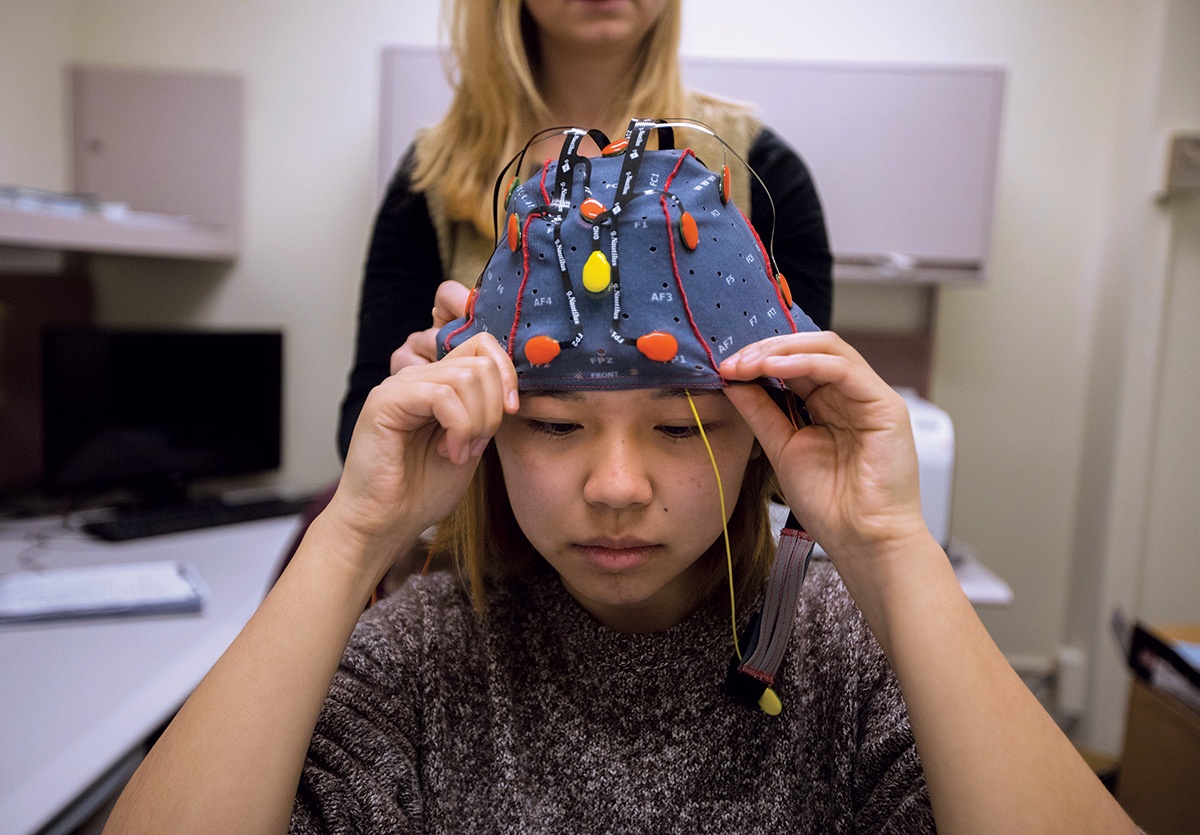

The Science of Silence

Meditation and mindfulness meet neuroscience in a young academic concentration.

Hiroe Hu ’13 came to Brown to study chemical engineering, and she was stressed. “I started thinking about what it means to be human; why people fall ill and suffer.”

She began talking to Professor of Religious Studies and East Asian Studies Harold Roth, who since 2000 has been introducing students to Buddhist meditation. Since 2005, Roth has headed up Brown’s initiative in contemplative studies (CS), which teaches the history, culture, and neuroscience behind meditative practices. It became an official concentration in 2014.

When Hu took Roth’s class Introduction to Contemplative Studies, “I loved it,” she says. “It was ironic because I had grown up in Japan surrounded by these Zen cultures and not paying attention to them.” Hu, now a medical student at Touro University in Vallejo, California, concentrated both in chemical engineering and CS, which she credits with “giving me the navigation tools to deal with the human psyche. My goal now is to become a psychiatrist, and I have a special interest in looking at the connection between the mind and the body.”

MEDITATION AND CANCER

CS concentrator Chloe Zimmerman ’15 MD ’22 worked in professor Catherine Kerr’s contemplative neuroscience lab to help design a clinical trial examining how Qigong, a movement and meditation practice, affects cancer patients. Since Kerr’s death in 2016, Zimmerman has continued the work as project manager in Associate Professor of Neuroscience Stephanie Jones’s lab, where she also tests whether mindfulness can prevent burnout in medical students.

Zimmerman, who uses neuroimaging and immune analysis, says she’s learned her humanities background helps her better interpret data. “Having that background in Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism is just as critical as the MRI and statistics courses I took,” she says.

A BALANCE OF DISCIPLINES

The CS program was an interdepartmental independent concentration before becaming a full-blown program. It has graduated 30 concentrators, many of them premed students or scientists looking to balance empirical data with a different sort of knowing.

Roth describes the program as “radically multidisciplinary,” with an equal balance of science and humanities course requirements. “To go across major divisions of the University between science and the humanities,” he says, “is something that’s really rare.”

Even more unusual is an aspect Roth and his colleagues call a “critical first-person” inquiry. That means CS students learn to meditate. “If we study the ideas that these texts talk about without studying the practices, we’re missing half the equation,” Roth explains. “It’s like the difference between reading about baking a soufflé and actually baking the soufflé. It’s important for students to say, ‘Hey, I tried this out, and it wasn’t working. Why is that?’” With the popularity of mindfulness exploding in popular culture and business, Roth feels it’s essential that academics take a deep and critical look at the sometimes overblown claims of meditation as a cure-all.

The CS program takes an evidence-based approach, with Eastern practices meeting Western science. “We balance some of the more traditional religious studies like Hinduism, Sufism, Taoism, and Christian mysticism with this emerging scientific discipline exploring what’s really going on in the mind on a neurological level when we meditate,” says Srinivas Reddy ’98, a visiting professor in the program. Recent research has linked meditation to such things as lower blood pressure, reduced stress, and a decrease in PTSD symptoms. “Students start to develop their own contemplative practice,” Roth says, which, science has suggested, can offer sharper focus and improved emotional resilience. That’s definitely the case for Carly Margolis ’16, now the program manager of the Mind and Life Institute in Charlottesville, Virginia. “I came out of Brown with a really high level of self-awareness,” she says.

A HARD SELL

Brown was the first higher education institution to offer contemplative studies as a concentration, though the field is represented at such campuses as Syracuse, Rice, the University of Virginia, and Rutgers. Getting buy-in from the Brown administration was challenging, at first, Roth admits. “But because what we do has been grounded in important, solid, scientific research and we’ve developed a rigorous system of courses,” he says, “little by little, skeptics have been won over.”