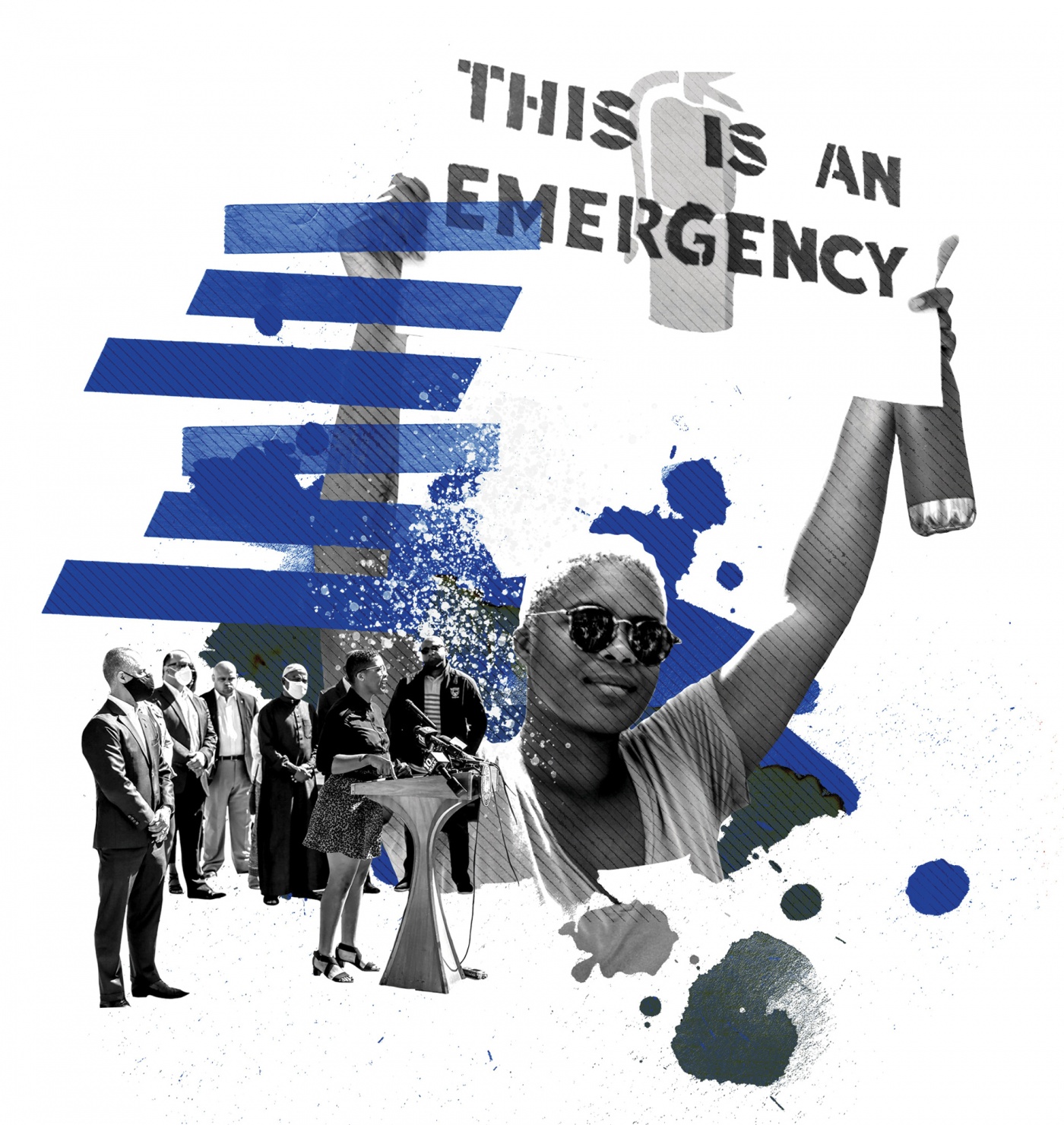

The Reformers

Four young, left-leaning Brown alums, schooled in policy and willing to play the long game—but not too long—are working to make the Ocean State a better place for working-class people like them.

Tiara Mack ’16, Jonathon Acosta ’11, ’16 AM, ’16 AM, Meghan Kallman ’16 PhD, and David Morales ’19 MPA don’t describe themselves this way, but they may be the closest thing Rhode Island has to the “Squad,” the four progressive United States Congress members who were elected in 2018, inspiring strong emotions and overturning conventions. These four Brown alums were recently elected and sworn in to the Rhode Island state legislature, Mack, Acosta, and Kallman as senators and Morales as a representative.

They are all young and passionate about issues that affect working class people. They are grassroots organizers from humble backgrounds, not WASPs with war chests. They say that they intend to reimagine and reshape the state.

Pasts that drive progressive values

Immediately after his swearing-in ceremony, David Morales FaceTimed his mother. He told her “Vale la pena”—it was worth the struggle. That phrase has been the refrain throughout his meteoric educational and political career. And he always wants to prove to his mother—who immigrated to America from Mexico as a young woman, does not speak English proficiently, and has mostly worked minimum wage jobs—that her sacrifices were meaningful.

His mother’s hardships drove him to take community college courses in high school so he could get his bachelor’s degree from UC Irvine when he was 19. Then he earned his master of public affairs degree at Brown when he was 20.

“I think at a very early age, growing up in a single-parent household, you immediately have to take on more responsibility and mature at a faster pace than someone from a traditional nuclear family just due to the fact that you have more responsibilities,” Morales says. “There’s more of an emotional burden knowing how hard your single parent is working and knowing that you do not want to ruin the opportunities they are trying to create for you.”

Tiara Mack’s family also struggled when she was a child. Her mother worked paycheck to paycheck and then was unemployed after she broke her wrist and later her leg. She had surgery but developed an allergic reaction to the metal doctors inserted. Back-to-back operations followed for five years. It was hard to pay for necessities. Lights, water, internet, cable were routinely shut off. Mack says her family was evicted 17 times as they cycled through apartment complexes in Norcross, Georgia. Sometimes there was a notice every month stating that if they did not pay up in 10 days they would be kicked out.

Meghan Kallman grew up in Harrisville, New Hampshire, a mill town that she describes as being like a smaller version of Pawtucket, which she now represents. Her family was large and she began working at 14, earning $5.15 an hour to work the counter and coffee bar at Fiddleheads Cafe and help with cleaning and dishes.

“I do not believe an Excel sheet should tell you whether or not you should raise the minimum wage.”—DAVID MORALES ’19 MPA

Jonathon Acosta feels like he “won this lottery ticket” by being born in America. Some members of his family—like his mother, who is originally from Colombia—were not and he watched as they struggled with the U.S. immigration and citizenship process. His mother also emphasized the importance of a good education. But he doesn’t want to be the poster child for any narrative about self-determination. “Usually we tell this rosy story about pulling yourself up by the bootstraps, but I think it’s bullshit,” he says. “I think I got very lucky.”

Academic freedom + a public-service mindset

Mack always knew she wanted to go to Brown. Her third grade teacher asked her, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

In response, Mack wrote: “A Brown student!” For her, Brown meant academic freedom, self discovery, and no constricting rules.

As a sophomore at Brown, she began teaching sex ed in Providence schools through the Swearer Center. Coming from the evangelical south, where “sex was a bad word,” she was amazed at the students’ comfort with their sexuality. With no embarrassment, they would ask her questions like “How can you put on a condom?”

At Brown, Morales was much younger than the other students in the MPA program, who were mostly in their late 20s. After class, they would troop over to the Grad Center bar. He was never old enough to go. But he liked Brown’s public policy focus and the program’s social advocacy track. While he already had activism experience, Brown taught him about the policy structures that facilitate change.

He says, “I wanted to pursue a master’s in public policy that centered around social change as opposed to being quantitative focused, because I do not believe an Excel sheet should tell you whether or not you should raise the minimum wage.”

Acosta wasn’t sure he wanted to go to Brown, but his uncle recommended applying and told him about then–President Ruth Simmons. He says being around her was like being “in the room with a superstar.” But he recalls it being a difficult adjustment. There weren’t a lot of people who looked like him, he says.

He has come to love the University. Currently, he is working on his fourth Brown degree, a sociology PhD. And he has a tattoo of the sun and scroll from the Brown University seal on his upper right arm.

For her first year in the Brown PhD program, Kallman lived on the East Side. But she soon discovered Pawtucket and loved it, in part because of its resemblance to Harrisville.

Later, she began teaching sociology and globalization courses in the Rhode Island prison system, which was challenging because her students did not have access to computers or a library for research. So she used course packets, had them do a lot of writing, and invited Brown peers and mentors to speak.

“We tell this story about pulling yourself up by the bootstraps, but I think it's bullshit. I think I got very lucky.”—JONATHON ACOSTA ’11, ’16 AM, ’16 AM

Her teaching ties into her political work. “The most useful skills I have in being a politician and an organizer were developed as a teacher, including: playing the long game, being comfortable with profound disagreement and managing productive interaction despite it, speaking publicly, reading policy carefully, and paying attention to both the spoken and unspoken communication.”

The “politics as usual” that made them run for office

All were inspired to run by disillusionment with the Rhode Island political status quo. Morales can’t remember the exact moment when he decided to run. But he does remember testifying at state committee hearings. In one, advocating for a $15 minimum wage, he recalls talking about the local economic benefits of raising it and also about his mother and his childhood. Then the bill was “held for further study.”

He asked one of the sponsors, “What does this mean? What’s going to happen now?” She replied, “Oh, that’s kind of it for the year. That was the one hearing we had and even though it has not formally died, the bill’s not going to move forward.”

“That hypocrisy,” he says, and “the fact that not a lot of change happens in the state of Rhode Island” inspired him to run.

During the fight to pass the Reproductive Privacy Act, which codified Roe v. Wade into state law, Mack sent a letter to Senator Harold Metts asking him to support it. “He wrote back three Bible quotes,” she recalls, “and basically said he answers to God, not man.”

After the act was finally passed, she says Jennifer Rourke, a Rhode Island political activist, told her she should run against Metts. Mack said, “Oh, I can do that?” She thought politicians had to have studied public policy or had law careers. But she realized “that wasn’t the case—and I feel so significantly more qualified than most people who are in that building.”

Ultimately she toppled Metts, who was first elected to the legislature as a representative in 1984.

Acosta also decided to run after becoming disillusioned with his district’s state senator, Elizabeth Crowley. First he disagreed with her on education. He thought there were ways to improve funding for Central Falls schools. But, he says, she “was just not about it. We would have demonstrations and she wouldn’t show up. They would cut our funding and she would be quiet.” Then, he says, she didn’t do anything to protest the use of Wyatt Detention Center to house ICE detainees.

Later, Acosta says, his partner, who was pregnant with their first son, testified in favor of the Reproductive Privacy Act. He sent Crowley an email asking her to pass it. He claims she told him that as long as the bill was within the bounds of Roe v. Wade, she would vote for it. But when the floor vote came she voted against it.

That was strike three. As he talked to voters, he realized that some people in the district didn’t even know that Crowley was their state senator. Acosta says he is the first Latino to represent Central Falls, a city that is primarily Latinx.

As Kallman campaigned over the summer, knocking on doors in Pawtucket, she found that residents, who had been cooped up for months, were eager to talk. She especially remembers discussing COVID with nurses, who told her that they had been forced to work without PPE or with reused equipment.

Kallman thinks residents knew she would work for their interests. In June, while she was still a member of the Pawtucket City Council, she was the only one to vote against a new police contract.

Where they want to take RI—and how it’s going

Tiara Mack says she wants to live in a fantasy world like the one in the novels she reads. That world would have equitable schools with “teachers who look like the students,” clean energy, community gardens, buses so one could get to the grocery store or health clinic within 15 minutes, 20-hour work weeks so people could participate in politics. There would be no homelessness or food insecurity.

Will we ever get there?

“That is my mission. I want to retire at 40!” says Mack, who is 27. But so many obstacles remain.

“The most useful skills I have in being a politician and an organizer were developed as a teacher.”—MEGHAN KALLMAN ’16 PhD

One of Kallman’s major issues is criminal justice reform. She wants to rethink the women’s prison. “Most of them are serving very short sentences and it’s a very inefficient use of our money,” she says. Along with Mack and Acosta, she sponsored a bill, Senate Resolution 245, to create a commission to examine different solutions for reducing female incarceration.

In March, 2021, the Senate Judiciary Committee recommended that the bill “be held for further study.” Mack believed it could still succeed if they do more work on the bill, but she conceded, “Typically, 90 percent of the time, bills do die after they’re being ‘held for further study’ if the right work is not done on them after that.”

In June, the bill passed.

Now that Morales is in office, he has ambitious goals for his first term. He wants an eviction moratorium and rent relief for small businesses. He would like to put a $25 monthly out-of-pocket cap on insulin and to cap all out-of-pocket expenses on a monthly basis for specialty drugs. After a months-long process, the insulin bill passed the House and Senate and was signed into law in July, albeit with a $40 ceiling. He also sponsored another successful medical bill, introduced by Acosta and Kallman in the Senate, that prevents insurance companies from charging copayments for COVID-19 treatment and vaccination.

Morales is wading into a battle to change Rhode Island taxes, too. He thinks the wealthy should pay the 9.99 percent tax rate they did before 2006. And he wants to tax large nonprofits like Brown and RISD, which he feels shift the tax burden to middle and working class families as they gobble up property.

Morales initially wanted to post notes on his website for all the official meetings he attends. “Everyone should be involved and engaged and understand what their government is doing with their tax dollars,” he argues. Yet he hasn’t added any since mid-January 2021. Without full-time staff and with a busy session, he says he didn’t have time, but interns are now working on updating the page.

Acosta is passionate about these issues too, but in his sociology research he has studied charismatic leaders and thinks it’s dangerous to focus on personality rather than policy: “I’m not concerned about being the poster child and the top sponsor for any of this stuff. I just want to make sure that it gets done.”

Later, he adds, “I think we candidates, at least for me, are all interchangeable. What matters is, are we committed to being the champions of this agenda?”

In their first year, they have seen successes and disappointments and have often worked together on bills. Kallman is proud of a bill that she sponsored with Acosta and Mack to raise real estate transfer taxes on expensive properties and earmark the marginal yield for affordable housing. She also sponsored legislation with Acosta and Mack in the Senate and Morales in the House, signed into law in April, that prohibits discrimination by landlords against people’s legal sources of income and a bill, signed into law in July, that banned landlords from not renting to tenants because of their sexual orientation.

The Whistleblowers’ Protection Act

is another signature bill. Kallman, Acosta, and Mack were Senate sponsors and Morales was a sponsor in the House. It strengthens whistleblower rights and forbids employers from reporting an employee’s immigration status to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement or police. It was enacted in July.

“I don’t want to be a progressive. I want to be someone who is focused on getting good people-centered policy for everyone.”—TIARA MACK ’16

Another bill signed into law, which prevents discrimination against people with disabilities who need organ donations, was especially personal for Acosta—he has a cousin with Down Syndrome. He also sponsored a bill to provide body cameras for all Rhode Island police departments, which passed with nearly unanimous bipartisan support.

But Acosta concedes he has not yet accomplished everything that he had hoped to. A bill to provide undocumented immigrants with driver’s licenses hasn’t worked out, and neither has a bill sponsored with Mack and Kallman to raise taxes on high earners, or another bill that would move towards legalizing recreational marijuana.

For him, it’s been a “glass half full, glass half empty” experience. He says, “I feel like the biggest thing I’ve probably taken away is that a lot of the devil is in the details and I would encourage people to spend more time [in the minutiae of government]. I feel like we get really caught up in the big ideas and those are the things that are sexy, frankly, but the details matter a lot, too.”

As Mack sits in front of a stylized picture of a Black woman covered with the names of famous Black women: Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell; a portrait she painted of her rabbit, Moonlight Mahershala Black Excellence; and a rainbow she crocheted herself; she speaks earnestly about the things she wants to accomplish.

When Mack starts talking about an idea she finds interesting, she can keep going for nearly ten minutes without pausing. You get the sense that you’re at a protest or a march. Several times, she apologizes for “ranting.” But her passion is contagious.

Like the other three, she wants tax increases for the wealthy, a Rhode Island Green New Deal, healthcare for all, and better housing. Her push for a $15 minimum wage was signed into law in May and will take effect in 2025. These are things she won’t compromise on, but she says she wants to work with her colleagues, even if they don’t agree.

Now that she’s in office, it’s “annoying and still surreal” to be in the public gaze, but she tries to be authentic. “I still have yellow hair. I need a haircut, but I’ve got stuff going on,” she says. “And I still flip up and say ‘fuck’ all the time.”

Mack has been attacked for what some see as a radical militancy. After she posed for a photo on the State House steps with two other progressive freshman legislators, political commentator Gene Valicenti spoke disapprovingly of Mack: “She unseated Harold Metts and she’s coming in with an agenda. Have you seen that picture she posted? Very fierce-looking. Is she coming up here to fight with you? What would you say to her? You going to explain politics, how it works? This is a young person, who has her own idea about things.”

He later apologized and hosted Mack and the other women on his show.

Joe Shekarchi, Speaker of the Rhode Island House, was also on that program and suggested the legislature would make the young women more moderate.

Mack doesn’t think so. She says, “in some respects I will have to change, but I hope it’s not in the traditional sense of like, ‘Everyone when they get into office becomes more moderate!’ No. Fuck that.”

Despite their new political ascendancy and their left-of-center goals, these four young politicians don’t want to be branded as progressives or radicals. They see themselves as largely policy focused, not ideology or personality focused.

“I don’t want to be a progressive,” Mack says. “I want to be someone who is focused on getting good people-centered policy for everyone.”

Noble Brigham ’24 has written for publications including the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Providence Journal.