Why does Brown have so few military veterans? Many institutions have far more. In seeking answers, I came across journalist Wick Sloane’s annual survey of highly selective institutions for Inside Higher Ed. Turns out the percentage of veteran undergrads here—0.3—isn’t too different from other Ivies, and is higher than Yale’s, where there were just 12 last year; Harvard, with six; and Princeton, with five. In all, at 36 top schools, there were just 722 undergrad vets.

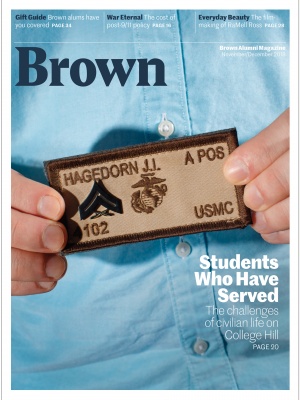

Brown leaders say they want to do more. Enrollment is up, and Brown is one of the few in the Ivy League to offer a dedicated liaison for veterans on campus. That’s important because veterans’ lives are often far different from those of other undergrads. In our feature on student vets, starting on page 20, you’ll see that our subjects were all photographed at home. Often older than traditional students, perhaps married or juggling other obligations, veterans may spend less time on campus than their classmates. We wanted to meet them where they were.

Many of Brown’s post-military students are veterans of the U.S. war on terror; in fact, two of the veterans you’ll meet in our story were inspired to further their educations because of experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan. In his new book, The Oath and The Office: A Guide to the Constitution for Future Presidents, reviewed on page 14, political science professor Corey Brettschneider looks at the war on terror with a constitutional historian’s eye. It’s now 17 years since Congress approved U.S. military action, originally against Al-Qaeda, and there’s no clear endpoint and an ever widening theater of engagement. Brettschneider decries what he sees as Congress’s delegation of its heavy burden of wartime decision-making to a succession of presidents and argues it should pass a new war powers bill, giving the responsibility to wage war—or not—back to the legislature.

The Watson Institute Costs of War Project also investigates the ways the war on terror is different from previous conflicts, and comes to some startling conclusions. Political scientist Rosella Cappella Zielinski examined funding for U.S. military action since the War of 1812 concluding that the borrowing of the current era will cement financial inequality as wealth is transferred from the citizens who service the debt to the individuals who hold it. As you’ll read on page 16, it’ll be quite a price tag: $5.6 trillion. That’s more than three times the Pentagon’s current estimates. One key expense the Pentagon doesn’t factor in, but this project does: future healthcare costs for veterans.

A beautiful photo from this year’s gift guide almost graced this issue’s front cover. Readers tell us they love the guide, and we love how many of you we hear from when we put it together each year. But we wondered: Are glossy consumer images who we are? So our cover reflects the changing life of a former Marine, because that felt important, and because as these stories show, we’re part of a community that values education and scholarship not as abstract values, but as tools to examine the things that matter.