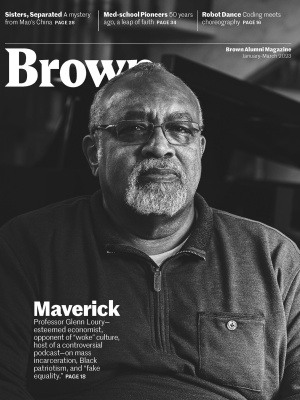

Maverick.

Professor Glenn Loury is a leading conservative voice in America, from his home base at Brown. In this wide-ranging conversation in Loury’s living room, Pushcart Prize–winning poet and ardent progressive Ravi Shankar discovers nuanced differences and unexpected alignments.

Maverick, iconoclast, and provocateur, over the decades the 74-year-old African American economist—who is the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences at Brown University—has made numerous controversial pronouncements about race in the United States. In The Chronicle of Higher Education, he asserted that “Affirmative Action Is Not About Equality. It’s About Covering Ass”; he’s called structural racism “a bluff and a bludgeon…an empty category” and the Black Lives Matter movement “a gross distortion of reality”; and in a recent article making the case for Black patriotism, he asserts that “our Americanness is much more important than our Blackness.” He has become one of the most important conservative thinkers alive today and a public intellectual not afraid to change his own mind and challenge his own champions.

Loury’s journey is remarkable. Raised in a poor Black family on Chicago’s South Side, he became an unwed father in his teens and dropped out of school, only to be discovered at a community college, where he earned a scholarship to Northwestern University. He would go on to train in economics at MIT, pioneering concepts such as “social capital,” the web of connections that precondition economic success, and “stigma” as differentiated from discrimination. Upon finishing his dissertation, he became the first African American to secure tenure in Harvard University’s department of economics. He was even under consideration to be Undersecretary of Education for the Reagan administration but withdrew his name from consideration when he was charged with assault in a domestic dispute (the accuser later dropped the charges) and arrested for cocaine possession.

Since then, he found (and questioned) God, then accepted a chaired professorship to direct the Institute on Race and Social Division at Boston University before departing for Brown, where he has taught since 2005. He has embraced new media, creating a popular weekly Substack program, The Glenn Show, where he has proven himself one of the few commentators in America who can converse with self-proclaimed non-Marxist socialist Cornel West as well as purportedly white supremacist sociologist Charles Murray, treating both with consideration and respect, even when disagreeing with many of their premises.

Therefore, as someone seemingly on the opposing side of the political spectrum from Professor Loury, it was with equal measures of trepidation and curious interest that I visited him in his high-ceilinged, gabled-roofed home on Providence’s East Side. Over the course of the next few hours, we discussed race, policing, bias, patriotism, spirituality, and more [full transcript here], and I found Glenn to be voluble and vulnerable, much more open and nuanced in his viewpoint than I had presupposed. I knew that we both shared an interest in issues of racial inequality and the problems of mass incarceration, my own experience of which I detail in my 2022 memoir Correctional, but given the climate surrounding the overturning of Roe v. Wade and numerous other ostensibly partisan decisions by the highest court in the land, I wanted to begin with his recent full-throated open letter denouncing the attacks on Justice Clarence Thomas, whom he deems “among the pantheon of Black trailblazers throughout American history and a model of integrity, scholarship, steadfastness, resilience, and commitment to the Constitution of the United States of America.”

Ravi Shankar Thanks for having me over, Glenn. Let’s begin with your recent open letter in support of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, whom the New Yorker has called “the most powerful Black man in America.” I read your letter, which to be fair was not about his jurisprudence but about the problem of assassinating the character of someone whose opinion we don’t agree with, even going so far as calling him a race traitor and an Uncle Tom. Reading your words immediately made me wonder what it might be like for you as a professor at a place like Brown. Is it a comfortable space? Do you get pushback from your colleagues and students?”

Glenn Loury I wish I got more. I feel a little bit ignored really. My perspective has always been one of open inquiry. Not just in the case of Justice Thomas, but regarding the larger set of questions about how we talk with each other in public, what’s permitted to be said and what’s being self-censored as political correctness.

Shankar How about your students?

Loury Well, first off, the students in my classes are self-selected. I’m not teaching any classes that are requirements. I teach a class in the economics department on race and inequality and a seminar on free inquiry in the modern world. We read classical texts and discuss them, and I put pressure on their prevailing suppositions. And nowhere has anyone suggested that my views about the political issues of the day, if conservative, are unacceptable, injurious, and illegitimate for me to express. Still, I can’t help but think that if I were not Black I’d have a much harder time.

Let me be concrete. Let’s look at the Black family as a social institution. Let’s look at the out-of-wedlock births and the prevalence of single parent families. Let’s look at violence in the inner cities. Sociologists may not readily admit this, but the structure of the family is actually very important for social outcomes. While this is a complex cultural phenomenon under the influence of historical forces and larger economic and social dynamics, they are nonetheless reflective of the internal constitution of the community. Part of our problem regarding the gaps of academic achievement are attributable to what is valued by the Black family.

I can say this. But if someone like Amy Wax [the University of Pennsylvania law professor who has seen her academic position come under duress for making inflammatory comments about race and sexuality in the classroom] repeats the same thing, she’s a racist. Part of the racial inequality in this country is not just due to redlining or slavery, or Jim Crow or whatever, but it’s also due to cultural patterns that are evident and consequential and divergent across different population aggregates. I repeat this with respect to affirmative action. If you’re transitioning from a culture of Black exclusion, you may want to rely upon some preferential methods as a temporary, stop-gap mechanism. However, ultimately, we cannot ignore the underlying fundamental developmental deficits that are causing these inequalities. Using preferential selection criteria is a cover-up for the consequences of the historical failure to develop African American performance fully. It’s fake equality.

Shankar One thing I really appreciate about you, Glenn, is that you are willing to take an unpopular stance and defend it with logic. Despite what others may have inferred about you, I sense a deep humanism and even a tentative optimism in your work. Is that part of the case you are making for Black patriotism?

Loury: “Woke racialism claims the American Dream doesn’t apply to Blacks, which is a patronizing lie.”

Loury Look—here we are. We’re African Americans but we are Americans first. We are not African in any way that’s meaningful. Yes, our ancestors may have been enslaved, but they were also emancipated. We are literally the richest and most powerful people of African descent on the entire planet. We have ten times the income on average of the typical Nigerian. There’s an enormous Black middle class and Black billionaires. Woke racialism claims the American Dream doesn’t apply to Blacks, which is a patronizing lie that robs us of agency and authenticity and self-determination and dignity. It doesn’t acknowledge that we possess the ability to rise to meet our challenges and carry the torch of freedom.

Shankar Then would you buy into the narrative of American exceptionalism? That there’s something about our collective democratic experiment that makes this country somehow both different and perhaps categorically better?

Loury Listen, I would never be a chest thumping, jingoistic, flag waving, America’s-the-greatest-civilization-that-has-ever-existed blowhard. America is the Vietnam War and capitalism run amok. Certainly, there are legitimate critiques that could be made about our foreign and domestic policies. However, I wouldn’t be shy about affirming the greatness of the American civilization. The ratification of the Constitution and the framing of the structures of government here are remarkable and we can observe that when people get to vote with their feet and move around, they don’t mind coming here. A lot of immigrants arrive here and prosper, wave after wave after wave, which I put forth as tangible proof of the virtue and value of this civilization.

Shankar What’s problematic for me are the illusions and elisions and coercions and inaccuracies that go into sustaining this myth. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson used the model of consensus governance and a written constitution taken from the over 800-year history of the Iroquois in framing their drafts of the United States Constitution. And in India, where my parents emigrated from, there was a functional participatory democracy as early as the 6th century B.C. Yet somehow, we consider ourselves unique. I see an inability to think critically and empathetically.

Loury Fair enough.

Shankar My perspective is also colored by the experience of my father, who immigrated here in the mid-1960s; as you know, we’ve had a raft of discriminatory immigration policies in our country, from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the Immigration Act of 1924, which used eugenics to justify restrictions on Asian immigration. It was not until the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that someone like my father was allowed to come to America at all and that was only because he was studying to be a mechanical engineer.

And speaking of India, I think of how for all its chaos and corruption, it is really a vibrant living model of secular democracy. Where my grandfather grew up in Coimbatore, there was a local election to city council, and I think there were over one hundred candidates on the ballot. It’s messy and overwhelming, but also more reflective of the great range of belief on the political spectrum. I’m curious what you would make of Noam Chomsky’s assertion that in the U.S., there’s basically one party—the business party?

Loury That happens to be the fervently held position of the lovely lady I’m married to now. We go back and forth—she claims that all the culture war kerfuffle is just deep cover for the common consensus affirmation of the structure of society where the wealthy and corporations get away with low to no taxes, little environmental obligations, etc. And the difference between the Republicans and the Do Nothing Democrats is thinner than we imagine. That’s her posture—not mine. I’m a staunch defender of capitalism.

I take scholars like Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson seriously; their book Why Nations Fail explores the beneficial power of the inclusive institutions that maintain a civil border in which free enterprise thrives. This is not capitalism without restraint, not a system of governance without taxes and environmental regulation, not a society without a social safety net, etc. When I look at Scandinavia and Northern Europe, I see capitalist countries with a social democratic framework, but I don’t see public ownership of the means of production, I don’t see the censorship of media, and those other elements.

Shankar Then, however we choose to define it, we agree that a more empathetic model might be more beneficial to its citizens? Take your example of Scandinavia—there’s a reason that life expectancy and measures of contentment are higher there than in the United States, where our healthcare system is in shambles and there’s rampant inequality. When you look at these other models that have a more vigorous and robust social net and less income disparity between its citizens, isn’t that something we should look to as an example?

Loury Sure, why not? Let’s lay out the pros and cons thereof. I was impressed by a body of research done by Italian political economist Alberto Alesina, who coauthored a paper on the survival of the city with Harvard sociologist Edward Glaeser. The paper asks why there isn’t a European-style welfare state in America. First, they argue, many of these societies were more ethnically homogeneous and therefore better able to sustain a political compact of mutuality—we’re all in this together. And that race was a bind. In fact, it was a fractional factor that made it more politically difficult to generate consensus around the idea that we’re all in this together and it feeds into the fear from the typical voter who may believe that higher taxes and a greater social provision is going to benefit the undeserving who will disproportionately be Black. This is one of the arguments and part of the account, although I don’t think it explains it fully.

Shankar Let’s get back to the question of race and mass incarceration, which I know you have done a lot of writing on and which my memoir Correctional is about. Why is it that we have 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its incarcerated people? More than North Korea and Iran and China combined. Why are our rates of recidivism so high? How can we ignore the racial disparity in sentencing and how the explosion in prison growth during the last 40 years has been mind-boggling?

Loury I’ve written about this in a book, Race, Incarceration, and American Values. At that time, I was in a rage about the over-incarceration of African Americans in the United States. The bottom line is that we rely on the punitive reaction to social disorder to an extent that is unrivaled in world history. But I also said that this can’t be the end of the discussion. We need to ask about the root causes and living conditions and family structures of those who have ended up in prison.

Shankar Based on my experience the institution itself fosters dysregulation, not rehabilitation. It feels like an investment in failure. We have been discussing Norway—there are no life sentences there, so they are incentivized to help heal those who have committed crimes. These people are given a trade, access to mental health counselors, and relative freedom. But here we believe in punishment.

Loury: “We have been over-investing in incarceration…. Punishment doesn’t do anything to restore and make the victim whole.”

Loury We have been over-investing in incarceration and we don’t have any expectation that the process of confinement is going to be to the betterment of a criminal. We’re punishing them so it’s meant to be punitive. You could make an argument on the other side that asks: Why should we have a social policy that invests in education and healthcare and general life enhancements of the quality of life for someone in prison? Why should you have to break the law first before being eligible for the benefits of such policies? It begs the question: If I’m doing this for the incarcerated, why am I not doing it for everybody?

Shankar It seems we are getting it all wrong—over-incarcerating those who have mental health issues or drug problems instead of addressing their underlying issues. Isn’t it punishment enough to be away from your friends and family in confinement? Do you really need the casual sadism of the correctional officers, or the neglect of health needs, that only will make it harder for you to reintegrate into society? How about the ripple effect that mass incarceration has had on generations of families?

Loury There’s a political scientist at Johns Hopkins, Vesla Weaver, who coined this term “frontlash” about how punishment and surveillance have been used to circumvent civil rights advances. In the 1960s you had the end of Jim Crow and consensus within American politics that we are going a different direction on the race question. There were winners and losers in that shift. So when there were race riots and cities in which the reaction was disorder, they could enact policies that sublimated concerns about racial dynamics into seemingly colorblind concerns about crime. That’s one argument.

But something is missing, which is that there was a lot of support within communities of color for punitive responses to the upsurge in crime and violence that one sees through the 1970s and the 1980s. For example, the crack versus powder cocaine sentencing disparity is well documented. It was about how much weight would trigger a mandatory minimum prison sentence and it was a 100 to one ratio. You can argue that it was racially disparate punishment. But a lot of Black representatives supported it. We see that echoed in the argument about “defund the police” and so on. [Black people] live in urban communities where there are murders and carjackings and robberies and so on. The residents want more police. Of course, they want police who are not going to abuse them, because they are outraged by police violence and police brutality. But they want something to answer when they call 911. Because they’re the ones who are suffering the consequences of most of the violent crime that goes on in the cities.

I’m complicating the simple story that after the end of slavery, you had the Black codes and southern states not wanting to accept the citizenship status of the newly free Blacks, which led to the rise in the incarcerated population, and then at the end of the civil rights movement in the 1970s you are seeing this rise in incarceration. I think that’s too simplistic. Still my outrage is reflected in that book I wrote and what it says about American values that we sit idly by while under our watch there is this institutional transformation which is truly historic, going from a half million to 2 million under lock and key in a 20-year period. We basically allowed it to happen, allowing politicians to run for office waving a banner saying I’m going to lock them up, three strikes and you are out, mandatory minimums, super predators…

Shankar Don’t forget about “law and order.” For some reason, I always found that the most chilling euphemism. Why do you think we aren’t more forgiving as a people?

Loury It’s what it is. I mean, the incarcerated are disqualified from housing benefits, from Pell grants, support for post-secondary education, certain jobs, the list goes on. In some jurisdictions they are prevented from being able to cast a ballot. They’re basically excommunicated. I agree with you but discussing it is not enough. Here’s something I’ve been doing in response to questions like this.

There’s a gentleman named Johnny Pippins, who is serving an expected 30 years at Iowa’s Anamosa State Penitentiary for felony murder. During his time in prison, he’s completely reformed himself, gotten a college degree, gotten a master’s degree, and been accepted to a PhD program. However, to pursue a PhD program, he needs to be on campus. He can’t do it remotely.

I’m proud to be able to use the little network around my Substack newsletter to try to get the word out on this. We decided that we would try to bring this case to the attention of Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker. We have gotten hundreds of signatories to a letter. We say, listen: This is an exceptional case. He has paid his debt, now let him contribute to society. Recently the Chicago Sun-Times ran an editorial appealing to the governor to do exactly what we suggested.

Shankar I’ve been working with the formerly incarcerated on reentry and there’s this sense that if you have a misdemeanor or a felony conviction, it’s going to follow you for the rest of your life. You should be happy flipping burgers. I struggle wondering if we’re inherently uncharitable.

Loury Yeah, I don’t have an answer on that. And especially when you consider that in some of the quarters that are most conservative, they’re also most religious and they’re Christian. And you might think that that Christian charity orientation would militate in favor of a more charitable response to social transgression.

I served for years on the board of Prison Fellowship ministries. The organization’s model was Christ hanging on the cross being crucified, forgiving the guy next to him who is a common thief or whatever. You get saved through Christ and I don’t think you have to believe in the magic of people going to heaven to see the metaphor that’s built into that story, which is what we believe as Christians. It requires us to adopt a more charitable posture. You’re not defined by your worst moment in your life.

No one’s arguing for a kind of disarmament of society and its effort to protect itself against the depredations of wrongdoers. But that’s not the end of the story. That’s the beginning of the story. And oh, by the way, how are victims helped by the punitive reaction to the criminal? Punishment doesn’t do anything to restore and make the victim whole. And what about the people who are connected by bonds of blood and identity to the people who are being punished? What about their families? What about their children? We’re creating social policy here, not just doing a kind of one-off balancing of right or wrong for the individual. To make people’s lives better, you don’t just want to target those who have broken the law. You want to make the intervention earlier.

Shankar Let’s talk about racial stigma, as opposed to discrimination, which you elucidated so beautifully in your Anatomy of Racial Inequality, which I believe was just reissued. How do you think those ideas hold up 20 years down the road?

Loury I’m proud that I was one of the first few people to make this argument, which comes out of my understanding of race. I see race as these marks on our bodies that we use to casually sort strangers into various groups. Then we react to what we see, not our knowledge or understanding of people. Race is embodied social signification, so what the marks mean depends on whether you are in the deep South or New England, in sub-Saharan Africa or in Brazil. When we think of citizenship, we think of law and you can change the law to create Emancipation and write civil rights bills, but you can’t change the stigma. Individuals in society depend on not just the rule of law but social connectivity.

Shankar What you call “social capital”?

Loury Yes. And therein is the social meaning of your racial category. This undercurrent of thinking those who are different from me don’t fit with me. They’re unintelligent. I wouldn’t want intimacy with them. I don’t want to live next to them. I don’t want my children in school with them. They’re ignorant. Dirty. Unworthy. That’s what I’m trying to get at with racial stigma. I’m saying the culture and the history have an overhang in which the social meanings attached to bodily marks for African Americans impede our full inclusion within the web of interconnection and intermarriage and integration into certain neighborhoods.

Shankar I can see the difference between your mode of thinking and what conservatives refer to as a ‘colorblind’ approach. Ultimately, what I most admire about your work is that you are returning agency to individual actors in some way. Rather than human lives being solely contingent on these historical forces, which makes certain communities into victims, you’re empowering people with the ability to make their own decisions, while simultaneously acknowledging the kind of historical underpinning and context in which these lives are led.

Why don’t we end with spirituality? Because along the margins of a lot of what you say I feel the resonance of the spiritual path you’ve been on, maybe lapsed, maybe coming back around to it. Do I have that right?

Loury That’s a big question for me these days. I was once born again. Bible believing, praying, church attending. But [ultimately] I didn’t buy it. I’m a rationalist. I don’t believe in life after death. I don’t think a man was raised from the dead. I think that’s a fairy tale. I fell away from the church. But that was in 2000, over 20 years ago. But now, you know, I’m thinking about mortality. Can you live without faith in something? I am unsure these days. My lovely wife is an avowed atheist.

Shankar Wasn’t she raised Seventh- day Adventist?

Loury Yes, and it was very strict, and she broke away from that in her 30s. She and I met in 2016. So it’s been about six years now. We’ve been married for four years. And when we talk about this kind of thing, she’s a little wary that down underneath my hyperrationality there’s still this quest for something. And she may be right about that. Let’s just say I don’t know how the story ends.

Ravi Shankar Ph.D. is a creative writing professor, translator, and Pushcart Prize–winning poet. His memoir Correctional was published in 2021.