If Cecile Richards ’80 had wanted to take some time off after 12 enormously eventful years at the helm of Planned Parenthood, people probably would have understood. It can’t have been easy to have walked in her shoes, they’d likely think, to be at the center of one political storm after another, and be simultaneously revered as an intrepid champion of women and reproductive rights and vilified as a crusader for safe and legal abortion.

And if Richards, 61, were simply exhausted at this fraught moment in time, when access to women’s reproductive health care is in peril, when the U.S. Supreme Court may soon reconsider the 45-year-old Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion, and when the exhilarating hope of an ally in the White House—the first woman president to boot—has given way to official antagonism toward the 101-year-old organization, her allies could surely relate. Plenty of them must be feeling that way too.

Yet to hear Richards tell it, she’s not feeling beaten down, but pumped up. As she travels the country to promote her new book, Make Trouble—a deeply detailed memoir that’s also a how-to guide for coping, carrying on, and creating change—she tells routinely packed houses of mostly women that we’re living in a golden age, something akin to her own childhood in Texas, where her progressive parents and their tight community of fellow activists taught her not to shy away from fighting the powers-that-be.

“I think we are in the total heyday of activism right now, unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” she told one such crowd in Nashville this spring.

The long view

Richards knows a thing or two about putting in the work. While she rose to national prominence during her tenure at the helm of Planned Parenthood, she’s spent decades in the arena, fighting not just for reproductive rights but for the whole galaxy of issues affecting those she sees as on the weaker end of the power equation. Planned Parenthood, which she left at the end of April, was a culmination of a lifetime spent protesting, agitating, and organizing.

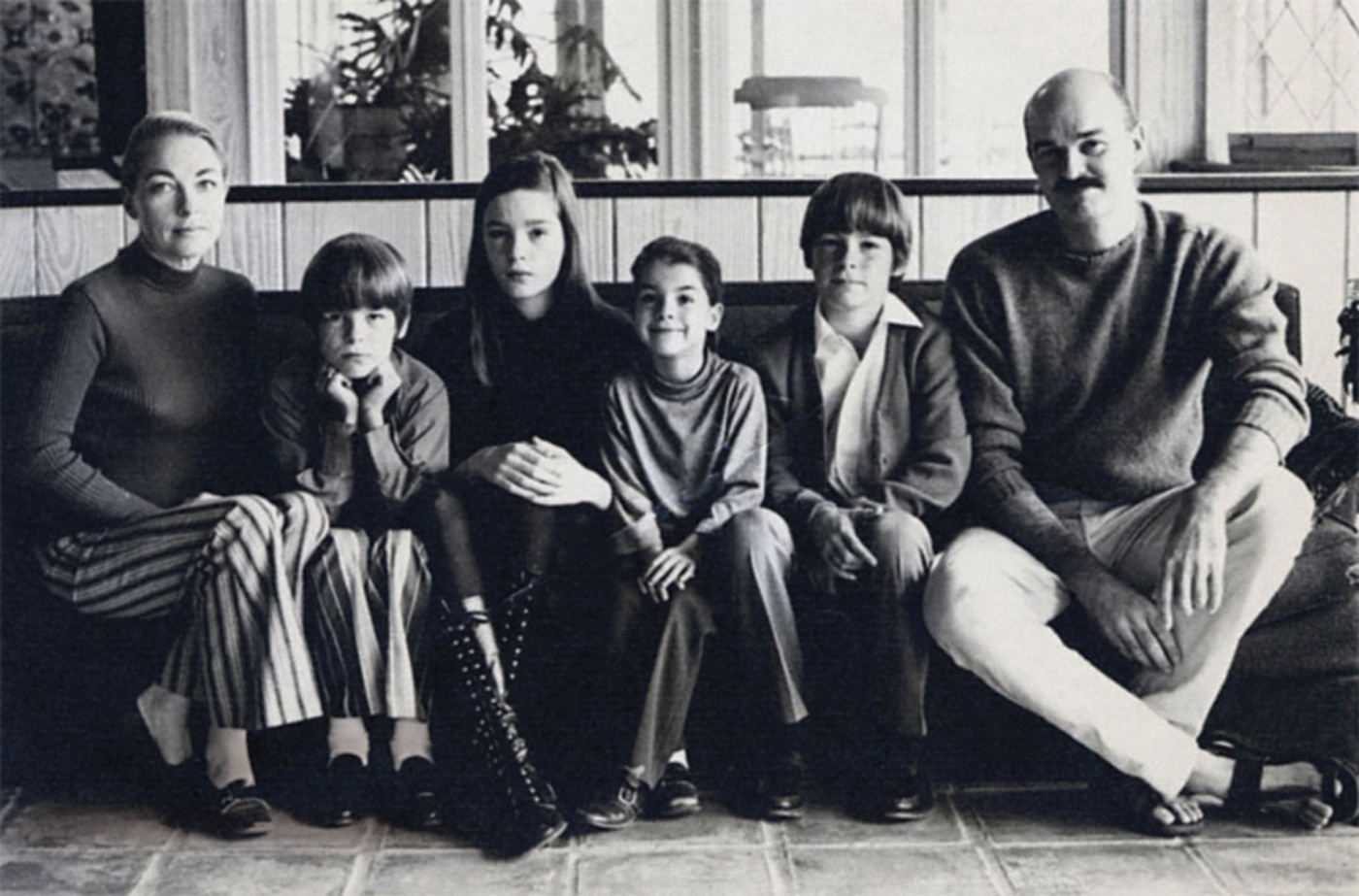

The oldest child of progressive parents in conservative Texas—including mother Ann, a sharp-witted, carpool-driving mom who would go on to become a one-term governor and feminist icon—Richards honed her passion for activism at Brown, got her feet wet as a labor organizer, campaigned for her mother when she ran for Texas governor, and spent time working for Nancy Pelosi before taking the Planned Parenthood job that cemented her reputation as one of the nation’s preeminent advocates for reproductive health and rights.

In fact, Richards thinks of herself more as an “equal opportunity organizer,” one who learned through all these experiences how the fight for social and economic justice is intertwined with the battle for health care and reproductive rights.

“Like a lot of folks, I feel like I just did the next thing that needed doing,” she told the audience in Nashville. “To me, going to Planned Parenthood was a natural extension. The same folks I organized in hotels in New Orleans, or janitors in Los Angeles, or nursing home workers in East Texas, they’re the folks that rely on Planned Parenthood, too. People come to us for reproductive health care but they need a lot of other things. They need a living wage. They need child care that’s affordable. If they’re immigrants, they need us to stand with them. To me that’s the exciting thing about the organization.”

Dawn Laguens, Planned Parenthood’s executive vice president, said that along with Richards’s energy—she called her the “Energizer bunny” of organizers—that perspective has been key to her effectiveness as an advocate. Lots of people now talk about “intersectionality,” a popular buzzword describing how race, class, and gender create advantage and disadvantage, Laguens said. But Richards “saw the connectedness before.”

If her work gave Richards an unusually broad perspective, it also gave her a long one.

She’s not unrealistic about the current situation. The past few years have seen her fending off misconduct accusations based on undercover videotapes purporting to show that Planned Parenthood officials sold fetal body parts (Richards apologized for the officials’ cavalier tone but said the allegations were unfounded, a conclusion backed up by several probes). She’s battled onerous abortion restrictions coming out of various states, such as bans on specific procedures and clinic regulations passed under the guise of safety that abortion-rights supporters say are really designed to impose practical roadblocks. She’s been front and center in defending the hard-fought victories of the Affordable Care Act—not just free access to all forms of birth control, but other benefits that make life easier for women such as affordable coverage for those with pre-existing conditions and guaranteed maternity coverage. She’s also dealt with multiple attempts to “defund” the organization, moves that would target Medicaid patients who get their care from Planned Parenthood and a program called Title X, which subsidizes contraceptives and other preventive services.

She’s horrified by the “corrosive” control of government by one party, by the administration’s actions on a range of issues and Congress’s capitulation, and by a move to pack federal courts—and the U.S. Supreme Court—with judges who could overturn Roe v. Wade. She said she thinks anti-abortion advocates’ goal is to return control to the states, “so there are some states where it’s safe to be a woman and some states where it’s not.”

“Some of these circuit courts are going to get much, much harder and much, much worse for women. So we have to change who’s in office. That’s the bottom line,” she said.

Bargaining women’s rights

One particularly sobering wake-up call came three months after the candidate for whom she’d spent months campaigning, Hillary Clinton, conceded. Richards, as she recounted in her book and in her interview with BAM, found herself at a Trump-branded New Jersey golf club. She was face-to-face with Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, the daughter and son-in-law of the new president and, more importantly, potential emissaries to a regime that seemed to view Planned Parenthood not as a healthcare provider to one in five women, but as a political football. Joining Richards was her husband, Kirk Adams, a labor movement official; she figured she might want a witness.

The meeting had been arranged through common acquaintances, at a time when some Clinton supporters still held out hope that the reputedly moderately minded couple could influence the president. Richards was skeptical—she’d seen what happened after Al Gore took a meeting with the president-elect at Trump Tower, only to watch Trump summarily dismiss Gore’s climate agenda—but she had a plan: at least try to explain what Planned Parenthood did, who it helped, why it mattered, how its work and the policies it supported, including in the Affordable Care Act that the Republicans were vowing to quickly dismantle, had led to fewer teenage pregnancies and abortions.

Kushner had a plan too, Richards says. He was looking to cut a deal.

After reminding Richards that Republicans controlled the entire government and that she had no bargaining power (and after Ivanka complained that Richards hadn’t been nicer when her father said good things about Planned Parenthood in passing), Kushner made a take-it-or-leave-it offer: if Planned Parenthood would just stop performing abortions—a small part of its mission and one that receives no federal funding, but that Richards deems “critical” to giving women control over their own destinies—he’d lean on Congress’s leaders to call off their quest to defund Planned Parenthood. Kushner even floated the idea that funding could increase.

“If it wasn’t crystal clear before then, it was now,” Richards wrote. “Jared and Ivanka were there for one reason: to deliver a political win. In their eyes, if they could stop Planned Parenthood from providing abortions, it would confirm their reputation as savvy dealmakers. It was surreal, essentially being asked to barter away women’s rights for more money.”

Organizing 101

Despite all this, if you listen to Richards talk, it’s hard to miss a loud note of optimism. It comes from the knowledge, learned over time, that activism is a long slog beset with moral victories and repeated defeats. Looking on the bright side “is the classic organizer approach, or else you’d do something less stressful,” she said. It comes from having lived through the Obama era, when even a friendly president told progressive supporters that “whatever you need done you’re going to have to make me do it,” as she recounts. But mostly, it comes from the outpouring she’s seeing now.

Her book, written with former Planned Parenthood speechwriter Lauren Peterson and published by Simon & Schuster, is partly a response to the moment, and to the people who’ve approached her since the election saying they wanted to do something but didn’t know what. The bad news, she said in an interview at her Nashville hotel, is that there’s no one answer. The good news is that there are many ways to act.

So Make Trouble is field guide as much as autobiography. It brims with intimate stories about Richards’s life, and with hard-earned, blunt-spoken wisdom from her famous mother, whose life story Richards feels has never been fully chronicled. It features an entire chapter on her Brown years, where she arrived as a Southwestern misfit, discovered her voice as a student activist, and left having found her life’s work (“I may have majored in history but I minored in agitating,” she wrote). It imparts lots of life lessons learned along the way: this is a once-in-a-lifetime moment to decide who we are. Once you start questioning authority, it’s hard to stop. Don’t sit around and wait for the perfect opportunity to come along—find something and make it an opportunity. If you’re not scaring yourself, you’re probably not doing enough.

She likens the book events themselves to tent revivals, chances for people to channel their frustration and connect with others who feel the way they do. Each is staged with a different interviewer—Hillary Clinton in Westchester, the millennial comic Jessica Williams in New York, Nancy Northup ’81, president of the Center for Reproductive Rights and recipient of a Brown honorary degree this year, in New Jersey. In Nashville in May, it was novelist and local bookseller Ann Patchett, who bemoaned the state of the country, worried aloud about Richards’s personal safety—Richards said she’s much more likely to hear from people who are grateful to Planned Parenthood than those who oppose it—and delved deep into Richards’s backstory. Among the things she wanted to know: did Richards’s liberal Texas parents have any friends?

Actually, said Richards, they did—not the casual type but the sort that you want to be in the bunker with. Their home base was the progressive-leaning Unitarian Church, and “it was a pretty magical childhood, actually,” she said.

Finding her tribe

Richards was born in Waco, but she grew up in Dallas—where her father, attorney David Richards, and her mother were continually swimming against the predominant tides—and later in Austin, a relative nirvana. At 13, Richards had her first of many run-ins with authority when she wore a black armband to school in solidarity with anti-Vietnam War protesters and got called to the principal’s office. The experience, she recalled, was scary but exhilarating, particularly when her mother heard what had happened and was furious on her behalf.

Brown crossed her radar when she saw a magazine article about a student takeover of an administration building and realized it was a place where “things were really happening.” She arrived in the fall of 1975 with a mom-selected woolen wardrobe of skirts and turtlenecks, which Ann Richards figured was what people in New England wore but which Cecile said made her feel like a character out of Little Women. She struggled to fit in with preppy Northeastern classmates who wore topsiders and rugby shirts and listened to unfamiliar music such as the Chieftains and John Martyn, not the country music that was popular back in Texas. She eventually found her tribe on the picket line on behalf of the school’s striking janitors and librarians.

From there, Richards went on to protest for Brown’s divestment from the racist South African apartheid regime and against the Seabrook, New Hampshire, nuclear plant. She moved into the Milhous co-op, where the ambitious group meals she cooked on her nights—a remnant of her southern roots—were a step up from the usual utilitarian lentils. A semester off landed her in the heart of the women’s movement, working in Washington for full enactment of Title IX. Yet, as graduation neared, she felt like an outsider again when some of her fellow activists gravitated toward more traditional careers. She was just getting started.

Those were rough years back home. It was the ’70s and her mother was venturing from a supporting role into a starring one, running first for local office and later for state treasurer. That, and a drinking problem Ann Richards had yet to confront, put a strain on her parents’ marriage, which didn’t survive.

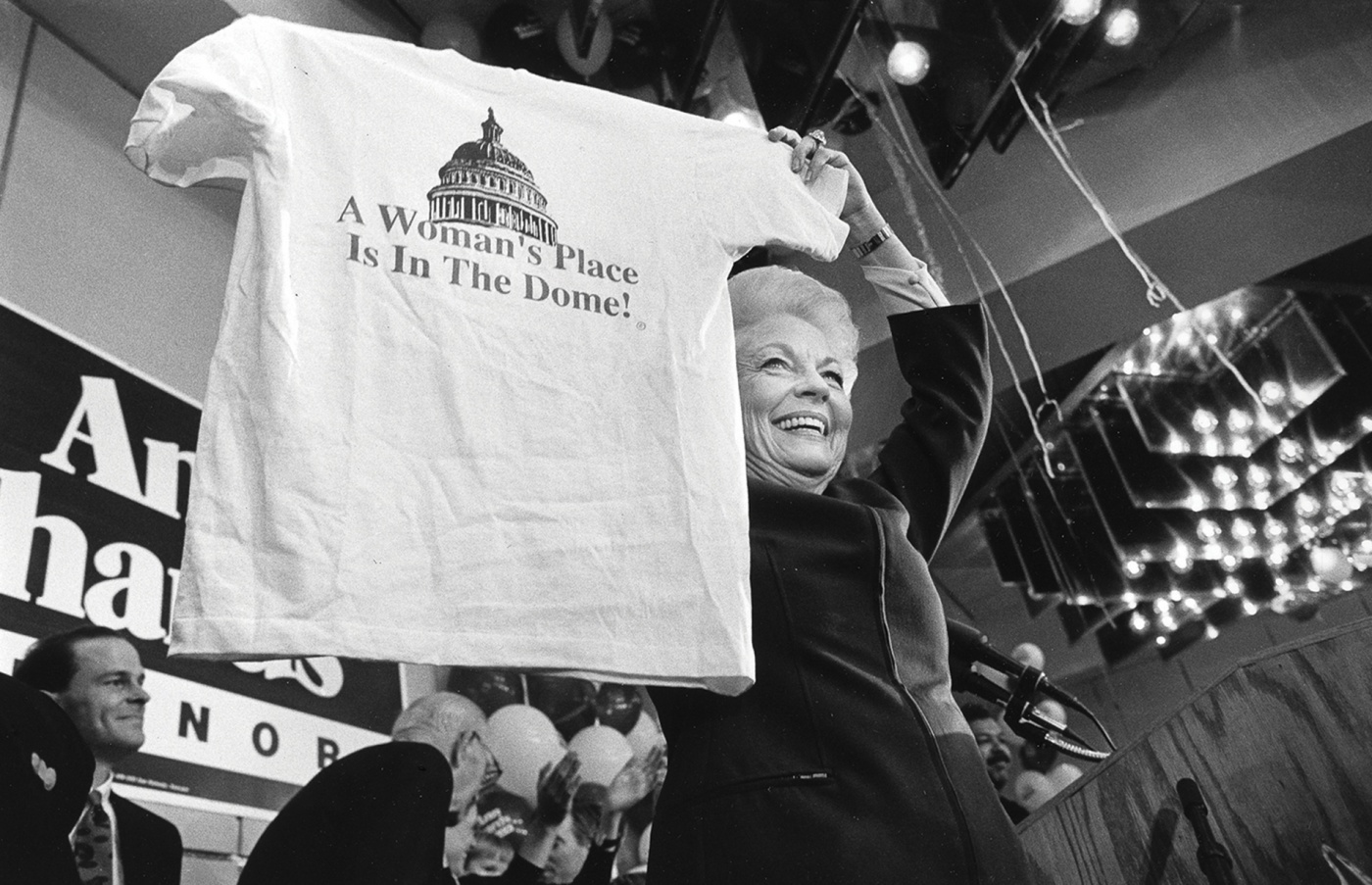

It wasn’t until eight years after Cecile graduated, at the 1988 Democratic convention, that Ann Richards, then state treasurer of Texas, became a mid-life overnight sensation with a single, instantly legendary takedown of the oft-tongue tied George H.W. Bush, the sitting vice president who had won the Republican Party’s nomination. Sporting a hive of white hair and with a gleam in her eye, Ann Richards let rip in her best bless-his-heart tone: “Poor George, he can’t help it. He was born with a silver foot in his mouth.”

Life after Brown

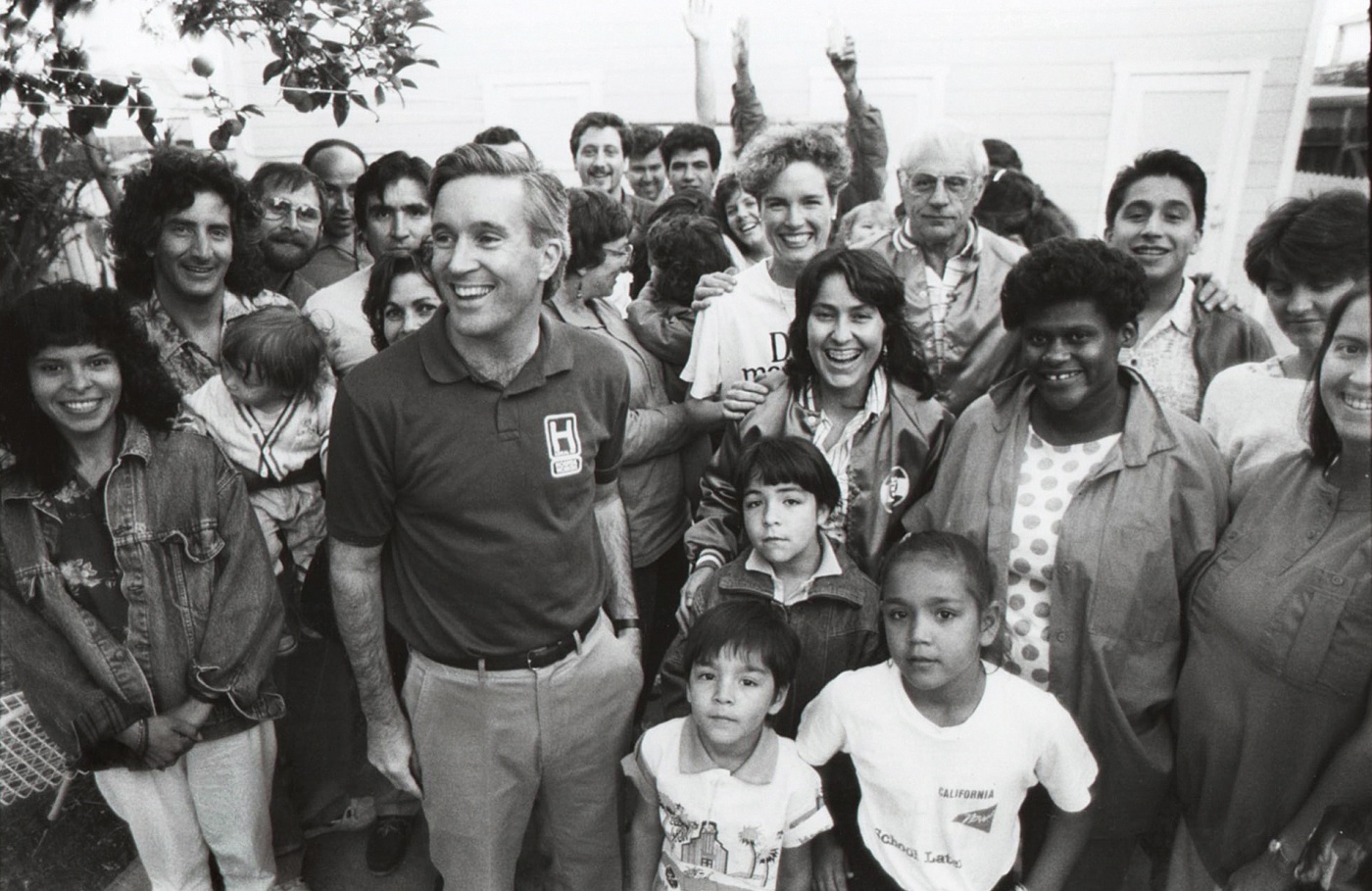

After graduation, Cecile Richards first landed in New Orleans, where she was part of a small effort to try—without much success—to organize workers in the highly seasonal hospitality industry, and where she met Adams, who was also on the campaign. Back in the day, access to health care for these workers was a pipe dream, but the problems of sexual harassment and other workplace abuse was already on the radar. Housekeepers knew to work with the hotel room doors open, and which customers to avoid. By really listening to the people she was working with—a skill that Adams said she carried with her all the way to Planned Parenthood—she learned that reliable, steady wages and respect at work were their top priorities.

Other organizing jobs followed, as well as stints working on her mother’s two campaigns for Texas governor. The first, against a Republican oilman named Clayton Williams, whom Richards described in her book as a “classic sexist pig” who “loved to make crude comments about women” and tried to intimidate her mother by getting into her personal space (“Sound familiar?” Cecile Richards wrote), was successful, leading to her becoming the governor in 1991. The second, as Texas was embarking on a noticeable rightward shift and after Richards vetoed a concealed carry gun bill, was not; the victor that year, 1994, was future president George W. Bush, the son of the man she had so effectively mocked six years earlier.

Cecile Richards and Adams were also starting their family during that period. Their three kids were raised the same way Richards was, always in the fight, and all three are still politically active; their two daughters, Lily and Hannah, worked on the Clinton campaign, and Daniel is pursuing a doctorate in chemistry and also actively backed Clinton.

She later went to work for Nancy Pelosi, a woman of her mother’s generation who did what Ann Richards had done: married, raised kids, then embarked on a landmark career of her own. After that, Richards founded and ran a progressive nonprofit called America Votes.

But despite the long resume, when Planned Parenthood came calling in the mid-2000s Richards had a crisis of confidence and almost skipped the interview. At the Nashville event, when Patchett noted many in the audience could probably relate, Richards acknowledged how common it is for even accomplished women to doubt themselves. She said she did what many people do when they need guidance: she called her mother.

“She said ‘Cecile, get over yourself. This is the only life you have. You will regret it forever if you don’t try,’” recalled Richards. “I think she was always frustrated she spent many of her years raising kids, making dinner, running carpool. She was wildly impatient at every woman who didn’t just jump at every chance they had.

“We tend to step back and wait for someone to say, ‘Okay, you’re ready now,’” Cecile Richards continued, launching into another life lesson she learned along the way. “So that’s my new motto. Start before you’re ready.”

In the public eye

Start she did in 2006, and her tumultuous years at the helm of Planned Parenthood, which celebrated its centennial last year, saw momentous highs and frustrating lows.

On the political front, the organization played a major role in not just passing the Affordable Care Act but making sure that it included no-cost birth control of all sorts. Richards always links that policy to the drop in teen pregnancy and abortion rates, both of which have hit historic lows in recent years. (As she told Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, according to her book: “We are actually making enormous progress for women’s health. And if we could just take politics out of the equation, we could keep making progress.”)

Realizing that basic health information was a precious commodity, Richards oversaw a revamp of the group’s website to make it a full, reliable resource on topics from different types of birth control to sexual consent, and from sexually transmitted diseases to gender identity. Last year, she said, the site got 99 million hits.

Richards also worked to bring young people into the fold as educators and in other roles. It’s a natural fit, she said, because they’re already interested in sexual health and sexual identity. Richards said the group’s number of supporters—it defines them as people who have given money, signed a petition or had some other interaction with Planned Parenthood—went from 3 million to 12 million. More than 2 million of those supporters have signed up since the 2016 election, according to Planned Parenthood figures.

There’ve been huge controversies, too. One was when the Susan G. Komen breast cancer advocacy foundation severed ties with Planned Parenthood, which conducts breast exams and refers patients who need additional care, in 2012. The stated rationale was a new policy prohibiting the foundation from funding any group under government investigation, and Planned Parenthood at the time was under investigation by an anti-abortion congressman who said he wanted to know if it spent public money for abortions. But many believed that the investigation was for show and that Komen officials were bowing to political pressure. The foundation ultimately reversed its position after Richards and her staff “asked our supporters to stand with us. Boy, did they,” she wrote.

Another controversy: The damning, heavily edited videos recorded by abortion opponents that purported to show that Planned Parenthood sold fetal tissue. After they were released, Richards was called before the House Oversight Committee, one of four committees investigating the group. She gave an epically cool-headed performance, at one point leaving chairman Jason Chaffetz stammering after he demanded she explain a chart he claimed came from Planned Parenthood–and Richards calmly pointed out that it was actually produced by an anti-abortion group.

She was nervous before the hearing, but in hindsight, she said, all they wanted to do was get her mad, “and the more I don’t take the bait, the more the veins are popping out of their foreheads.”

Vice President Mike Pence has been a recurring character in this story. Back when he was still in Congress, he was one of the leading voices for defunding Planned Parenthood. Richards actually tracked down Laguens, Planned Parenthood’s current executive V.P., on Christmas Day after the 2010 elections to recruit her from a consulting job to fight the Pence amendment, which proposed not only cutting off Planned Parenthood but eliminating an entire $300 million program to provide aid to low income women for reproductive health and family planning. The measure passed in the Republican-controlled House and failed in the majority Democratic Senate. After he reemerged as Trump’s vice president, Planned Parenthood supporters launched a cheeky campaign to donate to Planned Parenthood in Pence’s name. In fact, assaults against the organization and its mission have often created groundswells of support, which Richards and her staff have skillfully leveraged.

The political attacks serve to “remind people of how important Planned Parenthood is,” Richards said. “We’ve used that to elevate people’s understanding. That’s what I think building a movement is all about.” Or, as she put it in Nashville: “If the idea is to make lemonade out of lemons, we’re a lemonade factory.”

What next?

Richards signed off at Planned Parenthood last spring, just as her book tour was starting. She told CBS News that “it’s hard to leave, but I’m ready to step aside and have someone else take on the responsibilities at a time where I think we’re incredibly strong in this country.”

What comes after this is up in the air. She receives frequent, sometimes colorful pleas to follow in her mother’s footsteps and run for public office—a written question to that effect at the Nashville book event ended with “please, pretty please run, dammit.” She says it’s unlikely, but she also doesn’t rule it out.

For now, she’s working to fight Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation and is quick to rattle off what’s at stake: 401 new laws limiting abortion passed since 2011 in 33 states, all designed to “shame, pressure, and punish women,” and 20 states that would immediately seek to ban the procedure outright should Roe v. Wade be overturned.

“So you better believe I’m going to be traveling the country doing everything I can to spread the word and mobilize people,” she said.

She’s also zeroing in on the fall elections, particularly getting women to vote and making sure that, after election day, attention remains focused on the issues those voters care about.

She’s focused on making sure the surge of involvement that has her so heartened doesn’t fade, even if change doesn’t come quickly, or easily. She believes Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice”—justice, in her view, including full reproductive options for women. But “the arc doesn’t bend itself,” she observes. “It requires massive movements of people who believe the world can be better, and who take an active part.”

That’s a lesson she said she learned from her mother, who died of cancer in 2006, who understood that “these men have had things pretty good for a long, long time, and they’re not going to give up any of this power without a fight.”

It’s also one she internalized from decades of fighting for longshot causes, often with disappointing results—at least at first. Not that long before the Affordable Care Act made no-cost access to birth control the law of the land, she said, birth control proponents were still fighting to get pharmacies to fill prescriptions. And Brown didn’t divest from South Africa while she was a student, but in 2010, both Richards and Nelson Mandela were awarded honorary degrees.

“You never know,” Richards says, “where the tipping point will be.”

Contributing Editor Stephanie Grace is a political columnist for the New Orleans Advocate.