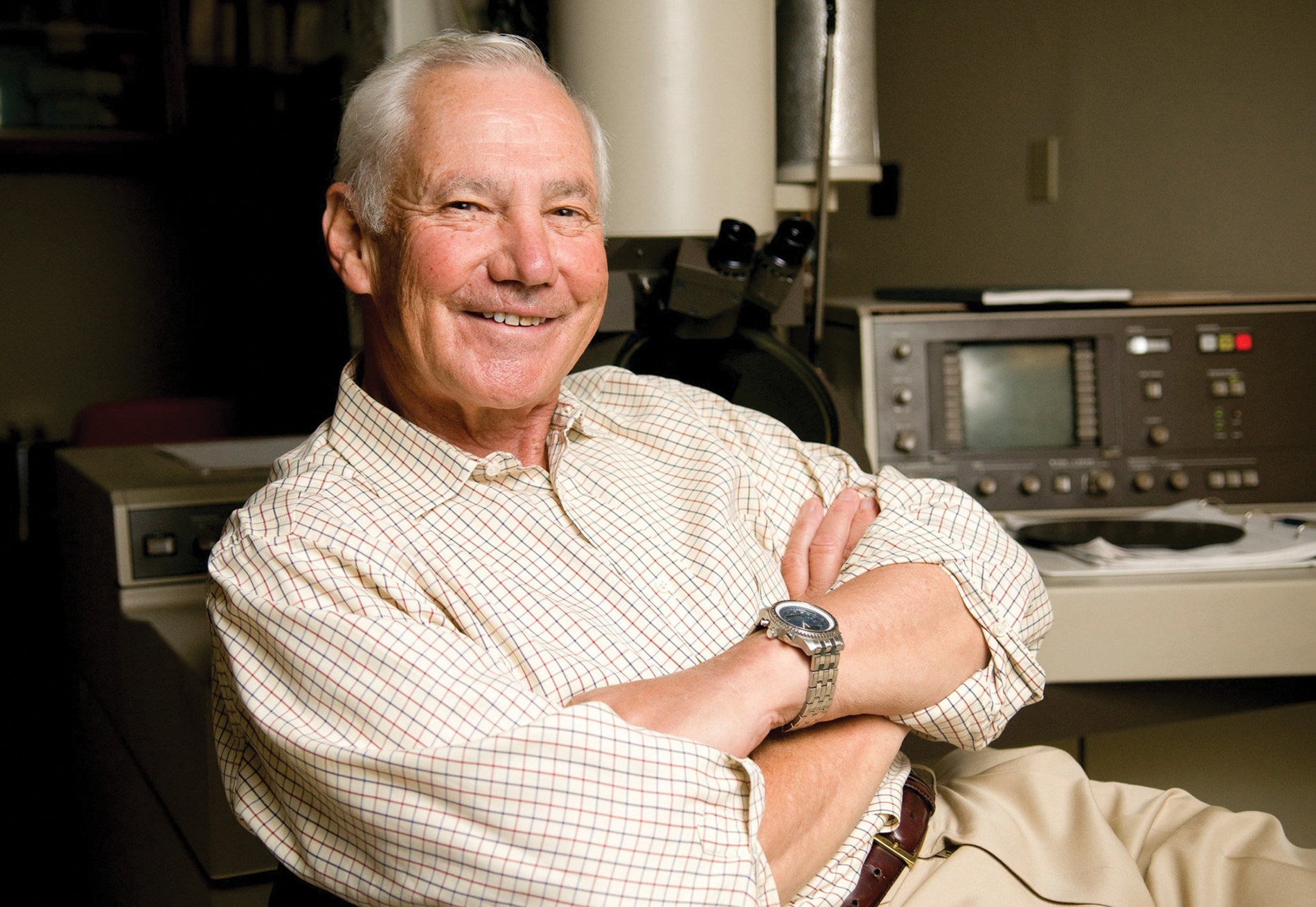

Stanley Falkow PhD ’61 was “one of the great microbe hunters of all time”—or so he was dubbed as he was presented the 2008 Lasker-Koshland Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science, nicknamed the “American Nobel.” Brown President Christina Paxson gave a slightly more academic description of him as she awarded him an Honorary Doctor of Science Degree (Sc.D.) in 2013, calling him “the father of molecular bacterial pathogenesis,” which is the study of how infectious microbes cause human disease. The widely celebrated Stanford professor researched illnesses as varied as diarrhea, plague, gonorrhea, and whooping cough, but he was best known for discovering how antibiotic resistance spreads from one bacterium to another. Peter Shank, professor emeritus of medical science and adjunct professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, remembered Falkow as “both a wonderful scientist and a warm and caring person.” Shank hosted him in 1988, when Falkow gave Brown’s prestigious 22nd annual Charles A. Stuart lecture (named for Falkow’s own mentor), an honor that places him among a slew of Nobel Prize winners.

While Falkow himself did not win the Nobel Prize, he was nominated for it—and won many (if not all) other major science awards. In addition to the “American Nobel,” he also won the 2014 National Medal of Science, given by President Barack Obama in a ceremony at the White House. Falkow considered his 2007 induction into the Royal Society in Britain, where he joined the company of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, and Albert Einstein, as one of his foremost honors.

PASTEUR AND SAUERKRAUT

Stanley Falkow was born in Albany, New York, in 1934 to two Yiddish-speakers: a Soviet immigrant shoe salesman and the daughter of Polish immigrants, who ran a corset shop. The family moved to Newport, Rhode Island, in 1943. Although his was not a big reading household and he was a poor student with weak eyesight, Falkow said that his passion for bacteriology started with a library book: “At the age of 11, I read Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters, which dramatized the discovery of bacteria and viruses and their roles in human disease,” he wrote in the article “I Never Met a Microbe I Didn’t Like,” published in the journal Nature Medicine in 2008.

The book’s heroes included Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch—and they became Falkow’s heroes. “I dreamed of becoming a bacteriologist,” he wrote in the same article. His first view of bacteria was in spoiled milk: “barely discernible in my [...] microscope, but no doubt about it, here were Antony van Leeuwenhoek’s tumbling animalcules.”

In 1951 Falkow enrolled at the University of Maine, where his early training as a bacteriologist included making sauerkraut in a lab: “[We] studied how each group of microbes interacted and sequentially cooperated to transform a crock of alternating layers of shredded cabbage, salt, and water into a wonderful accompaniment for bratwursts,” he recalled in a 2008 article, “The Fortunate Professor.”

After graduating in 1955, he began graduate school at the University of Michigan, but recurrent bouts of anxiety and agoraphobia compelled him to drop out. Falkow learned to manage his panic attacks, using tactics as varied as fly fishing and, thanks to the recurring subject of his bacteriological research, scatological humor.

“Shit is often funny,” he wrote in a 2014 article, “On Teaching.” (He was once gifted with a framed collection of fake feces, which he proudly displayed in his office.) Lecturing made him anxious—but he found that making people laugh relaxed him. “I confess the belief that microbes will always have the last laugh,” Falkow once wrote, but he laughed along with them.

TRANSPLANT PIONEER

Falkow resumed graduate school in 1957 when he began his studies at Brown, during what he referred to as “The Golden Age of Molecular Biology.” He researched in Charles Stuart’s lab, worked as a teaching assistant for Seymour Lederberg, and took classes from Elizabeth LeDuc, whose cell biology lectures, he once recalled, “seemed like poetry.” In “The Fortunate Professor,” Falkow reflected on his time at Brown: “All my professors […] led my classmates and me to the cutting edge of thinking about the biology of that era. They posed questions I had never contemplated, and, now forced to consider them, I was humbled and yet challenged. Graduate school was one of the happiest times of my professional life.”

During that period, Falkow also performed early fecal transplant experiments—a currently revived technique that shows great curative promise—working to mitigate the harsh effects of antibiotics by giving patients capsules of their own healthy stool.

For a 2014 New Yorker article, “The Excrement Experiment,” Falkow recalled being confronted by a hospital administrator in 1958—“Is it true that you’ve been feeding the patients shit?”—and getting fired on the spot.

After earning his PhD in 1961, Falkow did postdoctoral research at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Maryland, and taught at Georgetown and the University of Washington, before his 1981 arrival at Stanford, where he worked until his 2010 retirement.

“He was one of those rare people who truly did live for and embody the joy of science,” says David Relman, a colleague and former student of Falkow. “He loved science for the beauty of it, for the intrigue, for the fun.”

Falkow died on May 5 at his home in Portola Valley, California. The cause was complications of myelodysplastic syndrome, a bone-marrow disorder. He was 84. He is survived by his daughters, Jill Stuart Brooks and Lynn Falkow Short; and by his wife, Lucy Tompkins, also a professor at Stanford, where Falkow was professor of microbiology and immunology at the School of Medicine for nearly two decades.