptic California wildfires, the most destructive and deadly ever recorded in Pelosi’s home state—a catastrophe that scientists reported would only be repeated as the environment became hotter and drier.

“We need to tell her [Pelosi] that we’ve got her back in showing and pursuing the most progressive energy agenda that this country has ever seen,” Ocasio-Cortez told the protestors, as TV cameras rolled with footage that would soon go viral.

Once so shy she barely spoke in class, Bouton is now comfortable grilling politicians in front of hundreds of people and delivering impromptu testimony before the state legislature.

While a majority of Americans believe human-induced climate change is real, a common frustration is “Well, what can I do about it?” Yet a Harvard study frequently cited by Sunrise found that only 3.5 percent of the population needs to actively participate in a nonviolent social movement to generate serious political change. In the U.S., that would mean around 11 to 12 million people.

“We need an active base of people always showing up, being loud,” Maunus says. “We need to build that people power, where most people see themselves as part of the solution.”

So they kept at it. A few weeks after the sit-in at Pelosi’s office, Maunus and Bouton brought 40 students to D.C. to join more than one thousand protestors targeting specific legislators. Activists crowded into the Capitol Hill office of Massachusetts representative Jim McGovern, with Maunus at the front of the livestreamed surprise attack.

They asked if McGovern would support a committee on the Green New Deal and its main goals. McGovern assured them all he was on board: “We can do that.”

“So you can tweet your support?” Maunus asked. “Can you do that before we all leave here today?”

McGovern said he would do it soon. “If not, come back and storm…” he added, meekly.

“Oh, we’ll be here,” Maunus responded, as everyone applauded. They waited.

The tweet was sent and the endorsement by a prominent Congressman became public and official.

Earlier, at the same protest, Bouton led over a dozen Rhode Islanders into the office of one of the state’s two representatives, David Cicilline ’83, explaining why they wanted him to sign on to the resolution for a Green New Deal. Though Cicilline was out of the office, his aides listened, and soon after, with prodding on social media, Cicilline became a cosponsor of the resolution and has since remained a vocal ally.

Most politicians aren’t so willing to endorse bold climate action.

Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo, who has accepted thousands of fossil-fuel connected campaign donations, rejected a pledge to refuse campaign donations from fossil fuel companies after Bouton confronted her with it. Bouton and Maunus later marched out on a snowy morning to picket a fundraiser for Raimondo hosted by a law firm representing a company seeking to make a billion-dollar investment in a natural gas power plant. (A Raimondo spokesperson later said the law firm had been a long-time supporter of the Governor, and the fundraiser had “nothing to do” with the company.) The power plant would have prevented Rhode Island from meeting non-binding carbon-emission reductions Raimondo had set several years before, according to the Conservation Law Foundation.

The two inexhaustible activists have also rallied Sunrise to ask Democratic National Committee Chairman Tom Perez ’83 to reinstitute a party-wide ban on accepting donations from the political organizations of fossil fuel companies. The ban was reversed two months after it was instituted in the summer of 2018, with Perez explaining at the time that the DNC maintains a strong commitment to climate action but wants its “big tent” to have room for workers in the fossil fuel industries. After repeatedly interrupting Perez’s on-campus speaking events, Bouton journeyed all the way to Block Island by ferry in August, infiltrating an intimate fundraiser with Perez. She unfurled a Sunrise banner and asked him in front of his guests: How many lives lost to natural disasters and climate migration would it take before the DNC agreed to allow a Presidential climate-change debate? On the Facebook livestream of the “birddog”—when politicians are put publicly on the spot by activists—Perez did not have a response. Later, a DNC spokesperson told the BAM that the DNC “doesn’t get money from the fossil fuel industry,” or “accept money that is not in line with our values.” Regarding a debate, the spokesman said the climate crisis is “a central part of our platform,” but that the organization voted to stick to its “policy of holding debate focused on multiple issues,” while making it clear that “climate change must be featured prominently.”

Maunus, Bouton, and Sunrise RI are waging their most contentious fight against Rhode Island’s Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, who has long positioned himself as a leading champion of climate action. Whitehouse recently gave his 250th speech on the Senate floor on the threat and has been an outspoken critic on the influence of the fossil fuel industry in politics. He appears an unlikely adversary.

But his ideas focus primarily on political compromise and market-driven solutions, as evidenced by The American Opportunity Carbon Fee Act he introduced earlier this year, aimed at reducing emissions by putting a price on carbon pollution.

“Easy, moderate solutions are no longer adequate. They would have been possible if we had started thirty years ago.”

It’s a clash of visions: Whitehouse wants climate reform. Maunus and Bouton, and the growing movement they’re part of, seek a revolution.

“The old way of thinking hasn’t worked,” Maunus says. “They’ve been making these decisions since we were infants—or not even born. To think we can stay in the status quo is disrespectful and nonsensical.”

Carbon taxes have received substantial support for many years. The basic premise is simple: Force companies to pay for the hidden costs of carbon emissions and they’ll deal with the problem in the most efficient way. Just this January, a Wall Street Journal editorial signed by 3,554 U.S. economists, including Alan Greenspan and Janet Yellen ’67, stated that a carbon tax would be “the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary.”

But the idea may no longer be a solution—at least not on its own. Take the idea for a carbon tax in Rhode Island, starting at $15 per ton of carbon emissions, with increases each year. Maunus and Professor Roberts both lobbied for it. But like similar efforts across the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, it has yet to pass. (“It’s hard to mobilize people around a tax,” Roberts says).

Even if carbon taxes did become law, the U.N. says governments would now need to impose a tax of up to $5,500 per ton of carbon emissions by 2030 to prevent the irreversible effects of climate change. And an economic analysis of the Rhode Island carbon tax found that it would get the state only a third of the way to zero emissions, Roberts says.

“That’s the point that I think my generation and older generations need to hear,” Roberts adds. “Easy, moderate solutions are no longer adequate. They would have been possible if we had started thirty years ago.”

Maunus, Bouton, and the rest of the Sunrise Movement in Rhode Island have long sought to convince Senator Whitehouse—in private meetings and public protests—that the Green New Deal framework represents the most effective way to meet the scale and scope of the climate crisis. Yet when the resolution came before the Senate in March, every Republican voted against it and every Democrat—including Whitehouse—abstained to avoid an inter-party divide. The framework lives on in Presidential platforms and other Congressional proposals.

One year ago, Sunrise Rhode Island had no political clout and fewer members than a cozy seminar. Today, its members could easily fill a large lecture hall and have demanded the attention of every major politician in the state.

In early September, hundreds of Sunrise supporters from all over the East Coast converged on Providence for a national summit that was hosted by the several Rhode Island Sunrise groups now in existence.

They didn’t end up in Providence by chance. Bouton, Maunus, and fellow Sunrise leader Matthew Mellea ’21 had spent the whole spring semester analyzing the history and theory of social change, from the Civil Rights movement to Occupy, after creating their own independent study. By May, they’d developed a comprehensive two-year plan for expanding the Sunrise movement across the state, ramping up pressure on political leaders, and recruiting and training other young people. Over the summer, Sunrise leaders had helped plan the September summit, supported by fellowship grants for which Bouton and Mellea had raised funds.

On the final day of the summit, more than two hundred activists crowded into the Rhode Island State House to call for Governor Raimondo to support a Green New Deal for the state. Raimondo didn’t talk to them that day. And she didn’t talk to them a few weeks later when they stormed the State House once more as part of the Global Youth Climate Strike. But the activists believe she won’t be able to keep ignoring them forever. Asked for comment, the governor’s press secretary, Josh Block ’14, didn’t mention a Green New Deal, but he said climate “is one of Governor Raimondo’s top priorities.”

Maunus—now a deputy political coordinator for the national Sunrise Movement—and Bouton see their work so far as just the beginning. They know the planet needs climate action. They know what they are up against. And they know no one ever changed the world by embracing the status quo.

“We are scared,” Maunus says. “We are hopeful. But we are not backing down from relentlessly demanding the solutions we need to solve this crisis.”

See ri.sunrisemovement.

Jack Brook ’19 has also reported for the Marshall Project, the Miami Herald and the Providence Journal, and received the University’s 2019 Betsy Amanda Lehman ’77 Award for Excellence in Journalism. He attended a Sunrise protest in D.C. last winter.