Archiving the African Diaspora

Anani Dzidzienyo’s presence was healing; his scholarship, groundbreaking. You could say the same about the class created in his memory.

Though he had no kids of his own, Professor Anani Dzidzienyo’s legacy lies undoubtedly in his children.

“He had a lot of adopted children, that’s the way I put it,” says Martin Obeng, a decades-long friend of Dzidzienyo’s who teaches African drumming at Brown. “A lot of unofficially adopted children, all over the world.”

Dzidzienyo was born and raised in Ghana, arriving in the U.S. to attend Williams College in 1965, and became a pioneer in Afro-Brazilian studies. His scholarship is fundamental to the contemporary study of the African diaspora in Latin America, and fellow researchers credit him with being among the first to coin the term “Afro-

Latin” in English.

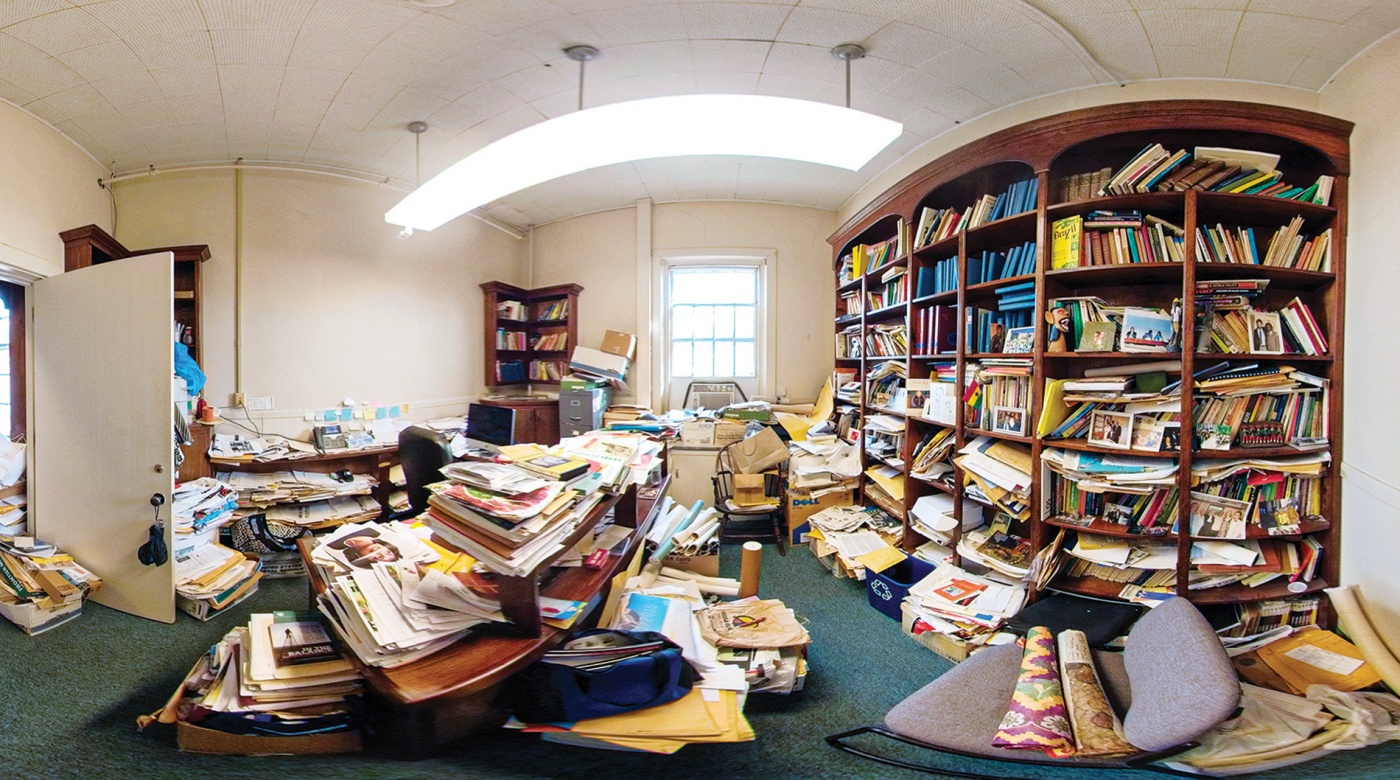

In October 2020, midway through his 47th year at Brown, Dzidzienyo died of cancer, leaving behind a two-room office on Angell Street overflowing with history. Rather than leave the countless books, photos, papers, and costumes to the librarians and cleaning crew, the life and times of Anani Dzidzienyo have been placed in the hands of the students he aimed to serve, by way of a once-in-a-lifetime course on archiving his materials.

“This class came about in the absolute midst of grief,” explains Keisha-Khan Perry, the instructor for AFRI 1941, who worked alongside Dzidzienyo for 15 years. The two bonded over a shared knowledge of Portuguese and a mutual fascination with the Latin American side of the diaspora. “I knew I wanted to preserve his materials and saw this as an opportunity for the next generation of scholars to continue his work,” adds Perry, “but a lot of the course came about organically, based on a really gifted, committed group of students.”

Churchhill House is ground zero for the hybrid course, which consists primarily of sorting through the records compiled by Dzidzienyo during his decades at Brown— determining what to keep in the University collection and what to give away to other universities, prison libraries, and other public wells of information. A walking archive himself, Dzidzienyo kept everything he received from nearly every one of his students, from old Polaroids to first drafts of final papers.

“You’re sucked into another world, because there are thousands of books and thousands of papers,” says Youma Traore ’21, one of the students in the course, who was also part of Dzidzienyo’s final class of students last fall. “We’ve been working for months and haven’t even touched a twelfth of what he has. Most of the books are about Brazil, but it’s interesting going through them because so many are written by his former students. It’s just amazing to see the impact that he had, where so many people came to Brown wanting to be his student, and then became scholars in Afro-Brazilian studies, following in his path.”

The other key component of the course is lecture. Friends and students of Dzidzienyo are invited to speak about their memories of him and his impact on their life. The discussions are recorded as a form of oral history and will become part of the overall archive. Students are also conducting additional interviews with everyone from University shuttle drivers to custodians to demonstrate the breadth and depth of Dzidzienyo’s relationship to Brown’s campus.

“One of the incredible things about Anani is that he would meet you and bring you into his orbit, but he didn’t turn you into him,” says Jeffrey Lesser ’82, ’84 AM, one of the course’s guest speakers. “He somehow found what you didn’t even know about yourself, and brought it to the forefront.” Now the director of Emory University’s Halle Institute for Global Research, Lesser is a specialist in Brazilian Studies and modern Latin American history whose career began in Dzidzienyo’s classroom—or in those days, at his dinner table.

Lesser vividly recalls evenings spent in the dining room of Dzidzienyo’s house on Charlesfield Street, sitting alongside his fellow students as his “mind was blown open.” One of Dzidzienyo’s greatest gifts, Lesser says, was his ability to build lasting personal relationships with his students. Lesser doesn’t hesitate to call Dzidzienyo a father, remembering one Passover when his professor drove back home with him to spend the holiday with Lesser’s “crazy” family. That family is one of several whose ties to the professor were multigenerational: Dzidzienyo also served as the first-year advisor to Lesser’s nephew and both of his sons.

Kunovenu Haimbodi ’22, TA for the course, describes the office as “a truly sacred space within this university for a lot of folks who didn’t find homes or communities elsewhere.” Haimbodi, who scrapped any thought of becoming an engineer after a single class with Dzidzienyo freshman year, is designing an immersive 3D virtual rendering of the office and has applied for a fellowship to continue the archival process alongside University staff. This pursuit will dovetail with an extensive research project Haimbodi is conducting in partnership with students in Brazil about the African diaspora. The research wouldn’t be possible, Haimbodi explains, were it not for his rapidly expanding knowledge of Portuguese, which he began studying after encouragement from Professor Dzidzienyo.

“This man was like, ‘You have to learn Portuguese to engage not just with care but with rigor,’” Haimbodi remembers. “And it’s not being rigorous for the sake of a good grade, but because that’s the only way you’re going to be able to engage with communities that aren’t your own.” This advice, he says, was one of the most profound lessons he learned from Dzidzienyo, and one of the most important to preserve. And though many tangible relics of Dzidzienyo’s life will make their own diasporic journey from his office around the world, his spirit echoes in hundreds of students who will retain and repeat his wisdom for generations to come.

This intellectual and human generosity was inspiring, Lesser says. “I’m not a good enough person or a good enough scholar, but I try to be like Anani, and I’ve thought about it for many years: how Anani changed me and continues to change me. If I could be like that for my students, even a little tiny bit, I could be proud of my own career.”