Moon Madness

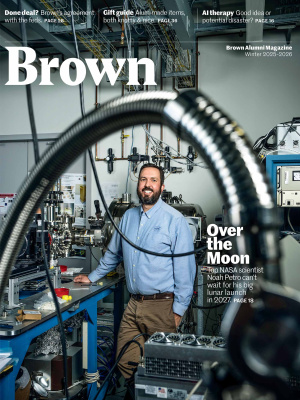

Noah Petro ’03 ScM, ’07 PhD, has long been obsessed with all things lunar. Now he’s the lead scientist planning the first footprints on the Moon in the 21st century.

“We’re going to the Moon!” says Noah Petro ’03 ScM, ’07 PhD, with a wide smile.

And he means it—literally. Petro is the project scientist for Artemis 3, scheduled to launch in mid-2027, which will send humans to walk on the Moon’s surface, near the lunar South Pole. This will be the first time humans set foot on the Moon since a total of 12 Americans did so between the first Apollo 11 landing in 1969 and the Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 landings in 1972 (see sidebar on p.22).

The Moon’s South Pole, where the Artemis missions will land, is a completely different—and much older—environment than the smoother lava-coated terrain the Apollo astronauts landed on more than 50 years ago. The polar environment offers access to some of the Moon’s oldest rocks, including ones nestled in shadowy regions that may contain frozen water and other useful compounds.

“Artemis is envisioned as not just a few one-off missions,” Petro explains, “but a longer-scale program where we’re building the ability to stay there for extended periods of time. When we go to the South Pole, we’ll learn about rocks that were formed 4 billion years ago, and then what’s happened in the subsequent 4 billion years: other impact cratering, solar wind interactions, galactic cosmic ray interactions. There’s a whole history that’s written in those rocks that’s far older than almost any rocks on Earth. We can use those places to help understand what’s happened to the Solar System over four billion years. What a lofty question!”

“We can use those places [at the South Pole] to help understand what’s happened to the Solar System over four billion years. What a lofty question!”

While NASA funding continues to be in flux in a shifting federal funding landscape, a late amendment to the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” secured $9.9 billion for NASA infrastructure and human spaceflight, including support for Artemis and its flight hardware over the coming years.

A New Generation of Astronauts

For anyone born after 1972, “this is the first time in our lifetimes that anyone will walk on the Moon,” Petro says. Of the 12 humans who’ve walked it, virtually all are either retired or deceased.

“We’re in different times, using different systems, different training, different everything, so we have to forge some new ground,” Petro says. Whereas the Apollo computers had less processing power than a modern graphing calculator, the Artemis hardware will include state-of-the-art equipment from NASA and from SpaceX and Blue Origin, the private space companies founded by Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, respectively.

Likewise, Apollo crew members wore spacesuits so stiff and awkward that some astronauts, in the low-gravity environment where rocks almost seemed to float, found it easier to kick up a rock and grab it than bend down to pick it up. Artemis spacesuits, by contrast, feature dramatically enhanced mobility and protection from potential hazards, as well as cutting-edge communications technology.

Similarly, the spider-legged Apollo lunar landers were left behind at the six landing sites (and remain there today), but the Artemis lander—formally, the SpaceX Starship Human Landing System—is a massive, reusable cylindrical rocket that is expected to land and re-launch from the lunar surface over and over again in the coming decade.

“Starship is this amazing, gigantic rocket,” Petro says. “Astronauts will ride an elevator down to the surface. They’ll have at least six days on the surface, probably four moonwalks, then everything launches back into space.”

In addition to transporting humans and their living quarters, NASA plans for uncrewed Starship trips to transport equipment to the lunar surface to help build a permanent lunar research and mining facility—not exactly the “Moon colony” that science fiction authors imagined a generation ago, but a science and engineering hotspot from which future Mars missions can launch without having to fight Earth’s much higher gravity.

Artemis 1 launched without a crew in November 2022 to test the equipment, especially the new Orion heat shield. Artemis 2 is slated to launch in April 2026 and carry four astronauts around the Moon and back again, but Artemis 3 is the first of this new generation of Moon missions where astronauts will actually walk on the Moon’s surface. Artemis 4 and 5 are slated to visit other areas near the South Pole to gather different samples and piece together a more comprehensive picture of the materials and minerals there that could be of benefit to future space missions (as well as humans back on Earth).

At the moment, nine sites are in final contention to be the landing zones—all within about 150 miles of the South Pole.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve just loved the Moon, just reading and talking and thinking about it.”

Longtime Lunar Lover

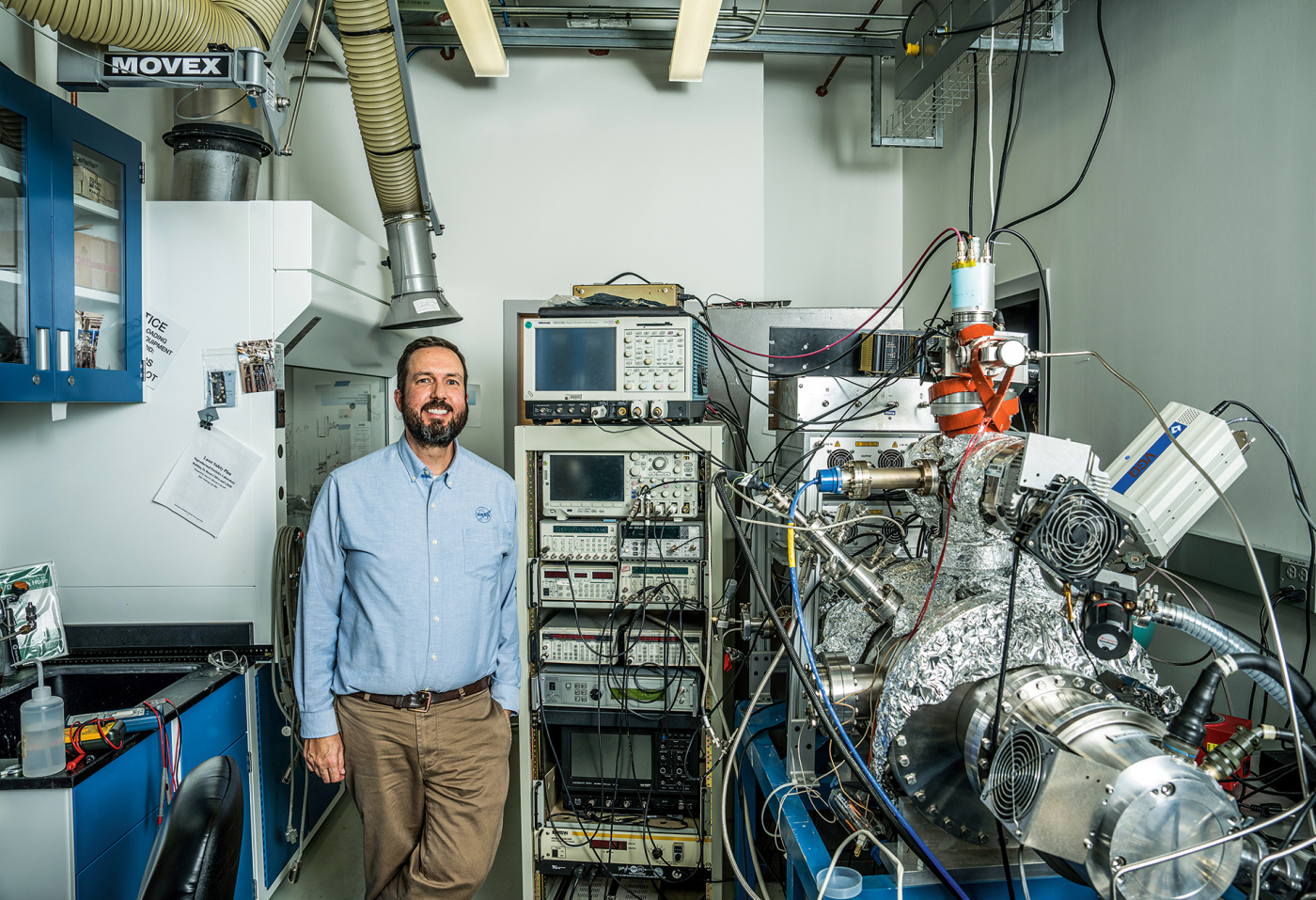

Petro is plenty qualified to lead this undertaking: After finishing his PhD in geological sciences at Brown in 2007, he headed straight to the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center for a lunar science postdoc—and never left. He soon joined the Goddard team working on—and, by now, leading—the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), a remarkable mission that launched in 2009 and is still producing extraordinary data detailing the geography, geology, and chemistry of the Moon.

But Petro is also simply a Moon junkie, having spent most of his free time since childhood obsessed with it.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve just loved the Moon,” he says. “Reading history books and watching documentaries, just reading and talking and thinking about it. I’m so fortunate that I get to work in a discipline where my bizarre knowledge base is useful.”

Says Sarah Noble ’00 ScM, ’04 PhD, who, as the lunar science head at NASA headquarters, works with Petro daily: “It’s super handy to have him around. He’s like a walking Apollo encyclopedia. Whenever we have questions like, ‘How far did they walk on Apollo 14?’, he can just rattle it off.”

As a child, Petro learned that his father had helped design the Apollo spacesuits—and hence felt personally tied to the historic missions. As an undergrad at Bates College, he discovered planetary geology and started evolving from a passionate Apollo hobbyist into a lunar scientist.

New Data, New Questions

At Brown, Petro focused on the South Pole–Aitken Basin, a truly gigantic impact crater on the back side of the Moon that is one of the oldest features in the Solar System, dating back about 4.5 billion years.

“South Pole–Aitken Basin has been one of the top lunar science priorities for almost 30 years now,” he says. In those years, “we’ve collected remotely sensed data and we have more models, but we don’t have any more answers. It’s still as curious and captivating as it was 20 years ago.”

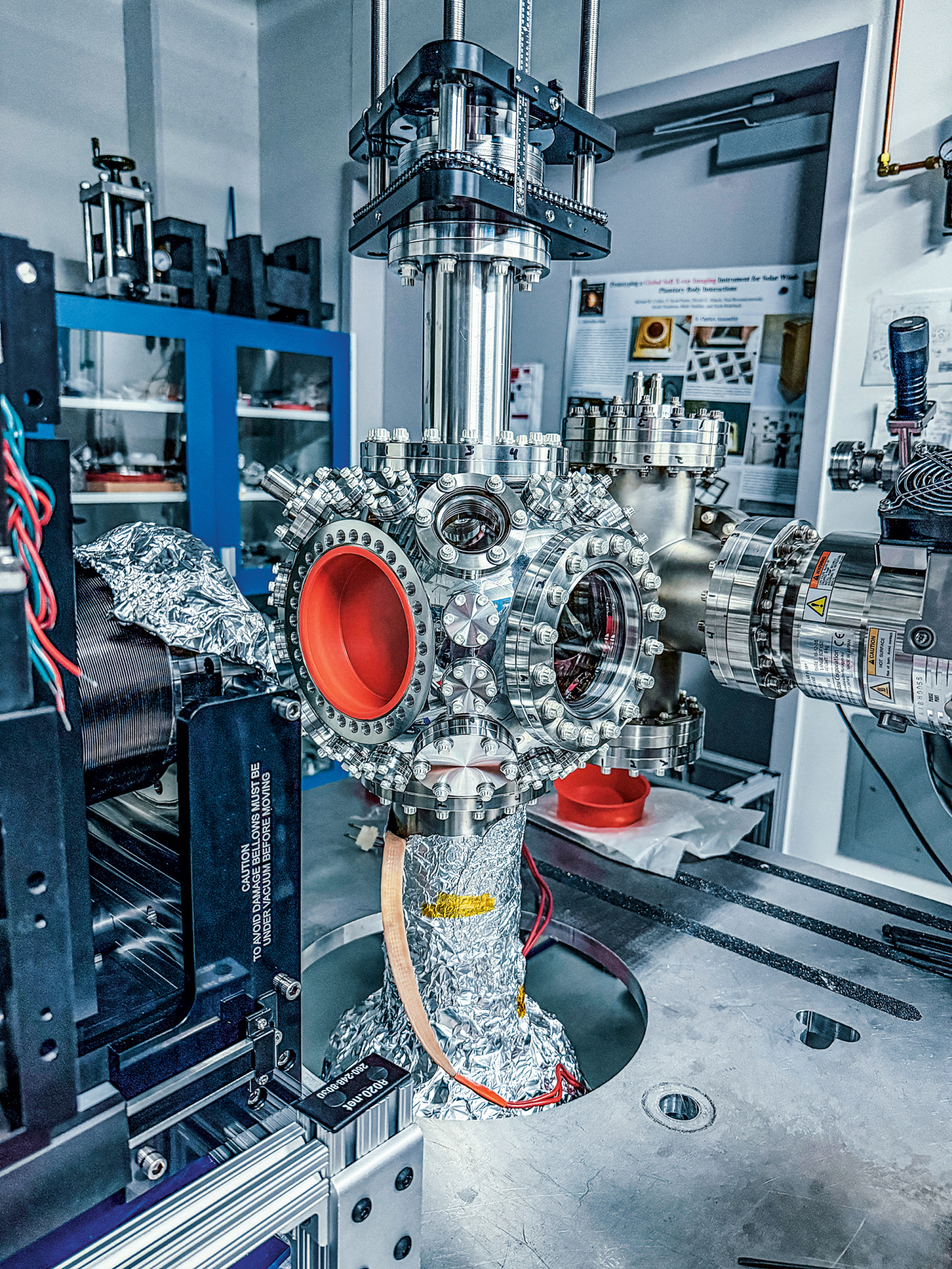

Indeed, that new data—from LRO primarily but also from a raft of Chinese Moon missions—has raised newer and equally fascinating questions, including about the presence of hydrogen and oxygen near the South Pole, and the existence of lunar granites—rare, silica-rich igneous rocks—which previous models of the Moon would argue shouldn’t exist.

Sending humans to gather rocks from these areas will equip planetary geologists to tackle these questions. “We may not get all of the answers we want, but we’ll get some,” says Petro.

He and his NASA colleagues have already begun training the astronaut corps and NASA staffers in lunar geology—and he swears he’s not biasing them in favor of his favorite impact crater. “We have so many unknowns, and we just have to put ourselves in a position to collect samples to just begin to chip away at these questions,” he says.

Artemis 3 will be a discovery mission, and Petro says he’s as eager to find new mysteries as to find answers to existing questions. “LRO has taught us that we don’t know as much about the Moon as we thought we did. And that’s exciting, because that’s what science is. I’m totally excited to stand before a room filled with planetary scientists in 2026 or 2027 and say, ‘We got this right, and boy, we got these things wrong. And here’s how we’re going to do things differently and better.’”

While at Bates, Noah applied to work with Brown’s Carle Pieters, now professor emerita of earth, environmental, and planetary sciences (see sidebar). Her own planetary science career had begun with organizing hundreds of photographs taken by Apollo 11 and 12 astronauts, in the immediate aftermath of the mission.

What began as an essentially clerical task grew into a wealth of science discovery as Carle began noticing patterns and features in the images. In time, Carle became a world leader in studying lunar volatiles, the scientific term for compounds and elements like hydrogen (H) and carbon dioxide (CO2) that prefer a gaseous state over being a solid or liquid.

Water on the Moon?

Hydrogen and oxygen are a big part of the reason that NASA identified the Moon’s South Pole as its destination for the forthcoming trip and still-theoretical lunar base. There is not yet proof of water ice under the lunar soil, but LRO spotted frost with hydrogen and oxygen in it, which suggests the strong possibility of water ice (H2O). Even if it’s only water’s less-useful cousin, a hydroxyl ion (OH), future residents of a permanent lunar base could use those constituents in many useful ways.

That’s the number one draw for NASA. “Location, location, location,” Petro jokes. “It’s just like real estate.” If Artemis astronauts do find large volumes of water ice, as expected, that means that future astronauts and lunar residents “won’t have to take all of our water with us.”

“We’ve collected data and we have more models, but we don’t have any more answers. It’s still as curious and captivating as it was 20 years ago.”

Once the Artemis missions have clarified exactly how much water there is and how accessible it is, Petro said, all kinds of things become possible. “We can break down the water that’s there into hydrogen and oxygen and make rocket fuel” to power future missions back to Earth or on to Mars. And depending on the water’s abundance and purity, “we can use it to cool systems, to drink, to water plants—what have you.”

A second vital resource available at the South Pole is the Sun, he says. Because the Moon has very little axis tilt, the Sun remains very low on the horizon all year long at the South Pole. That has two important implications. It means that many topographic lows are in eternal shadow, which makes them ideal areas for preserving ice. It also means that some topographic highs receive nearly constant light, which is great for harvesting solar energy.

Those permanently shadowed areas were one of the most startling discoveries of LRO. Launched in 2009, the orbiter was originally expected to last for only two years, but it’s still going strong. This Little Orbiter That Could has produced a wealth of remarkable lunar science, including the first and only topography map of the entire lunar surface, detailing the heights of every crater rim and deposit mare basalts (volcanic rocks that originate from partial melting of the lunar interior). LRO also took very high-resolution photos of almost the entire lunar surface, including the Apollo landing sites.

Not far from the permanently shadowed craters are those rocky highlands where the Sun shines most of the time, unlike the 50/50 sunlight-darkness split at the Apollo sites, which were all located near the Moon’s equator.

“That means that instead of having to survive fourteen and a half days in darkness, astronauts might have only a day or two in darkness before the Sun rises again,” Petro says. This guarantees enough sunlight to power solar panels at least 70 or 80 percent of the time, guaranteeing a deep well of power and a reduced need for batteries.

“So we have the volatiles resource, we have the solar resource, and then there’s the geologic context of the site on the rim of the South Pole–Aitken Basin, the oldest impact crater on the surface of the Moon, with its compelling scientific story of impact bombardment going back four and a half billion years, more or less,” says Petro in one breath. “I think it’s the intersection of those three things that drives us to the South Pole.”

What’s a Project Scientist?

An astronaut’s job description is an easy one: Go into space. As a NASA project scientist, Petro’s role is harder role to describe. Lori Glazer, head of planetary science at NASA, says it this way: “His job is to keep the science connected to the actual mission. As budget or time or other resources are constrained, he’s there to speak up for science and say, ‘You can’t do that because it’s going to compromise the science,’ or ‘Here’s a place where we can shave that off.’”

As a scientist, Petro is helping NASA pivot away from a space-station mentality, where spacewalks (extra-vehicular activities or “EVAs,” in NASA jargon) are more oriented towards building or repairing the International Space Station than doing discovery science. He explains: “Over the last 20 years, NASA has focused on operations where, when a crew member does an EVA, they’re heading to a specific piece of equipment.” Training, he said, has been, “You turn the bolt 15 degrees using three pounds of torque, no more, no less.”

But Artemis 3 will have to be different. “When Artemis astronauts take EVAs,” he says, “we can’t say, ‘Hit the rock five times, no more, no less.’ It’s an investigation. It’s exploration. We don’t know how many hammer blows it will take to dislodge a sample.”

Shifting NASA’s astronaut corps back to a discovery mindset is one of the deep joys for Petro of working on the Artemis missions. “Every human with sight can see the Moon,” he said. “If I got dropped into the middle of a different continent, with a different culture and no shared language, if I drew a picture of the Moon, that could be the beginning of communication.”

Science writer Liz Fuller-Wright ’03 ScM holds a master’s degree in planetary geoscience.

[ S I D E B A R ]

Brown in Orbit

A brief history of the University’s longtime relationship with space exploration

In 1967, Brown started a program in the nascent field of planetary geology, studying the geology of the Moon, Mars, and other terrestrial bodies. In the nearly 60 years since, Brown has become a leader in the field. Some highlights:

Advising Apollo 15/1971

Brown planetary geologist Jim Head works closely with the Apollo 15 astronauts on what Head calls “the first true scientific expedition to the Moon.” The expedition discovers green flecks on the lunar surface that turn out to be beads of volcanic glass. Later, in a Brown lab, geologist Alberto Saal shows that the flecks contain surprising amounts of water.

Leading Exploration on Mars/1981

The Viking 1 landing site on Mars is formally renamed the Thomas A. Mutch Memorial Station in honor of longtime Brown professor Thomas Mutch, a leading figure in the Viking program who had died climbing in the Himalayas the year before. The landing site was where the first successful long-duration landing on Mars occurred in July of 1976—with Mutch leading the imaging team.

Figuring Out What’s in Moon Rocks/2008

Carle Pieters (see sidebar, page 25), Brown professor emerita of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences, was the principal investigator on the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), an instrument that orbited the Moon aboard an Indian spacecraft.

Finding Water on the Moon/2009

Based on findings from the above-mentioned M3 instrument, Pieters and other Brown scientists announce the major discovery that the Moon has distinct signatures of water. Pieters says the findings prompt interesting new questions about where the water molecules come from and where they may be going—perhaps from non-polar regions of the Moon to its poles, where they are stored as ice in ultra-frigid pockets of craters that never see sunlight.

Telling NASA Where to Go/2021

After a seven-month, 300-million-mile journey, NASA’s Perseverance rover lands on Mars on February 18, to begin its search for signs of ancient life in Mars’ Jezero crater, which was home billions of years ago to a body of water about the size of Lake Tahoe. It was planetary scientists

at Brown who first put Jezero on the radar as a potential exploration site.

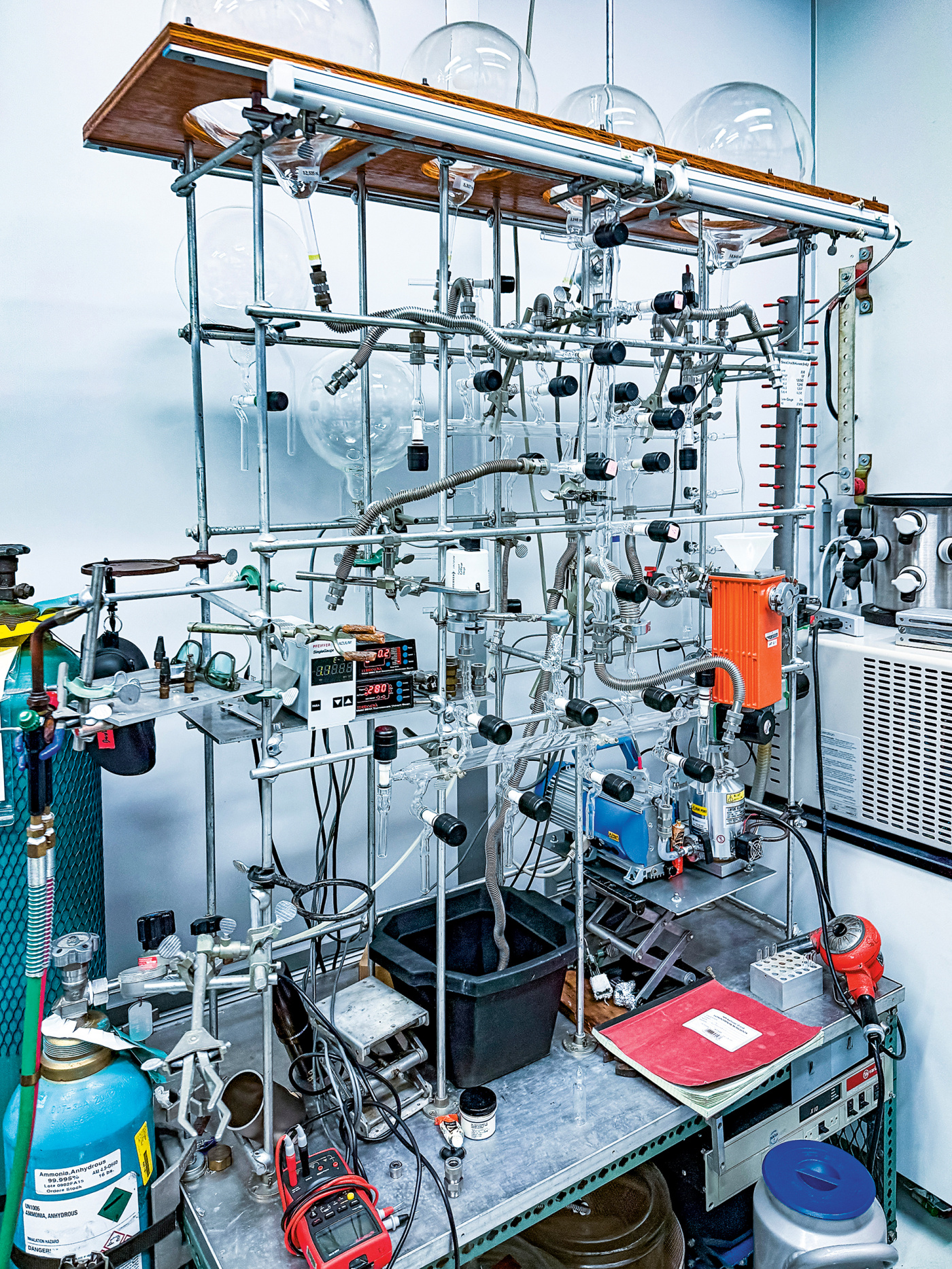

Analyzing Asteroids/2023

Samples of rock and dust from the asteroid Bennu begin arriving for analysis at Brown’s NASA-funded Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB), led by Brown planetary scientist Ralph Milliken. It’s the latest in Brown’s long history of working with sensitive extraterrestrial samples. Scientists hope the samples will unlock clues about the origins of life on Earth.

Helming the Lunar Recon Team/2023

Brown lands a $7.5 million NASA grant to lead a national team of 50 scientists known as LunaSCOPE—Lunar Structure, Composition, and Processes for Exploration. The researchers—24 of them from Brown—will examine the Moon’s origin, evolution, and structure to facilitate NASA’s future exploration of the moon.—Victoria Liu ’28