On a September afternoon more than three years ago, I gave my first speech to the Brown community at Opening Convocation. The theme was the importance of constructive irreverence in university life: the willingness to break intellectual boundaries and challenge conventional wisdom, while striving to appreciate and build on the ideas of others.

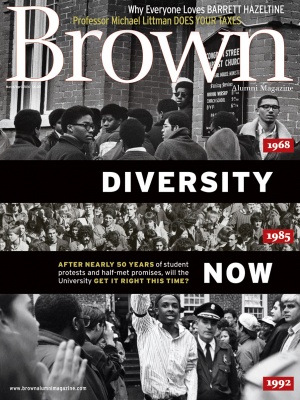

Although talking about constructive irreverence is easy, fostering a community both irreverent and respectful can be a challenge, as we’ve seen in recent protests at Brown for greater racial justice. These protests are rooted in longstanding and widely shared concerns that Brown has not made sufficient progress in supporting the academic aspirations of students from groups that have been historically underrepresented in higher education.

Media coverage of these protests reflects sharp divides in how student activism is understood, and divergent opinions about what the protests signify. A common thread is that something has gone awry in higher education, and that the demands of student activists are pulling universities like Brown away from their missions of open inquiry and the advancement of knowledge. This view misses two key points.

First, advances in media mean that irreverence is captured and propagated today for all to see. At Brown’s 1798 Commencement, a student named James Tallmadge spoke passionately and persuasively in support of abolition. His audience included members of the Brown Corporation who were in the slave-trading business—the very people who would grant Tallmadge his college degree. If this audacious act had been captured on iPhones and posted on YouTube for the eighteenth-century world to see, I am certain it would have generated the same divided opinions as video clips of twenty-first-century student protests.

The problem now is that the world sees the irreverence and not the full breadth of discussions about race taking place. At Brown, faculty, students, staff, and alumni have worked for more than a year on plans to promote a more diverse and inclusive campus, components of which are already in place. The actions in the February 1 Pathways to Diversity and Inclusion plan reflect countless conversations.

I and other university leaders at Brown met with many people eager to address these issues as well as others who need assurance that creating a more diverse and inclusive community is consonant with our commitment to academic excellence. These conversations helped Brown hone thoughtful, forward-looking plans. And this work, born of constructive irreverence, is preparing all students to lead in the complex settings they’ll encounter after graduation.

This leads to the second point: that the goals at the center of discussions about campus diversity are consistent with Brown’s mission to educate and advance knowledge. The University recruits the best and brightest students—rich and poor, from all racial and ethnic groups and nationalities, and with varying political perspectives and religious beliefs—who have the drive to become leaders in their fields. And the faculty members who teach them represent a broad range of backgrounds and experiences.

Diversity contributes to a vibrant intellectual environment where constructive irreverence flourishes. The status quo is more likely to be challenged when individuals do not share the same beliefs. Learning from others is enhanced when community members have different backgrounds. The range of subjects researched and taught increases when faculty view the world differently. It’s our charge to ensure that everyone at Brown has the resources to thrive and impact the world.

The unfortunate reality is that eliminating racial inequities is difficult work. Inequity is too deeply ingrained in our social, economic, and educational structures for quick fixes. But we stand at a moment of opportunity. Brown alone cannot solve the problems of racism and discrimination, but we can be a vanguard in cultivating the thoughtful conversations that move us forward. We can build a diverse and inclusive community that graduates students who go on to create new business models, new forms of creative expression, and new social movements that serve society.