It's Not Time Yet

One of the most talked-about videos on the Web this fall had nothing to do with the presidential debates or Ellen DeGeneres’s dog troubles or snakes swallowing baby hippos. It was a September 12 lecture at Carnegie Mellon University delivered by a computer science professor named Randy Pausch. His words fell into the academic tradition of hypothetical last lectures, as in, “What would you say if this were your last lecture?” Only this one wasn’t hypothetical.

Pausch ’82 has pancreatic cancer, and his doctors estimated that he had three to six months of healthy living left. “That was a month ago,” he told the audience. “You do the math.”

Four hundred people packed the auditorium that night. In the front row sat Pausch’s wife, Jai. The crowd included current and former students, colleagues, and friends who, after hearing this would be Pausch’s last talk, had flown to Pittsburgh from all over the world. They rose to their feet when Pausch stepped on stage. Hushing the applause, he mock-chided his friends: “Make me earn it.”

His latest CT scans flashed on a big screen behind him, and Pausch pointed out the tumors where his cancer had spread to his liver and spleen. Still, he said, aside from dying he’s in fantastic health; he dropped to the stage to prove it with a set of one-armed push-ups. He set three topics off-limits for the evening: cancer treatments, his family, and religion. He did confess to a deathbed conversion, however: “I bought a Macintosh,” he said, to much laughter.

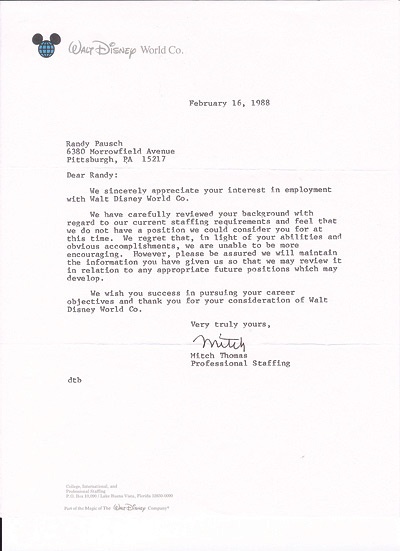

The title of Pausch’s lecture was “Achieving Your Childhood Dreams.” He described his youthful desires to win big stuffed animals at carnivals, to float in zero gravity, to publish an article in the World Book (“I guess you can tell the nerds early,” he joked), to be Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, to design rides for Disney, and to play in the National Football League.

He’d achieved most of those dreams. He experienced momentary weightlessness on a plane NASA flies to simulate what an astronaut experiences in space (the plane is nicknamed “the vomit comet,” and Pausch joked that he felt no need to try it again). His expertise in the field of virtual reality landed him a job creating Aladdin’s magic carpet ride at Disney World and an invitation to write the virtual reality entry for the World Book. Although Pausch never got to be James T. Kirk, he did meet William Shatner, who played Kirk in the series, when the actor came to see Pausch’s lab. And as for the stuffed animals, after Pausch learned to sew he inundated friends and family with his huge creations; he said he was especially productive while avoiding writing his dissertation.

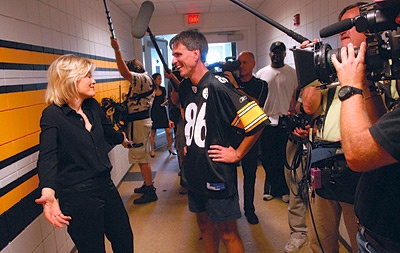

Only the NFL had eluded him—until, that is, word got out about his speech and the Pittsburgh Steelers invited him to practice with them. “I’ll make you guys a promise,” Pausch told them. “You get into that Super Bowl, I’ll live to see it.”

Not in the audience that night were Pausch’s children—Dylan, who is five; Logan, who is two; and one-year-old Chloe. Although they were in bed asleep, Pausch made it clear that his lecture was really intended for them. This, he hoped, would be the video his kids remembered him by.

When word got out about Pausch’s lecture and a video of it surfaced on YouTube, millions of viewers sought out this dying man’s advice about living. His ebullience and courage seemed to captivate both individual listeners and the media. The Wall Street Journal ran two articles about the lecture. Good Morning America broadcast snippets of it.

ABC News named Pausch its “Person of the Week.” “It’s the best two hours you’ll ever spend,” more than a few bloggers noted. (Actually the lecture is only an hour, but it’s preceded and followed by forty-five minutes of tributes.) Newspapers in Israel and South Africa ran articles praising Pausch. He delivered a condensed version of his lecture on Oprah in late October. “I had no idea how much influence her show has,” Pausch says. “Until I walked into a Starbucks afterwards.”

Faced with so many media demands, he and Jai decided that after giving a few high-profile interviews he would stop. His priority in his remaining weeks—or months if they were lucky—was family. (“A friend asked me if I saw the irony of spending time on Oprah,” he says. “But the kids were asleep during the taping.”)

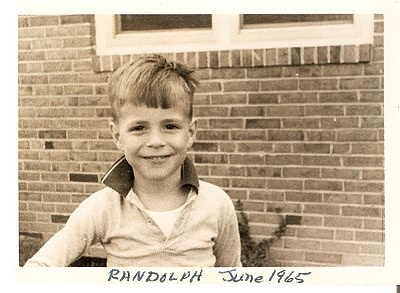

In his lecture, Pausch off ered commonsense advice, life lessons as valuable to grown-ups as they will be to Dylan, Logan, and Chloe. He urged parents to let their kids paint their own rooms and showed photographs of the submarine, the elevator, and, of course, the quadratic equation he painted on the walls of his own bedroom as a boy. “Forget the resale value,” he told parents.

Achieving childhood dreams, said Pausch, is not always easy. Brick walls are not there to stop us, he said; they’re there to make us prove how hard we want something. He learned this one early. After he’d applied to Brown and had been put on the waiting list, he called the admission office and pleaded his case, insisting he didn’t want to go anywhere else. An acceptance letter arrived three days later.

During his first year in Brown’s computer science department, he heard stories about a legendary professor named Andries van Dam, who was on leave. “He was like a mythical creature,” Pausch told the audience, in which van Dam sat grinning. “Like a centaur, but a really pissed-off centaur.” The next year, van Dam hired Pausch as a teaching assistant for his introductory computer science class. From the start, Pausch’s brash manner annoyed his fellow TAs. After office hours one night, van Dam Dutch-uncled him. “He’s Dutch, right?” Pausch said, “He put his arm around my shoulders, and we went for a little walk, and he said, ‘Randy, it’s such a shame that people perceive you as so arrogant. Because it’s going to limit what you’re going to be able to accomplish in life.’ What a great way to tell you you’re a jerk,” Pausch marveled.

At Brown, Pausch was one of the night owls who haunted the computer lab, vying for time on Brown’s huge IBM mainframe computer. He wanted to work in virtual reality, and van Dam urged him to apply to graduate school. “It wasn’t the kind of thing people from my family did,” Pausch told his audience.

“We got, say, what do you call them? Jobs.”

Later, in his office at Brown, van Dam explained that from the start Pausch stood out as an extrovert in a field of introverts, the kind of computer scientist who could move the field forward while inspiring and training the next generation. Van Dam wanted Pausch to go to Carnegie Mellon, but the school turned him down. He visited the graduate programs that had admitted him and came back discouraged; Carnegie Mellon was the one place he wanted to study. So van Dam called the department chair. When he got off the phone, he told Pausch, “Be there for an interview at 8 a.m. tomorrow.” Pausch talked his way in—another brick wall down.

Norm Meyrowitz ’81 was Pausch’s TA during his freshman year at Brown and, according to Pausch, a friendly rival. “He’s like a bulldog, but a very friendly bulldog,” Meyrowitz said in a phone interview. “Over the years he has mellowed. We’ve all mellowed. He used to be a barking bulldog; now hemeows a lot.” Meyrowitz went on to lead product development at Macromedia, the software company that has produced such programs as Flash, Shockwave, and Dreamweaver. For the Brown computer science department’s twenty-fi fth anniversary, he headed a $4 million drive to endow a professorship in van Dam’s honor. “I said we should get someone like Randy,” Meyrowitz says. “Someone who can get people not just to think but to do.” Just as van Dam has created two generations of computer scientists, Pausch has done the same, fi rst at the University of Virginia and then at Carnegie Mellon, Meyrowitz said. “He’s the next generation of Andy.”

Pausch was teaching at Virginia when he received tenure. To celebrate he took his entire research team to Disney World. “How can you do that?” a colleague asked. “It must have cost a fortune.” “These people just busted their ass and got me the best job in the world for life,” Pausch replied. “How could I not do that?”

“Show gratitude,” he advised his Carnegie Mellon audience in September.

In 1995, Pausch began a six-month sabbatical at Disney’s Imagineering Virtual Reality Studio, working on the Aladdin project. Then he returned to Carnegie Mellon, where he and his team developed Alice, free 3-D software designed to reverse the shrinking numbers of computer science majors and graduate students by teaching middle school and high school students how to create programs. They recently persuaded the game company Electronic Arts to let them use the Sims 2 characters. Reasoning that younger children, especially girls, would be more attracted to creating programs that told stories, one of his graduate students created a version of Alice based on narratives.

With a colleague in Carnegie Mellon’s drama department, Pausch created a legendarily popular interdisciplinary course, called Building Virtual Worlds, that drew not only techies but students from all over the university. Each term, several hundred students and faculty would line up early to witness the final exhibition.

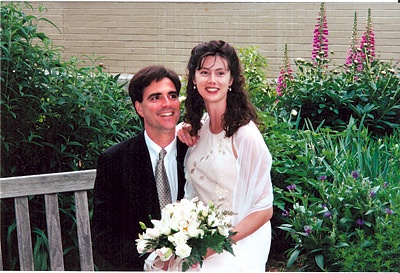

In 1998 Pausch was invited to deliver a speech on building virtual worlds at the University of North Carolina. His escort was a strikingly beautiful grad student named Jai Glasgow. Before meeting Pausch at the airport, she’d done some preliminary scouting on the Internet and had concluded that he was probably gay. He was handsome, he was still single in his late thirties, and he sewed all those stuffed animals (his creations can be seen on his Web site).

Pausch says he was instantly smitten and asked if Glasgow would join him for a glass of wine after his hosts took him to dinner. He surprised them by racing through the meal. Not only that, he moved back his plane reservations a day in case he could persuade Glasgow to join him for dinner the following night as well. Pausch was scheduled to host a guest speaker of his own back at Carnegie Mellon, and he called to say he wouldn’t make it. “I just told him the truth,” Pausch says. Fourteen months later he called the man back to invite him to the wedding. That same year, Pausch was promoted to full professor.

After the September 12 lecture, his Carnegie Mellon colleagues presented tributes, including the announcement that a footbridge connecting the art and computing buildings would be named in Pausch’s honor. Pausch presented a cake to Jai, whose birthday he’d missed the day before while traveling. They embraced on stage, weeping. Finally his old mentor Andy van Dam took the stage. He described the young Randy as cocky and stubborn—observing that these were adjectives frequently used to describe himself. “I prefer to think of them as features, rather than bugs,” van Dam said. Once again the audience cracked up.

Pausch’s only failure as a student had been his refusal to use chopsticks, a critical techie skill since Chinese restaurants are a favorite locale for brainstorming. He even threatened to withhold Pausch’s diploma unless he mastered chopsticks. As van Dam told this story, the screen behind him projected a photograph of the young graduate opening his Brown diploma to find only a Chinese menu inside.

Pausch discovered he had pancreatic cancer during the summer of 2006. He’d been troubled by bloating and had developed jaundice. Scans revealed a tumor. Only 4 percent of patients with such tumors survive as long as five years. His surgeon removed a third of Pausch’s pancreas and stomach, all of his gallbladder, and several feet of his small intestine. After the surgery his former Brown roommate, physician Scott Sherman ’82, fl ew down to sit at his bedside. In addition to emotional support, he provided critical medical advocacy, Pausch says. “You can’t advocate for yourself when you’re that sick.”

Just weeks later, he began a brutally toxic combination of chemotherapy and daily radiation at The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.The kids moved in with Jai’s sister and brother-in-law in Norfolk, Virginia, and Jai came to take care of Randy for the two-month-long treatment. When she went home to be with the kids, Sherman and other friends came to Houston. Pausch was violently sick for the duration; by the end his weight had dropped from 182 pounds to 138. He could barely walk. Then he moved home to Pittsburgh and began four more months of palliative chemotherapy. By summer he’d regained his health, was up to 168 pounds, and was able to exercise again. He still has digestive troubles and abdominal cramping, and he has to eat multiple small meals each day. But, as he puts it, that’s a small price to pay for walking around.

In August the other shoe dropped. His scans showed large tumors on his liver and smaller ones peppering his spleen; the cancer had not only returned, it had metastasized. With the prognosis grimmer than ever, Jai, Randy, and the kids moved from Pittsburgh to Chesapeake, Virginia, to be near her sister and her family.

Yet with all the recent publicity has come surprising good news: Pausch’s October scans showed that the tumors in his spleen had disappeared and those on his liver were either stable or smaller than they’d been a month earlier. Suddenly time seemed less pressing. He sewed Halloween costumes for the entire family. They went trick-or-treating as the Incredibles. His November scans brought even better news: the tumors were continuing to shrink.

In early November he and Jai took a much-needed three-day trip, without kids, to Williamsburg and Charlottesville, where they saw the band the Police perform at the University of Virginia. Friends arranged for them to go backstage and meet the band. Jai, a huge Police fan, got her picture taken with Sting. In the background her husband can be seen grinning.

“Before this whole thing went viral,” Pausch says, he figured his claim to fame would be a video he made on time management. It’s a topic he’s become quite expert at. “I’m not attending faculty meetings, that’s for sure,” he says. He quit teaching when he began cancer treatments and is now mostly consulting for his lab. He jokes that he has a full-time job doing public relations for the university.

Ever the multitasker, he squeezed in several phone interviews with the BAM while his children were napping and he was riding his bike around Virginia. As he rode, his breathing became strained at times. “My stamina is for crap,” he said. “The chemo has wiped out my hemoglobin cells, so it’s like exercising at altitude.” Still, he said, “I can play basketball again.” And he can play with his children. “Having three small kids is a two-edged sword. They’re hard on your stamina, but they’re also little joy inducers.”

Pausch says he received about 5,000 e-mails in the month after his lecture. “Some are trying to save my soul,” he said, “or to tell me how to cure my cancer. I get tired of people typing in all caps and telling me I’m GOING TO HELL.” He and Jai switched to an unpublished phone number, fearing some zealot would decide to speed their kids on to the next world. Most of the e-mails have expressed support, though. “And there have been some gems,” he says. “The people who write to say, ‘I lost my dad when I was five, and here’s what he did that helped me.’ Those are actionable.”

Action seems to be Pausch’s natural state, and even with the direst prognosis possible, he’s still making plans. He bought tickets to go scuba diving off Little Cayman in the Caribbean with Scott Sherman and two other friends in early December. His doctors have told him he’ll probably be around for Christmas. “I might even make it to Valentine’s Day,” he says.

Beyond that? “Jai loves to have fresh flowers in the house,” he says. He’s arranged for weekly deliveries for a year after his death. The fifty-second week, the bouquet will come with a note: “Now it’s time to get a new guy.”

Charlotte Bruce Harvey is the BAM’s managing editor.

Enabling the Dreams of Others (An Excerpt from Randy Pausch's "Last Lecture")

“So, you know, in case there’s anybody who wandered in and doesn’t know the back story, my dad always taught me that when there’s an elephant in the room, introduce them. If you look at my CAT scans, there are approximately ten tumors in my liver, and the doctors told me three to six months of good health left. That was a month ago, so you can do the math..… So that is what it is. We can’t change it, and we just have to decide how we’re going to respond to that.… If I don’t seem as depressed or morose as I should be, sorry to disappoint you. And I assure you I am not in denial. It’s not like I’m not aware of what’s going on. My family, my three kids, my wife, we just decamped. We bought a lovely house in Virginia, and we’re doing that because that’s a better place for the family to be, down the road..…

“All right, so what is today’s talk about then? It’s about my childhood dreams and how I have achieved them. I’ve been very fortunate that way. How I believe I’ve been able to enable the dreams of others, and to some degree, lessons learned. I’m a professor, there should be some lessons learned, and how you can use the stuff you hear today to achieve your dreams or enable the dreams of others. And as you get older, you may fi nd that ‘enabling the dreams of others’ thing is even more fun.”

Click here to download either a complete transcript or a video of the talk. The site also has a link for watching the video online.