Each month for a year, Max Deutsch ’11 vowed to master something playful yet “ridiculously hard” during his spare time.

Max Deutsch ’11 believed he could land a backflip. But his feet didn’t. They remained firmly rooted to the ground, even though he willed himself to launch upwards and back.

Standing on the springy blue floor of San Francisco’s AcroSports gym as preschoolers practiced somersaults, Deutsch stared hard at the wall. Over the past two weeks he’d completed 45 backflips from within the safety of a special harness, to help make sure, as he put it, “I’m not going to die.” He knew he had the physical ability to do the backflip without the harness, but it wasn’t until he stepped out of it that he realized how psychologically comforting it had been.

“The adrenaline started pumping just thinking about throwing myself upside down,” he says.

He’d put in too much work to back out now, though. His neck was stiff, his shoulders were tired, his knees had trampoline burns, and he could barely laugh or sneeze because his abs felt torn apart. He’d practiced jumping back into a foam pit, watched countless instructional videos on YouTube, and replaced his favorite snack, sugary Oatmeal Squares cereal, with carrots to help improve his fitness. He’d even practiced giving strangers compliments on his walks home to help his brain learn to overcome fear.

His brain was unmoved.

“Max, please stop doing this,” Deutsch recalls an insistent voice in the back of his head telling him. “This is a horrible idea. I don’t support this.”

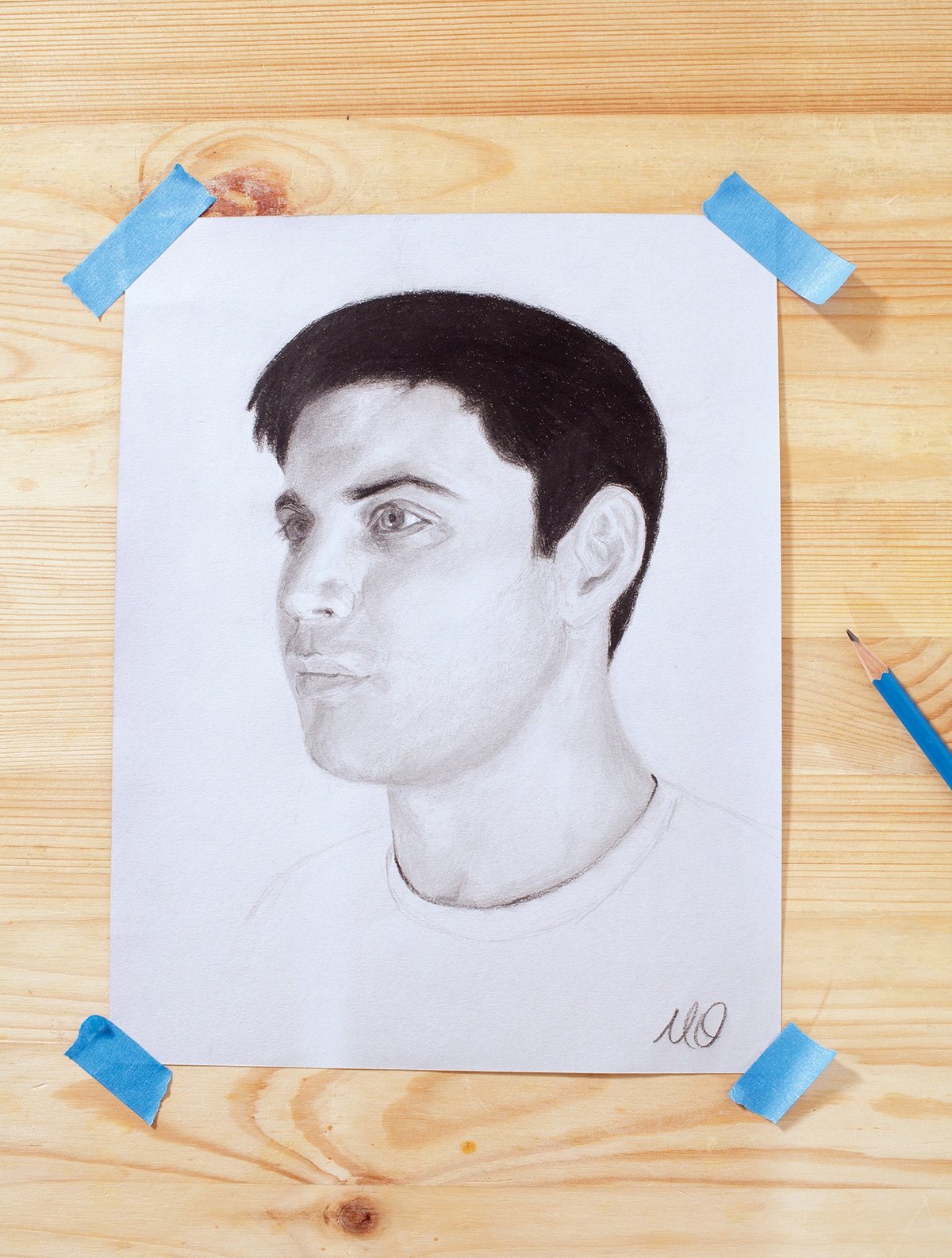

Yet Deutsch had no choice. For his daily blog, Month to Master, he’d told his followers—who would eventually number 100,000—that in the month of February he would successfully land a standing backflip. Each month he picked a “ridiculously hard” challenge that required developing mastery of a difficult skill in a short amount of time. Over the previous few months since he’d started the challenge in November 2016, he’d lived up to the task. He’d learned to memorize the order of a deck of cards in fewer than two minutes. He managed to draw a realistic self-portrait. And he’d solved a Rubik’s Cube in under 20 seconds.

The backflip, with the element of fear and the possibility of bodily harm, was the toughest challenge yet. Deutsch lowered himself, knees bent at a 45-degree angle. He dug his toes in and felt his mind constrict its entire focus onto what he was about to do. He then threw everything he had into propelling himself upwards, thrust his arms back to generate power, and tucked his knees in at the peak of his jump, almost enough to spin around and land on his feet.

Instead, he landed on his head.

Shaken but okay, Deutsch went back to the harness. “Mom, don’t watch this,” he titled the day’s blog post and video of the inadvertent head-plant. Deutsch became obsessed with getting it right, constantly picturing himself landing the backflip in his mind. After a couple more weeks of sore abs and successful (harnessed) landings, the spooked voice in the back of his head began to recede.

Finally, when the nagging voice was all but quiet, Deutsch decided to go for another attempt, unassisted. This time, he nailed the flip.

“I couldn’t stop smiling. The chemicals in my brain were going crazy,” Deutsch remembers. “Overcoming this fear was like unlocking a secret room in my brain that I didn’t know I had.”

Make Time for Play

Deutsch is not a Netflix binge-watcher. If he wakes up on a Saturday morning with an idea for a painting, he’ll go straight to the store to buy a canvas and make a day of it. He once heard about a photograph of a potato by a famous artist that sold for more than a million dollars. Deutsch rushed home, grabbed a potato, set up a lighting kit and tried to replicate the picture. (It didn’t sell.)

Growing up, Deutsch made Andy Warhol–inspired portraits of friends and family out of Legos. He tried to create his own essay-writing software. He also developed visual effects in high school that ended up as part of a screening at the Cannes Film Festival. At Brown, where he concentrated in math and economics, Deutsch founded the Intercollegiate Finance Journal and worked on a series of start-ups.

He also embarked on a Protestant-esque drive toward relentless self-improvement. These days, sugar and alcohol have long been eliminated from his diet. He listens to dozens of nonfiction audio books a year at speeds three to four times normal (he designed his own app to do so). With intense eyes, his own businesses (Openmind, which offers a learning app), and a body that shows he works out regularly, Deutsch may be Type A, but he’s a Type A who likes to make time for play—to do random, spontaneous things for pure enjoyment. (On April Fools’ day, he set up a realistic fake news story about himself being arrested for corporate misconduct through a sponsored Facebook ad attributed to the Wall Street Journal that showed up on the news feeds of family and friends.)

Once he graduated and moved to Silicon Valley, where he has pursued a full-time career as an entrepreneur and start-up consultant, Max started to feel locked in. Then it hit him: he wasn’t giving himself time to play.

He conceived Month to Master as a way to force himself to make space for the things he loved. “I thought, ‘Can I take this thing I’ve always loved doing—learning—and put structure around it and pursue it to the fullest extent?’” Deutsch asks.

He wrote down all the things he might want to pursue and eventually narrowed the list to twelve physical, mental, and artistic challenges. To track his progress and hold himself publicly accountable, he posted a near daily update through Medium.

Ditch the Fear

On a sunny day in San Francisco in late September, Deutsch stepped up to the mic and prepared to do something he had never, ever imagined he would do before: freestyle rapping in public. He stood before a knot of staring, expectant tourists in the center of Union Square and slapped out a beat on his electric guitar—and began to kick it.

His initial attempt at freestyle rapping—at the beginning of that month—had proved pitiful. In a video documenting that first attempt, Deutsch stares blankly at the camera and mumbles out less than a minute’s worth of what might generously be called rhymes, offbeat to a background musical track:

It’s sunny outside, not going to rain. I’m spitting with very little game. This is putting me in pain. Honestly this embarrassing .… What rhymes with embarrassing?

If anyone understands learning curves, though, it’s Deutsch. He realized that to be able to rap on the spot, he’d need to build up his rhyming vocabulary to develop what rappers call a flow.

He set a metronome to a manageable 60 beats per minute, found a random word generator website, and started trying fifteen minutes a day.

Captain, Provoke, Empire popped up on his screen. Tentatively, but then with more confidence, Deutsch gave it a go:

I’m gonna be spitting, with my computer on the table

Got more channels than basic cable

Here I am, just sitting here rappin’

Steering this freestyle ship like I’m the cap’n

I’m gonna get my rappin’ license revoked

Cause my rhymes get all the other rappers provoked

And now I’m gonna take it even higher, spittin’ fire

Building up my rappin’ empire

He began to rhyme compulsively. Strolling down the aisles at Whole Foods, a cut of wild Atlantic salmon became “styled, frantic jammin’.” The package of unsweetened applesauce turned into “one weakened rapper boss.” And the box of Kashi Organic Cinnamon Harvest? “Watch me pour magic, sinner gone artist.”

A few weeks in, the word-generator website shut down, so Deutsch built his own. He started rapping for his friends at parties. They couldn’t believe the transformation, but Deutsch knew that to prove himself he had to commit fully and rap in front of strangers. Just as with the backflip, something deeply rooted and irrational held him back. At Union Square, in the moments before he began, an immense anxiety gripped him, Deutsch says—until he opened his mouth and dropped a line: Kickin’ it on the microphone, we gonna examine the rhymes under the microscope.

“After the first line or two you realize you’re not going to die,” Deutsch says. “My survival is not at risk expressing myself that way in front of a group of people. By the end I had zero fear.”

He incorporated the crowd: I’m on the mic makin’ a racket, dude’s walking past in a green jacket.

People he rhymed about smiled. His friends clapped along. Someone offered twenty bucks. He stayed out for nearly four hours, having fun.

When the time came at the end of the month to record a three-minute continuous freestyle rap, Deutsch had no trouble.

Enjoy the Process

Deutsch believes all of us are capable of learning new skills at any point. “I think that we are all born with this desire to learn or explore,” he says “and over time we become more protective of our identity and fear failure.”

There is a notable purity in Deutsch’s project. Following his successful creation of self-driving car software—May’s challenge—Deutsch was flooded with inquiries about how he planned to monetize his work. He dismissed the idea. He was happy with his income from his existing business. “Compared with commercially oriented skills, I tend to much prefer timeless skills—skills that can be enjoyed and constantly worked on forever,” Deutsch wrote in a blog post about his solving the Rubik’s Cube.

Rather than attaining enjoyment only from finishing a challenge, Deutsch found fulfillment in the process of learning itself. Part of the fun was simply figuring out what he had to do to actually learn the skill and to push his limits. He is a firm believer in the principle, outlined by Malcolm Gladwell’s ten-thousand hour rule, that through systematic and deliberate practice nearly anyone can master any skill.

Anders Ericsson, the researcher who inspired Gladwell’s famous rule, would agree. Except, Ericsson says, when it comes to a few things, such as solving crossword puzzles, which require seemingly random and scattered knowledge that cannot be cohesively and deliberately learned.

“Naturally, that was what I decided to try and do,” says Deutsch, who spent the month of July attempting to prove Ericsson wrong and develop a way to become quickly adept at solving, in one sitting, a New York Times puzzle. He quickly realized that brute force—just trying to solve a whole bunch of crossword puzzles to prepare himself—wasn’t going to do the trick. He decided he’d have to learn to identify patterns and try and find a way to familiarize himself with the most frequently used clues and answers.

Deutsch discovered that a crossword puzzle aficionado had been updating a website for years with the words and clues for every day’s Times puzzles. The computer-savvy Deutsch “scraped” the site, compiling a comprehensive spreadsheet (“Ali,” as it turns out, is the most common answer in a Times crossword). Since there were more than 100,000 clues and the clock was ticking, he narrowed the list down to just the Saturday ones (still nearly 13,000).

He then built an app—his own crossword trainer—that gave him lists of 100 clues at a time. On his hourlong morning train commute to work, Deutsch used a language learning technique called “space repetition” that allowed him to retain thousands of words after only a few training sessions. (He’d focus first on one set of a hundred for six minutes, then on another set, then combine them, and so on.) Combining his mass memorization attempt with frequent practice took 46 hours, but sure enough, by the end of the month, Deutsch could solve a Saturday puzzle in just more than 20ß minutes.

To learn to rapidly memorize cards, Deutsch relied on the brain’s superior capacity for visual memory and mentally paired each card in the deck with a famous person (the four of diamonds became Danny DeVito; the queen of spades, Cleopatra). He mapped out a detailed route, in his mind, of his childhood home and assigned 52 different locations: dresser, closet, bed, toilet, etc., and as he flipped the cards he visualized each celebrity in the given location. To hyperfocus his concentration he took to wearing “memorization glasses” (two cards taped to a pair of glasses like horse blinders) on his train commute. The whole process took him a little more than 22 hours to perfect, about the same amount of time necessary to binge watch two seasons of Game of Thrones.

In December, an intensive online drawing class and ample YouTube videos allowed him to sketch his own portrait. In August, an ungodly amount of protein and a hellish workout schedule saw him complete 40 pull-ups in a row. In June, hours and hours of training his mind to recognize musical notes allowed him to claim perfect pitch by identifying 20 random notes.

Other challenges included learning enough Hebrew words and grammar to speak for 30 minutes with a fluent friend on the future of tech, and upping his guitar game enough to perform a five-minute improvisational blues solo. Each completed challenge was satisfying, but what Deutsch really cared about was being immersed in the learning experience. “The worst day of the month was the day after I had completed the challenge,” Deutsch says, “because there was nothing left to pursue.”

Fail with Flair

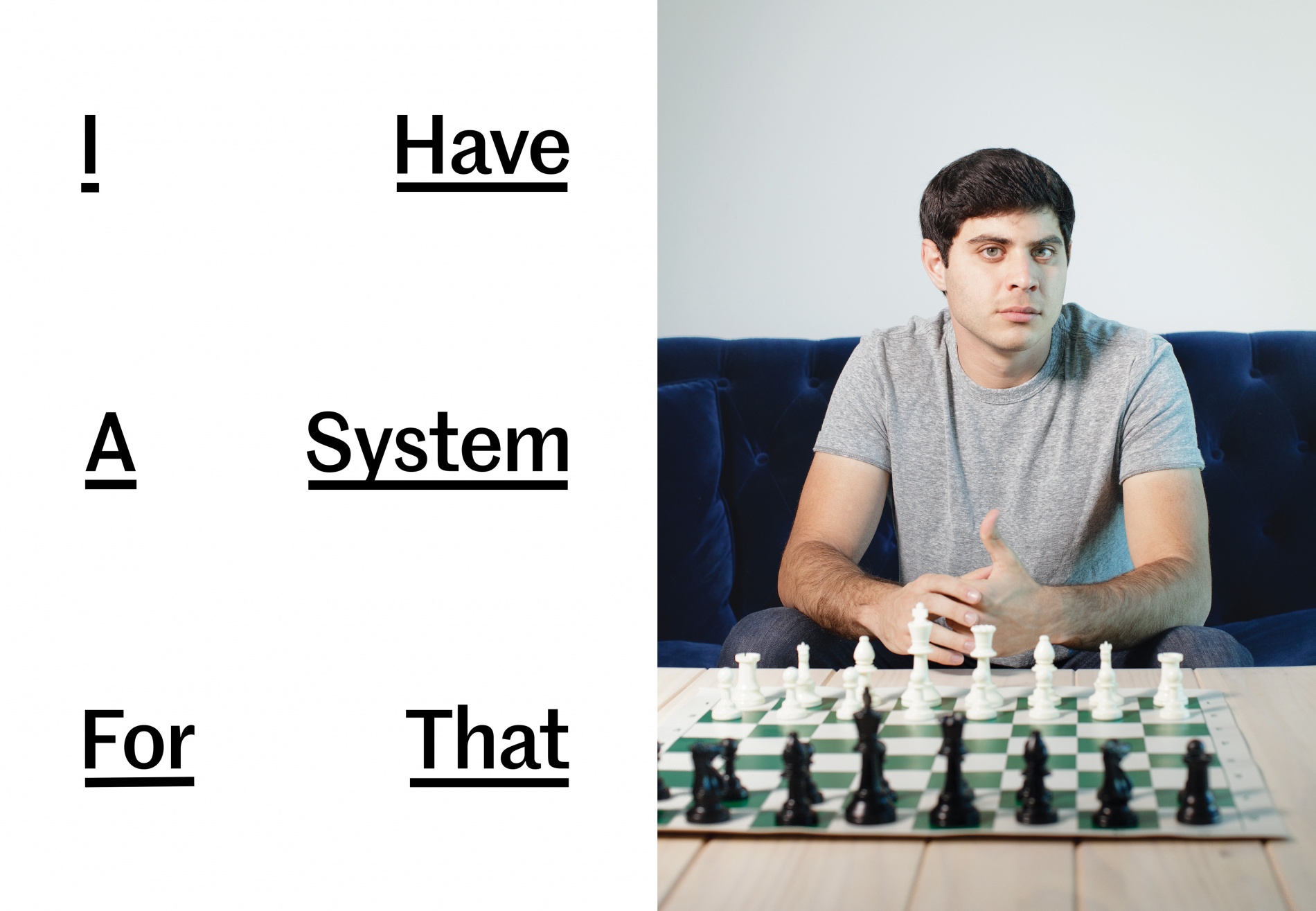

With eleven successful months behind him, Deutsch faced his toughest challenge: beating the current World Chess Champion, Magnus Carlsen.

Deutsch had originally intended to play against a digital Carlsen on the app Play Magnus. But the Wall Street Journal, sensing a story, had other ideas and offered to set up a match in Hamburg, Germany. “I’ve agreed to this challenge,” Carlsen told the Journal, “because I’m genuinely curious as to what he can do in a month.”

Deutsch figured he couldn’t beat Carlsen by playing a normal game of chess. So, relying on his degree in pure math and his computer science background, Deutsch attempted to construct an algorithm that would allow him to figure out each optimal move, essentially computerizing his mind. Of course, Deutsch admits in retrospect, it would have taken him way too long to identify the correct move for each and every turn, using this strategy. But Deutsch was never one for tempering his expectations. In the end, he didn’t get a chance to see how his brain would function because he underestimated the amount of time it would take his computer to generate the algorithm. By the time he arrived in Hamburg his computer was still processing it. He would have to play Carlsen normally. Carlsen, however, didn’t know this.

After a 13-hour flight, Deutsch waited in a fancy hotel lobby for Carlsen to arrive as cameras rolled. When the grandmaster entered the room with his slicked-back hair and suit, Deutsch smiled. “It’s not often,” he says, “that you get a chance to play the number one in the world in anything.” Deutsch was nervous, but knew he had nothing to lose. He started with a pawn to E4; he’d heard it was a good move. Carlsen responded, quick and intimidating. “For the first few moves he had to take the game really seriously,” Deutsch says. “He was giving as much thought as I was and that was a really cool feeling.”

After about a dozen moves, Carlsen twitched. When he saw Deutsch making blunders, he eased up. The game ended after about twenty minutes. They then recreated the game, Carlsen offering Deutsch some tips for improvement. It had been a curious meeting, Deutsch acknowledged—a 20-something chess prodigy who had spent his whole life dedicated to the absolute mastery of one domain facing a jack-of-all-trades who dabbled at a high level in intellectual and artistic odds and ends. “I was really taken by Carlsen,” Deutsch says, “from the standpoint that he had to sustain his love and commitment for a really long time to get to the level he was at. I found that really beautiful.”

Carlsen agreed to a rematch once Deutsch figures out how to make his algorithm work. In the meantime, Deutsch has been forced to learn the game the slow, old-fashioned way.

This year, Deutsch has put Month of Mastery on hold (for a new version, he’s interested in learning to dunk a basketball). Instead, he’s working on a yearlong book project, Yearbound, published in daily posts on Medium.com, so he can respond to and incorporate reader feedback.

While he insists Month of Mastery was first and foremost a personal project, he hopes that if there’s one bit of advice people can take away from his project and apply to their own lives, it’s that we can always make time for the things we love and are interested in.

“It’s really easy to be busy and let obligations prevent us from living the lives we want to live,” Deutsch says. “But I’m not convinced we need to let that be true for us.”

Jack Brook ’19 is still too scared to land a backflip. His writing has appeared in the Santiago Times and the Jerusalem Post.