Tuning Up

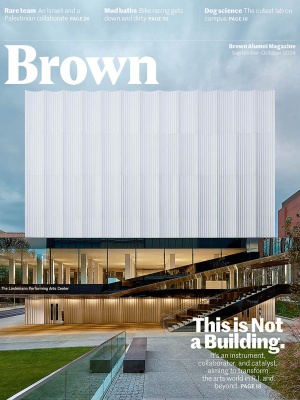

As the new, high-tech Lindemann Performing Arts Center turns one, artists are just starting to take advantage of all it can do.

“The building is an instrument and we’re learning to play it,” says University Architect Craig Barton ’78 of Brown’s new Lindemann Performing Arts Center, which opened last fall and is arguably the most technologically advanced theater in the world—and at 60 feet below ground level, literally the most deeply rooted building in Rhode Island. Already, the high-tech marvel has become one of the most vibrant arts collaboratives in the Providence community.

The Lindemann’s mainstage offers at least five performance spaces in one, with the walls, floors, and lighting grids able to rearrange themselves to the needs of the production in an unprecedented way. Barton isn’t being metaphorical in using the word instrument: Last summer featured “tuning” sessions as sound engineers perfected the acoustics of the various configurations. The building itself is designed to be integral to the creative process, explains principal architect Joshua Ramus, founder of the New York City–based firm REX, known for his work on the Wyly Theatre in Dallas, Texas, and the Perelman Performing Arts Center in Manhattan. It needed to “be a catalyst and an instigator and have a personality. It needed to open possibilities, not limit them,” he says.

That the design was intended to encourage artistic experimentation is evident in its three

below-ground rehearsal rooms that are set up to allow artists to rehearse and perform simultaneously. Each transforms into a performance space, including one room that doubles as a black box theater, another that has the capacity to seat an audience of 135 and boasts floor-length curtains that provide acoustic dampening, and a third that provides a spacious sprung floor to accommodate dance performances. All of the rooms are equipped with state-of-the art soundproofing construction and materials that mean more than one performance can occur at the same time.

“When you match the building’s revelations with the Open Curriculum and Brown’s approach to crafting your own academic vision, giving people agency in what they want to do, you get this really beautiful, unexpected combination,” says Artistic Director Avery Willis Hoffman, who arrived at Brown in 2019 when the building’s infrastructure had already been towering over the neighboring Granoff Arts Center for over a year. As a producer, Hoffman, a niece of Toni Morrison, has created a wide range of cultural events, including her most recent multi-partner digital event 100 Years/100 Women (2020), which Vogue magazine dubbed both “urgent” and “rich.”

The collaborative, multidisciplinary planning process for the Lindemann was very Brown, as well: The complex and diverse needs that the venue would ultimately have to fulfill as a multi-genre performance space took weeks of “dreaming,” and the design team met weekly with students and faculty and artists and administrators, all of whom brought a myriad of visions to the table. “The fact that Brown committed to the cost impact of getting everyone together on a weekly basis was phenomenal,” says REX Project Manager Adam Chizmar. “Maybe even made it possible.”

“On this building there were two ideas,” says Ramus. “One was this extraordinarily transformable high-performance main hall that would be exceptional for orchestra, for recital, for theater, for dance, for media—which is a new animal. And then there’s that glass clerestory that cuts through the building, the whole intent of which was to allow the contents to bleed out and for the University to invade.”

Barton, a semiotics concentrator who has walked Brown’s paths for decades, speaks poetically about the “porosity” of the campus, the way it is built into the larger Providence community, without the gates and brick walls of the other Ivies. In particular, he loves the way the Lindemann’s glass “bridge” allows passersby to feel one with what’s happening inside the institution.

Back to the future

To ensure the safe movement of the seating, glass walls, balconies, flooring and the sail-like acoustic reflector panels (ARPs) anchored end-to-end across the ceiling, Ramus relied on decidedly un-technological solutions. “The ARPs are controlled by the same pulley system that zooms cameras around in stadiums. When was the last time you heard about one of those flying into the crowd?” Meaning, of course, that while the Lindemann is physically one of the most transformative theater spaces in the world, it is also one of the safest.

Looking upward in the main hall, it’s also easy to see that the building’s functional components are held in place and moved on what looks to be an old train track—right out of the 1890s. “Because the gantries are moving, for instance, we had to be able to create these drawbridges that continue the egress routes,” says Ramus. “We could have invented them or we could just use the drawbridges that are on the back of fire trucks.”

In Ramus’s cutting-edge design, the main floor of the Lindemann sits above street

level and the seats in the building’s small amphitheater take on the appearance of gentle waves to visitors climbing the building’s steps or entering the elevator. The main floor and lobby of the building is distinguished by its glass perimeter, the transparency allowing visitors to make peace with the rather dramatic rise and girth of its fluted, almost gill-like aluminum siding, masking an inner layer of porous material that “breathes” to protect the building from the rot and deterioration all too common in New England. About the siding, Chizmar says, “Basically, we knew we had a big blank [exterior] surface area that didn’t want or need apertures in it, so we needed something that had depth to gently echo the traditional structures in the neighborhood without using the same materiality or design language.” Meaning no brick and white pillars. As far as being green, says Ramus, that’s a given in any building being constructed under his watch.

“Then there’s that glass clerestory that cuts through the building, [intended] to allow the contents to bleed out and for the University to invade.”

When the Lindemann finally opened last fall, made possible by a generous grant from longtime University benefactors Frayda Lindemann and her late husband George Lindemann Sr., the 1,000-strong crowd that convened on the October morning stood in lines that wound around the corner and up Angell Street—despite the National Weather Service issuing a flood watch. But then persistence, that Yankee virtue, has always been a key player in this building’s history. The 101,000 square foot structure required ten years of planning, five years of construction, and even the moving of a historic house that was its own technological feat (see BAM’s 2019 story “Wheel House”).

Reinventing Brown theater

“The challenge” with staging productions at the Lindemann, says Senior Technical Director Shawn Tavares, “comes in getting people to wrap their head around the level of flexibility we have. It’s not the technology—it’s the way it’s applied.” The team is working to encourage creators to move toward producing art that incorporates what the Lindemann can do, rather than just presenting performances that were worked out elsewhere. “Being in the building definitely affected my programmatic vision,” says Hoffman.

Another priority for the center is to deepen Brown’s ties to the Providence arts community. “The Lindemann is a critical component of Brown’s mission moving forward, as historically, Brown has not always been accessible to the outside community at all,” says artist, poet, and songwriter Chachi Carvalho, one of the six IGNITE artists presented this year as well as a member of the 40+ Artistic Innovators Collective. Carvalho was invited to conduct a private tuning event in the summer of 2023, to test the acoustic viability of the theater as it morphed from intimate black box theater into 500-seat orchestral hall and beyond. “Starting an arts institute at this time is a gift,” says Hoffman, “because there’s a real reckoning, a real call for equity, inclusion, and diversity in all the ways that we define diversity, not just race or gender.” With the Lindemann, those values were built in from the beginning.

Carvalho’s Local Traffic is one of four extended works featured as part of IGNITE, the Brown Arts Institute’s multi-year series of “creative activations, interventions, and investigations” that have manifested as residencies, lectures, and exhibitions throughout the center’s first year. The inclusivity isn’t limited to artists: Carvalho also created the Labor of Love event in the fall to honor all those who worked on the actual construction of the Lindemann. Carvalho, a first-generation Cape Verdean–American who is also the first chief equity officer for the City of Pawtucket, believes this inclusivity will build on itself and further draw the community into the process of art making and arts education.

“The challenge [with staging things at the Lindemann] comes in getting people to wrap their head around the level of flexibility we have.”

There’s also a workforce-training aspect to the Lindemann and its complexities in the Brown Art Institute’s initiative, ArtsCrew. Members, whether seasoned professionals or students making their first foray into the space, will receive training where necessary and be paid for their work. “If anything, you need more people when you’re moving a

many-tonned piece of glass around,” says Tavares.

“My goal with this whole experience is to be able to create a bridge from the outside community into Brown and give them an opportunity to see what resources are there and available to them,” Carvalho says.

So far, the programming at the Lindemann, including appearances by such world-

renowned performers as Itzhak Perlman, Carrie Mae Weems, William Kentridge, and many others, alongside student performances by the Brown Symphony Orchestra and the Brown RISD student group, is already accomplishing this bridge-building tenfold.

With additional collaborations with the Rhode Island School of Design and the Trinity Repertory Company already in progress, and others that are drawing on at least seven other disciplines at Brown, Hoffman is taking center stage in realizing President Christina H. Paxson’s commitment to making the University an arts “laboratory,” one that will be the first choice for prospective students interested in a fully integrated arts program.

Hoffman loves the idea that the work on display at the Lindemann might also be messy and unbounded in the best possible sense and stresses the importance of failure in the creative process: “There’s so much pressure to have it all worked out. Failures are much more interesting. Being able to encourage people to positively fail and to experiment and innovate and incubate—these are all the kinds of words that we’ve been using.”

Of learning to play the Lindemann? “It’s easy to forget how cool this space is,” says Tavares. “And then we do a public event and see the people’s reactions and we’re reminded that what we’re doing is really exciting.”

Carvalho says the Lindemann has made a big impact on his sense of himself as an artist and on his relationship to Brown, and hopes others in the extended Providence and Rhode Island community will feel the same: “Being asked to teach a master class on songwriting to students, faculty, and community members at the most prestigious university on the globe made me say ‘Wow—if these folks are looking at me in this light, why am I not looking at myself in that light as well?’” A devoted father, he’s made it clear to his four children that they are all now “a part of the Brown family. We belong here.”

Julie Batten, a visual artist as well as a writer, loves living and creating in Rhode Island.