Nevertheless, They Persisted

Meet seven extraordinary students graduating into a new world.

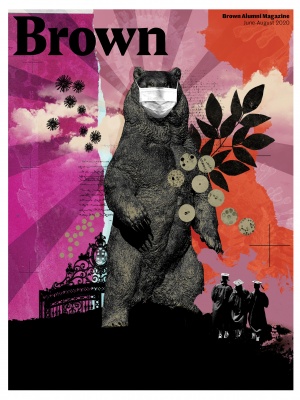

“Defending my dissertation over Zoom was weird,” admits anthropology PhD recipient Omar Alcover. “On the other hand, my family was able to attend.” This year’s graduates had their last semester cut short by COVID-19. Some dove into the relief effort, some just had more study time, others faced serious family financial and health issues. They couldn’t walk out through the Van Wickle Gates and they’re joining an economy in recession, but most remain optimistic. For Alcover, even not having a traditional Commencement had a silver lining: “Having the virtual option makes it more accessible.” Ever forward. Ever True.

Jeannette Gonzales Wright

Deaf Advocate

It wasn’t easy for Jeannette Gonzales Wright ’16 (PLME), ’20 MD, to grow up in L.A., the child of two parents who are Deaf, one of whom—her mother, Tess—was also a Filipina immigrant. Not only did the family experience financial hardship, with her father sometimes having to ask for money in public when food stamps ran out, but she would often be mocked by other kids while communicating with her parents in American Sign Language (ASL). “People would make obscene gestures when they saw us communicating,” she says.

The flip side was that her parents brought her up in a vibrant community of Deaf people, with some of her closest friends being other CODAs (children of Deaf adults). When she got to Brown, where she met no Deaf students, she deeply missed that world—until she enrolled in an ASL class. “People who speak English still study it to learn more about it,” she says. “The class gave me a more refined sense of ASL grammar and an updated vocabulary.” The professor, Arkady Belozovsky, who is Deaf, not only introduced her to the rich culture and history of the Deaf community, but instilled in her a sense of pride in her parents and the community she was raised in. “He helped me recognize so many beautiful moments that I’d witnessed.”

The class also attuned her to the fact that many children born deaf are still not identified as such until they are toddlers, which can affect their early education, often setting them back for life. That, she says, was the case with both her parents. She’s currently finishing a thesis, for a masters degree in population medicine she’s been pursuing alongside her MD, on “how parents with deaf or hard-of-hearing kids make decisions for them, such as do they teach them ASL, spoken language, or both. That’s a huge debate.”

Gonzales Wright has already begun her advocacy in the Deaf community, currently chairing the health committee for Rhode Island’s Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, creating a survey to find out how many Deaf folks in the state don’t have key supports, such as their own primary-care physician.

As for her own medical career, “I want to be a clinician-plus,” she says, “someone with a Deaf patient load but who also advocates politically for the Deaf community.” For too long, she says, Deaf people have lagged behind in education, employment, and income—not because of inherent intelligence but because of societal marginalization. “Even a shortage of interpreters in healthcare settings, schools, and other places contributes to this,” she says.

Meanwhile, something else pretty great came out of that Brown ASL class—her fiancé, Alex Laferrière ’20 MPA, a media production specialist at Brown’s Watson Institute who also grew up the child of parents who are Deaf. “My relationship with him took my understanding of my identity and experiences to a whole new level,” she says. “We went out one day for a short walk around campus and ended up talking for hours about our upbringings. I realized I was not alone.”—Tim Murphy ’91

Griffin Kao

Connecting People

By the end of four years at Brown, it’s almost easier to ask what Griffin Kao ’20 hasn’t done. He’s published a book, won the national ultimate frisbee championship, developed numerous apps, helped teach a class, and manufactured his own cheaper version of a FitBit to make health technology accessible to more people. Classmates describe him as one of the friendliest and most thoughtful people they know.

Entering college, Kao quit swimming and devoted himself to the Brownian Motion Ultimate team. A D-Line Cutter (similar to the defensive safety position in football), he remembers having to practice in five layers in the middle of winter when catching the disc stung; the layers stayed on as the weather warmed to prepare for temperatures at the finals in Austin. The training paid off: Brownian Motion crushed widely favored UNC in an upset to become 2019 National Champions.

Off the field, Kao co-authored Turning Silicon Into Gold, a book published by Apress, an IT book publisher, that analyzed a range of case studies on interesting phenomena at the intersection of tech and business (like why the second competitor in a market tends to beat out the first). It wasn’t his first publication—he produced a novel in high school and has been writing since his elementary grades.

Yet what Kao’s really been focused on is using technology to help bring people together and build communities. He’d never studied computer science before Brown but became fascinated with using coding to create platforms and apps that could enhance relationships and encourage personal and professional growth.

“How do we make something that doesn’t replace human interaction but augments it?” Kao asks. He seeks to help make people “more conscious of how they react and how they respond emotionally to the people they know.”

Through his company, Revive Brand Management, Kao’s been applying what he learned in the classroom to the real world. The ideas were simple at first. “Moodie” is a mindfulness app that allows users to track their moods based on different activities (perhaps hanging out with a certain friend). “Options Ranker” helps groups rank options based on their members’ preferences.

As he gained technical expertise and insight, including an internship with Google, Kao took on more ambitious projects. Right now, he’s developing Artistprof, which he calls “a LinkedIn for creatives”—a networking platform for people in the arts to showcase their work and talent, while making it easier to be discovered and connect with agents and employers.

He’s also working on an app called “Anchor,” designed to help people remain attentive to friendships (remembering birthdays, shared interests, and activities). Kao calls it “anti-social media” because he hopes it will get people offline to interact more in person.

There’ll be plenty of time for Kao to continue to hone his craft working as an assistant product manager at Google after graduating. “I think that role is a good fit for me because it’s less about coding,” Kao says, “and more about thinking how products are built and how to make them valuable to actual people.” —Jack Brook ’19

Ella Satish

Saying Yes

It’s late March, and Ella Satish ’20 (PLME), ’24 MD, who is among the Brown undergrads granted permission to remain in their dorms during the coronavirus crisis, is frustrated that she can’t go help out at Clinica Esperanza. She usually puts in paid time at the nearby community health center as part of her involvement in the Swearer Center’s Engaged Scholars Program, which requires that students do real-life work that links to their classes. Satish, a first-generation-to-college student, is a Latin American and Caribbean Studies concentrator, fluent in Spanish.

“They’re short on people and they need in-person Spanish translators,” she says. “But I have asthma and I’d have to take the bus, so it’s risky for me to go.”

The service-minded impulse is typical of Satish, whose twin passions are healthcare and teaching. Growing up in one of the few Black families in southern New Hampshire, she would often accompany her mother, a nurse, to her night shift at the hospital. “I’d sit around and drink apple juice and look at the monitors,” she says, “which got me into healthcare.” In both high school and college, she worked in an Alzheimer’s/dementia facility, feeding and transporting patients, eventually becoming a certified nursing assistant there.

The interest carried over to studying abroad in Cuba, where she researched the poor Communist country’s maternal mortality rates—which, by some calculations, are lower than those in the U.S., especially for Black women. “There are aspects to the Cuban approach that could improve healthcare even in a capitalist healthcare system like ours,” she says, “such as better holistic supports for the mother, continuity of care across providers, and a focus on primary care and preventive medicine.”

A liberal medical education student, Satish plans to become a doctor—“either an ob-gyn or family medicine with a focus on women’s health,” she says. But as someone who also loves kids (“they’re super-thoughtful”) and currently teaches part-time in three Providence schools (one private and two public), she wants to tie her doctoring into teaching. “I’d like to do patient education in one-on-one or group settings, learning and getting feedback from my patients,” she says. She’s already had a crack at this via Clinica Esperanza’s program teaching patients how to manage things like blood pressure by eating and living healthily.

The coronavirus shutdown notwithstanding, Satish’s schedule is always packed. “I use Google Calendar a lot,” she says. But she doesn’t feel overtaxed. “My sophomore year, I started saying yes to things that don’t feel like work to me,” she says. They include the women’s club basketball team, being a freshman peer advisor with the Meiklejohn Program, and programming events at the Brown Center for Students of Color.

“I offer myself as a resource whenever I can, because I’m in a place of privilege at Brown,” she says. “That brings me joy.”—Tim Murphy ’91

Joseph Novak

Modeling Climate Change

Joseph Novak ’20 arrived at Brown skeptical about climate change. Now, he is helping shape the way scientists study it.

Raised in conservative Raleigh, North Carolina, Novak had been taught to be skeptical of climate change. But after taking a biology course and becoming both frightened and convinced, Novak decided to focus his studies on climate science. He joined the lab of geo-chemistry professor Yongsong Huang, taking on an undergraduate research project that Huang warned him would likely never work.

The goal of Novak’s research was to find a better way to reconstruct past sea surface temperatures, which would help scientists create more accurate models of climate change.

Scientists rely on alkenones, or chemical fats made by algae, to determine past ocean temperatures. When algae die, their alkenone sinks to the bottom of the ocean floor and can survive in the sediment there for millions of years, Novak explains. Algae produce different kinds of alkenones depending on the temperature, and the current method for analyzing alkenones cannot detect them above 28 degrees Celsius. That’s because scientists have mainly studied one type of alkenone that has 37 carbon atoms and used it as an index for past temperature. But there is another form of alkenone with 38 carbon atoms and it has a potentially greater temperature range. Novak was looking for a way to analyze this type of alkenone more efficiently—although it is generally much harder to find and, until only a few years ago, could not be analyzed accurately or at speeds that made it practical to study.

Novak made his breakthrough as a result of a panic in the fall of 2018. He and a grad student working on a separate project were slated to give presentations at an upcoming conference, but data from the algae fat eluded them. Reading through old scientific papers and experimenting with different techniques, they found something that seemed to work—a strong enough filter to remove the rest of the chemicals that are typically found in the sediment, but not so strong as to eliminate the key chemical compounds they wanted to analyze.

“We came up with it really kind of out of desperation,” Novak says. “We both wanted to have data to present at this conference.”

Returning from a spring semester abroad, Novak threw himself into refining the method over the summer, then spent his senior year working on a thesis that would test ocean sediment from all across the world to prove the method was accurate. He could now analyze six samples an hour—making the process more than ten times faster than before.

However, the sediment samples Novak needed are rare and coveted by the scientific community. He sent requests to different oceanographic institutes housing sediment from the coast of Antarctica to the middle of the west Pacific Ocean.

Not all of the institutions were interested in helping an “undergraduate at Brown” complete his senior thesis; the emails went unanswered for months. So Novak changed tactics and called himself a “researcher at Brown.” The replies came a lot quicker.

“I didn’t impersonate a professor, but a lot of times they thought I was a professor and I never corrected them. I wanted to make sure they sent me my stuff,” Novak explains.

So far, he has demonstrated his process can analyze chemical compounds in temperatures up to 29.5 degrees Celsius. Final lab work has been put on hold until the pandemic abates, but Novak says he expects to prove it can work in up to 30 degrees. “The results of his senior thesis research will very likely have far-reaching impact for the study of climate change,” says professor Huang.

“When I started the project I was 19 and had no idea what I was doing, but that didn’t stop the grad students and professors from taking me seriously and trying to help,” Novak reflects. Increasing our understanding of past ocean temperatures by a couple degrees may not seem like much—but given that an increase of two degrees in the coming decades will likely be catastrophic for the planet, he argues it may help us adapt to our changing world.

Novak will head to a PhD program in oceanographic science at UC Santa Cruz, where he’ll continue to use the model he developed. But first, he’s accepted a Fulbright to study in Russia.—Jack Brook ’19

Vanessa Garcia

Finding a Superpower

“I love Brown,” says Vanessa Garcia ’20.5, a Business, Entrepreneurship, and Organizations (BEO) concentrator with an emphasis on justice for people with disabilities, “but if you’d asked me in 2017, I’d have said I wanted to burn it down, I hated it so much.”

That’s because, in Garcia’s telling, they (Garcia identifies as gender nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns) had a rocky relationship with the University until their student activism changed things for the better. Freshman year Garcia, who grew up in San Diego, was a high-speed superstar, nabbing straight As, making friends left and right, and zooming from activity to activity. But when they returned second semester, they...crashed. “I couldn’t leave my bed for days,” they say. “My friends were scared—they didn’t know how to help.”

Garcia, hospitalized, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a mental illness marked by turbocharged highs and paralyzing suicidal lows. In their telling, the University urged them to go on medical leave without really asking what they wanted. “You can’t really object when they’re handing you a consent form to sign,” Garcia says. Back in California, living with their grandparents, Garcia sought treatment, went on meds, learned to cope with their illness via therapy, and applied for readmission—but was refused (with little explanation, according to Garcia) and not readmitted until after they appealed the denial.

“This was a critical point in my activism,” Garcia says. “I wondered how many talented people in the past never got to graduate” under similar circumstances. Back on campus, initially feeling lonely and out of sync with their freshman-year friends, Garcia found others who’d taken mental-health leave, and started working with LETS (Let’s Erase the Stigma), to advocate on behalf of leave-taking students. Since its 2013 founding by another student, Stefanie Lyn Kaufman-Mthimkhulu ’17, “We’ve helped shape the entire campus on mental health,” Garcia says. LETS got the University to appoint a student as leave-taking coordinator, someone who would stay in touch with all students on leave. The group also sent care packages to students on leave so they would not feel forgotten by Brown, as Garcia had. According to Garcia, the group also negotiated with Counseling and Psychological Services for a leave-taking and readmittance process that more fully incorporated students’ needs and desires.

Says Timothy Shiner in Brown’s Student Support Services office, “While I’m unable to comment on any individual student’s circumstance, I can verify that we’ve made a number of changes to our medical leave process in the past four years. I think there was a broad sense from students that the process wasn’t transparent and they raised a number of concerns. I am glad...that students are feeling the process better serves their needs now.”

Since their return, Garcia has been a powerhouse on campus, serving as dance captain for a campus production of In The Heights and currently writing an honors thesis on how well corporations are accommodating “neurodiverse” workers, particularly those on the autism spectrum. “Are corporations allowing them to wear headphones, giving them different hours, starting mentoring programs?” Garcia asks. Right now, amid the COVID crisis, is a relevant time to be working on the thesis, they add. “We’re learning that people can be just as productive from home, whereas previously people with chronic pain or single mothers often weren’t allowed to.”

Garcia, who wants to become a disability lawyer, has also served as president of the campus Filipino Alliance and has been involved with Mezcla Latin Dance and Brown Esports, a campus gaming group. “I’ve realized that once you learn how to manage symptoms of bipolar, you can use them as a superpower,” they say. “I see my doctors, take my meds, and avoid all-nighters. A disability can be a huge gift—if you can survive it.”—Tim Murphy ’91

Omar Alcover

Jungle Archaeologist

Many doctoral dissertations are researched from the comfy confines of a library. Not so for Omar Alcover, ’16 AM, ’20 PhD, whose archaeological study of ancient Mayan civilization required him to travel deep into the forests of northwestern Guatemala.

To even begin his research, Alcover had to fly down to Guatemala City, take a nine-hour bus ride to the edge of the jungle, followed by a three-hour truck journey on uneven roads to the Mexican border, then an hours-long boat ride upstream and, finally, hike up rocky slopes to reach Macabilero, an ancient Mayan site that had long remained an archaeological mystery.

One of the reasons the site is a mystery, Alcover says, is because “people don’t visit it, it’s in the middle of nowhere.” Located within the Sierra del Lacandón National Park, the site has been protected since 1997. But the trek and logistical challenges of the research did not faze Alcover, who had discovered his love of expedition archaeology after spending several months in the Guatemalan jungle doing fieldwork as an undergraduate.

Supported by National Geographic, and working closely with his professors and Guatemalan archaeologists, Alcover organized several expeditions to visit Macabilero, starting in 2016. On top of the research, he had to consider questions like how to feed a camp of 12 people for a month with only those supplies that could be carried in by foot on the first day. Techniques included building a mud oven and stove and keeping veggies covered in lime juice. “Omar’s project represents one of the last few ‘expedition’-style projects in Guatemala,” says anthropology professor and director of undergraduate studies Andrew K. Scherer.

The terrain of craggy hills laced with caves hollowed out from the limestone rock had provided indigenous Mayan communities with a natural defensive landscape, which they adapted by building a massive fortress, constructing walls around every natural entrance point in the surrounding valley. Based on ceramic pieces excavated from the site, Alcover believes the walls were constructed around 175 C.E. and he spent years trying to better understand why and how the defensive space was created.

“In 300 B.C.E. and until 2017 there were still people visiting the site with particular ritual uses of the space,” Alcover says. “These are still meaningful places to people.”

During the decades-long Guatemalan civil war, which began in 1960, many from the surrounding communities took refuge in small towns throughout the jungle to escape persecution from the military. “They are the experts of the region and know that land better than anyone else could,” Alcover says.

In conducting his research, which Scherer describes as “transformative,” Alcover took care to collaborate and follow the lead of the local communities of La Técnica and Santa Rita, working with the towns to build a museum that would showcase the materials he gathered.

To better map the site, Alcover and his team used LiDAR technology—a laser sensor mounted on a plane—to map surfaces, along with reconstructing 3D models of the archaeological sites by compiling thousands of photos via a technique called photogrammetry.

While it is still not clear whom the Maya people were trying to defend themselves from, one of Alcover’s biggest insights is that the walls and massive public plazas his team unearthed were constructed by and for communities.

“It’s important to understand the variety of human activity—all the different ways that people create lives and communities,” says Alcover, now working at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on how to bring Meso-American archaeological materials into classrooms. “It is a privilege to be able to study these things and look into the past.”—Jack Brook ’19

Ethan Fecht

Disinformation Warrior

Ethan Fecht ’20 always had a talent for languages, but he never would have guessed that being good at high school Spanish would allow him to become a counter-terrorism intelligence officer and later an expert in the complex world of cybersecurity.

After high school in Hampton, Virginia, Fecht applied to be a linguist for the U.S. Navy, where he spent the next 18 months mastering Arabic. From 2013 to 2017, he worked for the National Security Agency as a counter-terrorism analyst (“can’t get into details,” he says), along the way picking up Italian, French, and Portuguese.

At Brown, he planned to refine his focus on counter-terrorism, but an intro to international relations class exposed him to cybersecurity. There were a lot of similarities—his old job had required him to intimately understand the infrastructure of the internet and how information travels online.

In the summer of 2018, while on a fellowship at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, he co-authored a 56-page report that analyzed 850,000 tweets in the aftermath of the April 2018 chemical attack by the Syrian government against Douma, a rebel stronghold. Fecht and a fellow researcher revealed a coordinated disinformation campaign of bots and trolls (likely from Russia) that attempted to turn the American public against a U.S. missile strike. Their analysis, later published in the Washington Post, showed a surge of new Twitter accounts created in the week following the attack, nearly half of them devoted to spreading disinformation.

After scraping Twitter data, Fecht and his partner painstakingly reviewed thousands of accounts to determine whether they were fake (usually they could tell because a brand new account would have a few hours of frenzied political commentary and then go dead). The accounts typically tweeted in response to President Trump, allowing them to attain high visibility in the comments.

Fecht wanted to go deeper, so he joined Facebook last summer as a “threat intelligence intern” and he saw what he could do with internal data from the company. “The coolest thing about it is probably that we are working on an issue that no one has ever worked on before,” says Fecht of Facebook’s campaign against disinformation.

In counter-terrorism, Fecht dealt with networks of people, deciphering the relationships between them—who gave the orders, who carried them out, and how the military could disrupt that network. Within Facebook’s “information operations,” he applies the same principles but deals with networks in the form of users, pages, and accounts. His job at Facebook (where he’ll work after graduating) is to find out who is behind these networks—whether lone wolves, nation states, or political parties—how to expose them, and how to stop them in the future.

“A disinformation campaign could be one guy running one hundred pages, whereas in counter-terrorism it is actually one hundred guys,” he says. One way to address this issue, Fecht says, could be greater transparency, such as allowing readers to see where the admins of a page are physically located.

With his level of experience, Fecht was a natural to serve as a head teaching assistant of a class on cybersecurity and international relations. Eventually, he plans to get a master’s degree in international relations focusing on cybersecurity strategy.

“We shouldn’t think of misinformation as the last problem we are going to face,” he warns. “We need people with an understanding of international affairs to craft policy.”—Jack Brook ’19